Gravity's Rainbow - Part 3 - Chapter 11.2: Switching Tracks

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 3 - Chapter 11.2: Ilse's First Visit, Visions of the Moon, Kekulé's Dream, the Benzene Ring, Pökler and Weissmann, Ilse's Second Visit, to the Zwölfkinder

Franz Pökler’s Ilse has returned — not to the Wheel which he waits under in the present, but to Peenemünde where he and many others are engineering the V-2. He stepped into his cubicle after another day of questioning his purpose on this job, and what better symbol to restore his hope in the project than the symbol of all that he loved, missed, and fought for. She was waiting here at just the right moment. This coincidence does not fall on an unsuspicious mind, for one of the first things Pökler thinks after lifting her and kissing her is, "Was it really the same face?" (407). The suspicion grows as it turns out that she was brought here by Weissmann/Blicero himself,1 and Pökler, losing all belief in the privacy he believed he had, sets to questioning Ilse.

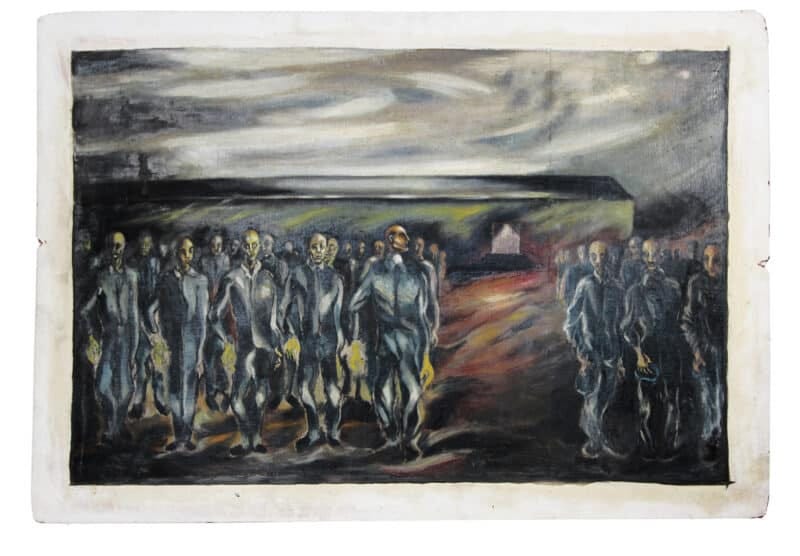

She was sent here from a concentration camp, though based on the time, Pökler wouldn’t have immediately known what it was: a place "surrounded by barbed wire and bright hooded lights that burned all night long," where "old ladies [lived] in barracks, stacked up in bunks" (408). She was here with Leni who was taken away every so often by a man in uniform, used for some unknown purpose of which she would not speak when she returned. Pökler’s optimistic thought is that, after all the pining over the loss of Leni in his life, he now knows "that she was somewhere definite" (408). However, he does not see the fault in his thoughts. His whole life with her was largely punctuated with his internal and stated ‘worries’ that she would be hurt in one of the protests which she attended. Even now she was worried that one of her fellow Communists must have gotten her into this situation. Yet, the thought does not even cross his mind that those whom he currently worked for — Weissmann, Mondaugen, perhaps even himself — were responsible for the internment at whatever camp she may be at.

He asks Mondaugen for assistance, knowing that his friend has been close to Weissmann for longer than he has. And it is revealed that this camp, of which many more exist, is deemed a ‘re-education camps’ and is one of what we call a concentration camp today. He comes to figure what these camps really are or at least comes to his own conclusions. While he still likely puts much blame on the organizations which she advocated for as opposed to the one he works for, he knew something needed to be done both to extract Leni from the camp and to prevent Ilse from returning to it. But he, unsurprisingly, was too cowardly, or perhaps too scared, to act yet. In his future, sitting beneath the Wheel of Zwölfkinder, he realizes this: that he refused to act in that moment where he could have enacted change — saved his family — and so now he lies here hopeless. The moment "when at last he wanted to act, there was nothing to act on" (409). Many moments like this occur to Pökler — and to many characters within the novel or people outside of it — where the time to act could save a person, a country, or a world, and yet that time is left until mere seconds too late, passing the window of change, falling to the ground outside of it without the hope of ever getting back up.

