Gravity's Rainbow - Part 3 - Chapter 5.2: The Synthesis Committees

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 3 - Chapter 5.2: Oneirine and Methoneirine, Tchitcherine's Father in Südwest, the New Turkic Alphabet Committee, the Atjys and the Kirghiz Light

Tchitcherine (Still) in Kyrgyzstan

Tchitcherine saw a number of opiate derivative variations in Wimpe’s collection. Two specific ones, Oneirine and Methoneirine, were even created by Laszlo Jamf, the man who conducted his experiments on young Tyrone Slothrop. These two drugs were explorations into the possibilities that may lay dormant in the common morphine molecule, itself an opiate derivative. This exploration was being pushed by DuPont, the infamous chemical manufacturer responsible for a number of deadly plastics and which, within the novel, eventually possibly merged with Grössli Chemical Corporation, creating a cover company via a deal with IG Farben known as IG Chemie, and finally coming to be known as Psychochemie AG (2.7). No surprise that the same chain of companies and manufacturers that produced poisonous plastics and substances such as Imipolex G also have been delving into the world of pharmaceuticals. Oneirine and Methonerine specifically were created in hopes “to find something that can kill intense pain without causing addiction” (348). Unfortunately, a person’s desire for pure analgesia — the negation of pain — inevitably leads to addiction.

Wimpe elaborates to Tchitcherine on the desire to find a drug as such. The desire to eradicate pain without addiction is put in terms of surplus cost, an allusion to Marx’s Theory of Surplus Value, not because Wimpe or any salesmen like him care an ounce for Marx — not to mention that they likely detest every word that has ever come out of his mouth or pen — but because putting things in terms such as these, terms that appeal to the working class person who is likely to want to use such a substance, would help “soothe the customer” (348). But why would They want to help the proletariat suppress their own pain?

We know how to produce real pain. Wars, obviously . . . machines in the factories, industrial accidents, automobiles built to be unsafe, poisons in food, water, and even air—these are quantities tied directly to the economy. We know them, and we can control them.

(348-349)

The ability to participate in these activities such as war, production, and transportation, creates a profit that They can reap. If They could simultaneously provide us with a substance that removes the most undesirable facet of these activities, the pain associated with them, then not only would They profit on our continuance in participation (and likely the increased participation for lack of fear), but also on the purchase of the product that takes away the pain which we then would know provides no negative side effects such as addiction. This would give Them a “direct conversion between pain and gold” (349). And though Tchitcherine criticizes Wimpe and his kind for “‘trafficking in pain,’” Wimpe, evil though he is, makes a good point: “‘Doctors traffick in pain and no one would dream of criticizing their noble calling’” (349). Perhaps these dealers of product, whether they lay within the realm of pharmacy, plastics, weaponry, or any other realm, are not the only ones pushing the world further into hell.