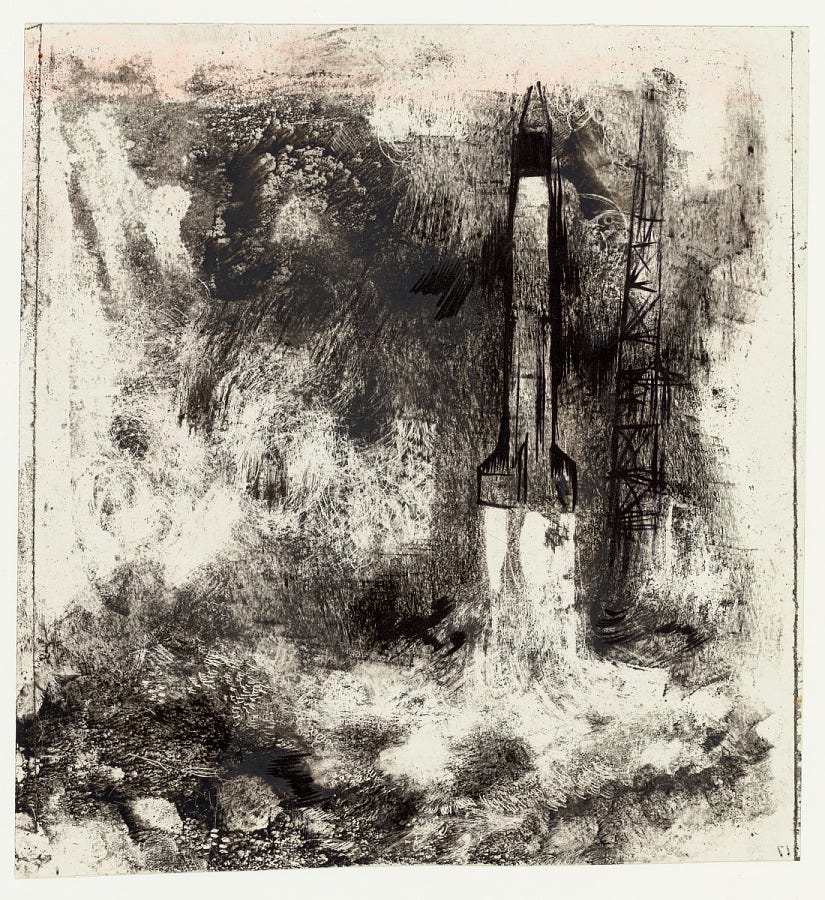

During Ilse’s initial visit, the rocket engineers and higher ups allowed her to watch a test launch, signaling to him (though again, his realization came far too late to do anything) that her freedom, too, was under Their control. She, and therefore Leni, were being kept somewhere where any word they spoke, anything they claimed to be happening, would fall on helpless ears who could not pass on the information to anyone else. The test which Ilse saw was, given these early stages of the rocket design, a failure. Pökler described the arc that the rocket was supposed to follow — a rainbow-like pathway traced by gravity — and she asked him where the rocket would land at the end of this supposed rainbow. Knowing it was meant to destroy, Pökler settled on telling her of the end goal of this development (or what he lied to himself about the end goal being). He said it would one day take people, possibly even her, to the moon. So, Ilse pictures herself held inside this rocket,2 not realizing that a fulfillment of this vision would not grant her a glimpse of the moon but would lead to her death and the death of all she touched.

Recall that the birth of Bianca stemmed from subjugation and rape via the scene in von Göll’s Alpdrücken, and that Ilse is a parallel given she was conceived after Pökler returned home from seeing that film to enact the same form of sexual subjugation upon Leni. As discussed (in 3.10), that, because of this type of birth, Bianca would have no possibility of true nostalgia, for she had no true home which she was born into to long for, similarly would Ilse lack the knowledge of a home. So, it is here that Ilse stares at the “map of the moon tacked to [the] fiberboard wall” (410) of an engineer’s cubicle near Pökler’s. She pined that this, perhaps, given the coming success of her father’s project, this home would be attainable. We know that the achievement, or even the seeking of the achievement, of this plan would lead not to a return home (nostos) but pure pain (algos) — the seekers of home only finding solace in the uninhabitable.