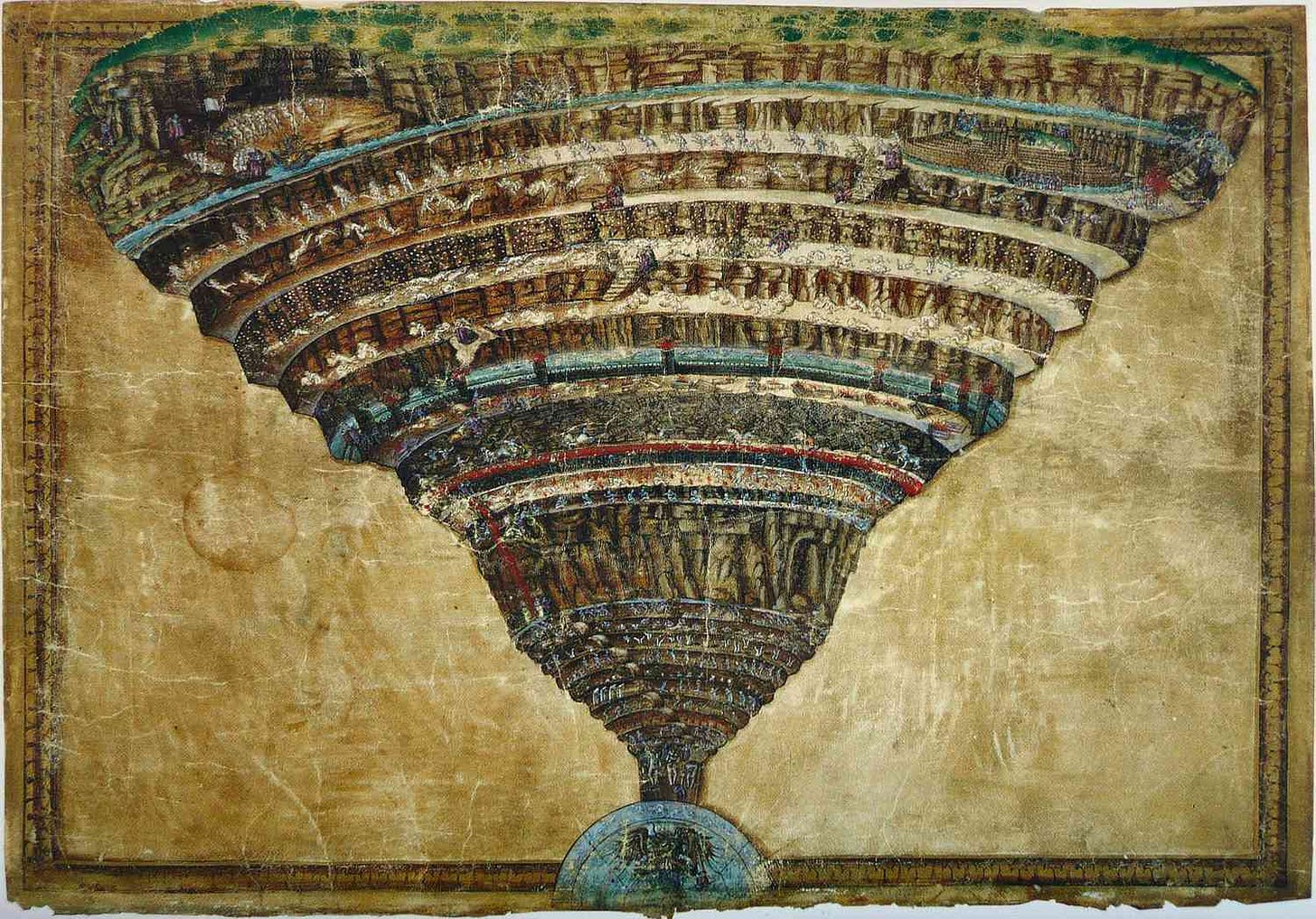

But as for the characters, Wimpe was reassigned to some other company in the US — which would not be stretching to assume is connected with the various others mentioned in previous chapters — and Tchitcherine, well, there still isn’t proof enough to verify that he ever even met the man. So, he only has paranoid theories as to why he has been exiled here — another connection to Slothrop. He believes it must be because of Enzian. For, he has delved into dense pre-Soviet-revolutionary materials and found bits of his family history; he has pondered the ideas of being exiled for seeing a mistress that only They wanted to touch and for meeting a supposed dope salesman. And yes, They, like Dante’s vision of Hell, would be the ones to seek some form of absurd retribution. But nothing seems to provide a real sufficient reason, for this is no longer occurring in the real war time; it is a time between the wars — a time where something such as this should not occur so readily. In the materials that he searches through, he first read his father’s history, which led to this belief that Enzian was the reason for his exile.

Tchitcherine’s Father

As we learned of Slothrop’s family history, so too do we get a small taste of Tchitcherine’s (Jr.) via the materials he scours through. His father, also named Tchitcherine (Sr.), was on board the ship of fleet commander Admiral Rozhdestvenski during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. The ship stopped in Lüderitzbucht, a bay on the coast of Namibia in Südwest Africa, home to the Herero, “trying to take on coal” (350) — notice the Germanic name in the Southwest African country. The Russians plundered the town for its coal, calling to mind the base form of the substance that would soon be used to synthesize the plastics, drugs, and weaponry later in the 20th-century. So, Tchitcherine (Sr.) is both a literal and thematic precursor to Tchitcherine (Jr.), being the man of flesh as opposed to the man of steel, the searcher for coal as opposed to the searcher for what was synthesized out of coal. And while here, Tchitcherine (Sr.) found a Herero woman who had recently “lost her husband in the uprising against the Germans” (350) during the earliest stages in the Herero genocide of which Weissmann would become a part of in its later stages. This is where they will all be tied together.