Pökler wonders how he could have led Ilse to this wish and considers telling her that the reality she seeks is pure fiction. But instead of righting a wrong, reclaiming what he had lost, or even saving her from the camps, he lies to himself again. He believes, or tricks himself into believing that he believes, these camps really are solely for re-education. So, as he falls asleep, Ilse nearby, and he begins to dream of “a map without any national borders […] in which flight was as natural as breathing” (410). It is within this dream that Pökler somehow either witnesses or is a literal part of a dream someone else had long ago3: one Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz, typically referred to or known simply by Kekulé. This scientist, living from the early- to late-19th century in Germany, was an organic chemist who discovered the structure of the benzene ring — the typical six carbon ring connected by alternating double and single bonds. It was this structure “that revolutionized chemistry and made the IG possible” (410) which he discovered by epiphany when dreaming, in 1865, of Ouroboros, the snake eating its tail — a symbol of self-destruction or suicide which would eventually be what stemmed from the benzene ring: it giving rise to the new possibilities of synthesis, be those plastics or weapons of mass destruction. The ring appeared to be useful of course, but the symbol — the metaphor — should have been heeded as the warning of what else would stem from it.

Jung himself posed the theory that all of humanity had the same pool of ‘dream material’ in which dreams were drawn from. Though, given we all dream differently, it seems that the dreams chosen correspond to the needs, desires, or answers to the problems of the dreamer. They are not God given gifts sent to advance the world but are symbolic representations of the things we desire to know. This traditional idea, that they stem from God, gives them an inherent goodness, “But how is it we are each visited as individuals, each by exactly and only what [one] needs” (410). It is because, due to the fact that these dreams represent what we want or ‘need’ to know, our dreams and interpretations of dreams can be analyzed however we wish them to in order to fulfill that answer or desire to our intended purpose. It is the same thing when members of the “IG go to séances” (411): for, as we saw during Walter Rathenau’s séance (1.19), despite these warnings from the ‘other side’ that Rathenau gave to the members of the IG and the Nazis, they only heard what they wished to hear, interpreted things that were said and predicted in ways that would benefit them, not for the warnings that they were intended to be. Similarly, though Kekulé saw the snake as the structure for the benzene ring (which it technically was) as an epiphany to create, he did not heed the symbolic warning behind what the structure could lead to in the end. And Franz, dreaming of his ‘natural’ flight on the moon, may also be misinterpreting or ignoring the implications of the dream’s symbolism, hence why he rethinks telling Ilse about the truth of her moon-dream and instead lies to himself about the ‘re-education’ camps as a place that could keep her safe.

The dreams that may lead to these discoveries are often pushed by agents “who are now allowing the cosmic Serpent […] to pass” (411). The pointsmen4 of the world — those who created “a switching-path of some kind” (410) to reroute history to Their liking — create situations which force the desires of their ‘underlings’ (like Kekulé) to dream dreams which will be interpreted to Their liking.5 One of these pointsmen was Liebig (another 19th-century German scientist) who converted Kekulé from being an architect to a chemist (switching the tracks from one life path to another). Liebig here parallels Clerk Maxwell’s ‘Demon’ — a hypothesized supernatural being who, without putting in actual work6 would be able to “concentrate energy into one favored room” (411). It is also thought that this ‘Demon’ was more a “parable about the actual existence of personnel like Liebig” (411) as opposed to any actual theorization of the possibility that such a creature or machine could exist — the parable being that certain ‘Demons,’ or people in higher strata, are concentrating power or effort toward their own chosen goals7. It is similar to what we saw as Slothrop entered the Mittelwerke (3.2) where the shape of the tunnels held numerous symbologies ranging from the SS (as in the Schutzstaffel) to the double integration used “in the guidance system of the A4” (411) and more. So, based on the pointsmen’s desires which controlled Kekulé, knowingly or unknowingly, he “went looking among the molecules of the time for the hidden shapes he knew were there” (412). While Kekulé could picture and diagram various molecular structures, it was only the benzene ring which stumped him — the shape of it was unseeable. Their will rendered his vision possible; and so, he saw the Ouroboros in his dream and discovered the structure of this six-carbon ring, thus creating “new methods of synthesis, so there would be a German dye industry to become the IG” (412).