Back in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Tchitcherine (Sr.) already “had a wife […] and a child hardly able to roll over” (350), the child being Tchitcherine (Jr.). But Tchitcherine (Sr.) was unable to cope with the perversion of blackness that was occurring in this world of coal. He could only think of each of these men being covered in the soot and coal dust, transforming their skin into pure carbon — the quintessence of power. The artificiality of it terrified him, reminded him of Death — was death, in a way. The coal one day would pollute the air and be synthesized into further means to kill, yet here it was, already showing in its basest form the type of death it would enact, clinging to the skin of each man, polluting their lungs, crystalizing in their sweat. So, he went ashore to find “the honest blackness of the solemn Herero girl” (351). They lived simply for the short time he was there, in their brief respite from the hell that revolved around both of their lives. It was here that Enzian was conceived, making him, as we’ve heard, Tchitcherine’s (Jr.) younger half-brother. Despite the hatred that they both hold for each other — even having never met — Enzian was not born out of hatred itself. He was born out of a spat of intense love and even respect. For before Tchitcherine (Sr.) left, he and Enzian’s mother “had learned each other’s names and a few words in the respective languages—afraid, happy, sleep, love . . . the beginnings of a new tongue, a pidgin which they were perhaps the only two speakers of in the world” (351).

But he did leave. He had to. And he did not survive the journey home either. As we learned of in Enzian’s early life history, his mother gave birth to him and passed away, leaving him in the Kakau Veld to be raised by the Ovatjimba, the poorest of the Hereros, before he was returned to his home village (3.3) where he would eventually become the slave of Weissmann (1.14).

Tchitcherine at the New Turkic Alphabet Committee

So, it is through the discovery of all these documents regarding his father and his half-brother that Tchitcherine comes to the conclusion that this is why he was exiled. For, after discovering these documents, he also discovered that Enzian came to and applied for citizenship in Germany in 1926 (perhaps to find Weissmann or perhaps as the beginning of his idea of revenge). But either way, Enzian’s dossier was “stashed in Thitcherine’s own dossier” (352) which led to him being sent to a session of the VTsK NTA (the All-Union Central Committee on the New Turkic Alphabet) which took place in Baku, Azerbaijan.

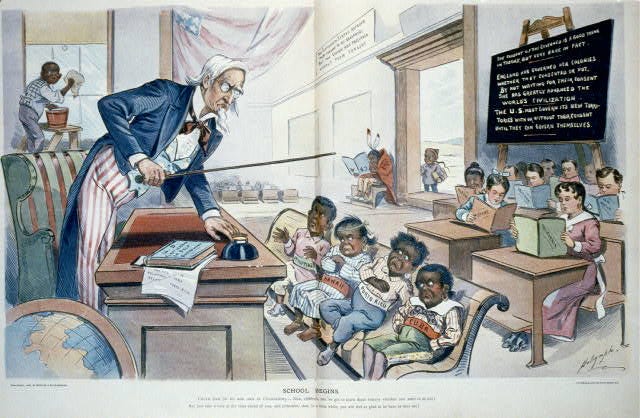

It is here at the NTA Committee that the actual New Turkic Alphabet is fully conceived, the same which would eventually be spread to those tribes in Kyrgyzstan. We learn of some of the letters, entirely new sounds that Tchitcherine and many on the committee could not distinguish from letters within their own languages, which should already call to mind the impossibility of developing an alphabet for a language you cannot even hear correctly and then giving this alphabet to a group who have never used an alphabet at all. The Committee represents the people in power, synthesizing a new form of language/substance which will be used to control an oppressed group. They fight over which letter (molecule/atom) will be used to replace or stand in for the letter (molecule/atom) in the newly synthesized word (substance). And to them, this debate and new synthesis is all fun and games — pranks and gags run abound as the “pencils in [the] conference room […] mysteriously vanish” and “pieces of chair leg all around the table [are] sawed off” causing “bureaucrats [to] go toppling over on their ass” (353). And it really is all fun and games for them, for they are simply the creators of the new language similar to the scientists who simply followed orders to synthesize a new substance just like Franz Pökler or Roland Feldspath. No, these creators are not relieved of blame, but they certainly aren’t the same as the ones who led them to create and who enacted that new creation’s distribution.

After a battle between Tchitcherine and Blobadjian (his enemy at the committee), the NTA is decided to be modeled on the Latin Alphabet, for as they discuss, every other alphabet just has one too many oddities about it. But quite obviously, these oddities are only odd to the distributors of said alphabet, and we know that They need the Latinization or Westernization of the entire world, not the Arabization or Russification of it. “But the Arabists aren’t giving up,” for the Turkic/Kirghiz people who this alphabet will be spread to “are, after all, Islamic, and Arabic script is the script of Islam” (354). Every aspect of these peoples’ lives is going to be Latinized, from their thought to their own religion.

Blobadjian is chased out of the committee by a group of these Arabists who are angry with him over the decision. Through his chase, we see the abandoned flanks of oil towers and refineries. This land, in Baku, was a place where Dutch Shell had plundered, extracted its oil from the earth, and left the country hollow — just another stopping point in Their journey to appropriate all of the Earth’s resources, leaving the people worse off because of it, in order to synthesize their own climb toward higher and higher thrones.

But Blobadjian is saved from dying an infidel and instead learns how to alter his own molecular structure to spiritually perceive the connection between language and the nature of molecules.1 He alters his index of refraction and realizes that the Committee on the NTA is just the same as the many “Committees on molecular structure” — how molecules and words can be “modulated, broken, recoupled, redefined, co-polymerized” (355). New syntheses of words are like new syntheses of molecules. So, something as trivial as the voiced uvular plosive G of the common Turkic alphabet compared to the standard Latin G is not significant as the members of the committee thought it to be. For these letters, these atoms, already existed. It is their manipulation, combination and recombination, and how they synthesize new structures to find their way toward an entirely new means of control. It is no wonder each and every member of the NTA Committee, or each scientist working on these molecular/weapon-based syntheses, were split up into isolated groups. It is because They are the only ones who wanted to be able to see these end goals; It is They who are orchestrating the clockwork going on below while people die; it is They who manipulate the means of control while their little underlings, like Tchitcherine and Blobadjian in the NTA Committee or Franz Pökler and Roland Feldspath in the construction of WWII weaponry, did their unknown bidding, shuffled off to a corner to solve their own insular, seemingly unconnected, problem.

Tchitcherine (Yet Still) in Kyrgyzstan

Džaqyp Qulan and Tchitcherine arrive at “the village they’ve been looking for” (356). As they enter, they come upon what is known as an ajtys: a singing-duel in which two contenders would free-style (genuinely similar to a modern rap free-style though with different content) a series of lyrics sung toward each other, usually accompanied by traditional instruments such as the qobyz and the dombra. The lines that are sung, again, like a modern free-style rap battle, contain witty jokes, insults toward the opposer, and invoke laughs and cheers from the audience — even evoke anger from they who are insulted. These battles stem from the oral traditions of the people who sang them — spoke them. The traditions could be these battles similar to modern free-styles or memorized epic poems such as those that Homer traveled and orated to groups — not as a linear story from the wronging of Chryses and Chryseis to the mourning and funeral of Hector, but a memory of a fragment of a story, one that the audience begs for and which the poet, the artist, lets flow free from their mind and their mouth, changing and reciting things as they see fit for the moment, always allowing whatever spiritual or human messages rise from their core to mix in with what they knew before — adjusting, changing, for the new moment before them. Tchitcherine knows that these free verse lyrics will one day, with the New Turkic Alphabet that he helped create, be written down, memorized word-for-word, performed identically each time — the same melody flowing recognizably over them, the same rhythm, as well — and that “this is how they will be lost” (357). The human nature, the spirit held within them, will be reduced to mere heartless reproductions of their original self.

When the atjys morphs from something insulting and witty to something kind and loving, Tchitcherine and Qulan sit beside the Aqyn — a Kirghiz bard possibly similar to one in the position as Homer was — who sings his song while Tchitcherine will write it down. The song speaks in awe, referencing a sight that even the greatest of aqyn could not describe in their words: the Kirghiz Light. This light calls to mind other-worldly phenomena at first — the aurora borealis or things of the sort. Yet, the aqyn’s song goes on telling of “The roar of Its voice” and “The flash of its light” (358). This light is other-worldly, but is somewhere “Where even Allah cannot reach” (358) — a feat that is beyond what God had intended. Perhaps it is the blinding light after the flash of a bomb or rocket test, or just a natural feature of the world such as the northern lights. But either way, if one were to see this light in a world where Homer’s natural poetry reigned, where the atjys held superiority over the recorded or written down song, where oral tradition stood atop of the written word, and where the community surpassed the importance of the individual, then “a man [could] not be the same” (358).

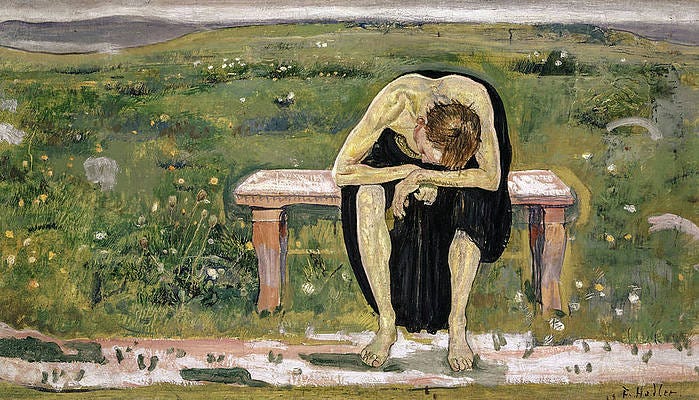

We are not in that world any longer. All that Tchitcherine got from the aqyn’s song was the directions to the Light: “It is north, for a six-day ride, / Through the steep and death-gray canyons . . .” (358). He says that he understands, but does he? So he and Qulan set out to find the Light. And find it they do. Yet, Tchitcherine, poisoned by the modern world of synthesized language, himself built of metals only possible in the mechanized world that we live in, spent twelve hours staring at this light, not feeling a thing. If it is the natural phenomena such as the aurora borealis that he saw, then his inability to sit with the natural word did not allow him to find awe in the most awesome of sights. If it was the horror of the light of the bomb, then it shows his desensitization toward the most horrific phenomena created by man. And. . .

And . . . Back In the Zone

. . . back In the Zone, he is once again attracted to a light. But this time, a less natural light. He seeks the Rocket. The same 00000 V-2 that Slothrop, Enzian, and Marvy seek. He is drawn to it in the hope to destroy it.2

Up Next: Part 3, Chapter 6

This final scene with Blobadjian is very complex, odd, and unclear. If anyone has a better/different reading on it than I do, I’d love to hear about it in the comments.

A brief note on the chronology of this chapter:

Non-chronologically is how we learn of these events:

1: Tchitcherine In the Zone, searching for the Schwarzgerät, Enzian, and Slothrop

2: Tchitcherine in Kyrgyzstan spreading the NTA with Qulan and the others

3: His musings on his affair with the courtesan and his meetings with Wimpe

4: The discovery of the documents which told the story of his father’s and Enzian’s past

5: The actual account of Tchitcherine’s father on the Admiral’s ship, the conception of Enzian, and the birth of Enzian

6: The NTA Committee in Baku and its associated shenanigans

7: The final scene in Kyrgyzstan with Qulan, the atjys, the aqyn, and the Kirghiz Light

8: Back to the Zone

Chronologically these events happen as follows:

5: Tchitcherine’s father on the Admiral’s ship, the conception of Enzian, and the birth of Enzian

3: Tchitcherine’s affair with the courtesan and his meetings with Wimpe

4: The discovery of the documents which told the story of his father and Enzian

6: The NTA Committee in Baku and its associated shenanigans

2: Tchitcherine in Kyrgyzstan with Qulan and the others

7: The final scene in Kyrgyzstan with the Kirghiz light

1 & 8: Tchitcherine in the Zone, searching for the Schwarzgerät, Enzian, and Slothrop

Mistakenly posted these notes on the last article, belong here.

I like how Tchitcherine's relationship with Wimpe is stubbornly hypothetical...

Noticed that Wimpe (remembered by Tchitcherine *if* the two had ever met) talks about Carothers of DuPont, the chemist who invented nylon, so that is referenced directly (at least) twice in the book. The parallel between drugs and plastics P. draws here is really interesting and compelling to me. https://substack.com/home/post/p-125387318

Wimpe works for IG Farben: "Our little chemical cartel is the model for the very structure of nations"

Kirghiz Light, all references in the book: https://gravitys-rainbow.pynchonwiki.com/wiki/index.php?title=The_Kirghiz_Light

This article for the Aqyn's song: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1347396 <- I need the PDF if anyone has JSTOR

Dzambul: http://www.cyberussr.com/rus/dzhambul.html

Qoryt: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Dede_Korkut

-> context: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bagshy