Kekulé not only dreams of the Ouroboros, but dreams of Jörmungandr8 as well. He (or Pökler, who is examining the ideas of Kekulé’s dreams through his own dream that started with his flight to the moon) sees Jörmungandr’s statement that “‘The World is a closed thing’” (412). But mythology has no power here; the spirits and Gods possess words, stories, prophesies, yet have nothing with which to enact these visions, for “The Serpent […] is to be delivered into a system whose only aim is to violate the Cycle” (412). We have deteriorated from a world built on this symbology to one that depends — necessitates — ‘productivity’ and ‘earnings.’ Systems are supposed to take in energy as input and produce energy as output. However, The System — our hyper-capitalist structure — takes all it can and gives nothing in return. It violates every law in the name of profit; concentrates all the power without putting in the work. We will remove any humanity or belief for the blind obedience of the dollar. Yes, every “animal, vegetable, and mineral, is laid waste in the process” (412); the destruction of the world, to Them, lies deep below the importance of The Market, for The Market is Their God. Yet this System is only buying time; men knowing that their lives would end — that their children’s and even grandchildren’s lives would end — far before these animals and vegetables would cease to exist for good, needed Their own moments to extract the most pleasure from the World that They could. It is a mere series of steps, leading from one extraction to the next, that will benefit Them through the exploitation of all who They consider ‘lesser.’ And despite the knowledge that this System is designed purely to the purpose of this exploitation and extraction (this synthesis and control), many still wish to live within it, but this “is like riding across the country in a bus driven by a maniac bent on suicide” (412) — this bus driver being the same that would drive you straight into a Heidelberg, a bastion of the Nazi party during WWII.

In his (Kekulé’s and/or Pökler’s) dream, he imagines stepping off of this bus, allowed for a moment to observe that which surrounded it in the natural world, and was let back on by the Lord of Night, a propagator of war itself, checking to make sure you belong here — which, let me tell you, you do. It is your home. The nostos that you sought. We are now all children born out of this lust of subjugation, rape, and death — we are Ilse, Bianca, Gottfried: the children and grandchildren of those who were subjugated by those who destroyed our world. So Kekulé discovered the benzene ring just as Pökler (a student of Laszlo Jamf) helped discover the V-2. They each had a dream which they thought was borne from their own subconscious desire but was in fact borne from Theirs. The former crafted the means to achieve the latter: from organic chemistry to the synthesis — the concentration — of death. While both scientists believed they were the inventors of their life’s work, we will always wonder, “who, sent, the Dream?” (413).

And with a blending of Pökler’s dream (recalling his lessons from Jamf) with Kekulé’s, we see Laszlo Jamf ask, “Who sent this new serpent to our ruinous garden […] not to destroy, but to define to us the loss of” (413). This was the question: was the vision sent to end all that we knew, or was it the definition of our new era? These pieces of knowledge were gifts to be used for good, to be taken from the vein into the body to ease the pain, and yet in our dreams it was whispered to us that “‘They can be changed’” (413), so we changed them. We altered nature to our own desires. From a natural substance that we could see and interact with, to a schematic that could be written and chemically altered via equations on paper. Debris to plastic; plastic to death.

Pökler awoke from the dream and saw his work over the coming days ease up a bit. But just as soon as his life became easier, he returned to the cubicle to find Ilse gone — sent back to the camps. This threw Pökler into a rage, cursing and blaming Weissmann, chastising the idiocy of his peers for something they did not do. But he will wait to confront Weissmann until he knows he can do it with grace, in the meantime considering himself a Victim in a Vacuum — a slave with no master, a man with no lover, a father with no child, just someone trying “to reach through and connect” (415).

An insanity crept in on him. He saw the war gathering nearer and nearer, wrote himself paranoid notes, dreamt of conversations he had with Leni. And all this time, the Rocket grew closer to perfection. His insanity grew with the increasing success of the rocket, until one day, things settled, and he believed he could stand to finally speak to Weissmann. Their first conversation, on the surface, was entirely unrelated to the reason Pökler wanted to speak to him. It appeared merely as a discussion of numerous new findings and possibilities regarding the rocket’s development which could improve the cooling system. However, below the surface of the explicitly stated facts was the true meaning: “he had been negotiating for his child and for Leni” (417). Pökler understood that he was being tested by Weissmann and blackmailed by him at the same time. Weissmann was using the threat of Leni and Ilse’s internment to ensure Pökler would inhabit his work completely. It was understood by both that Pökler could not merely put on the face of the rocket engineer but would have to become it. Until Weissmann could see no difference between the man and the job, wife and child would remain unseen. It is a familiar power structure at work here — the Nazi, the demagogue, even just the employer, holding the livelihood of one’s family over a pit of flames until the worker dedicated themself in mind and spirit to the War, the Market, or the job.

When he achieved the first step in this dedication as Weissmann wanted, Ilse made her second visit. She returned, looking differently than she had before. Of course, with time passing at that age, bodily and facial changes occur quickly, and with the internment in a camp of the sort she was in, things would occur at wild rates — especially in regard to the changes her mental state has gone through. But nonetheless, he questions whether or not it is even her. That thought did occur last time as well, yet now it is far more prevalent. There is a true possibility that it is not her.

‘Ilse’ tells him that Leni and she were separated — Leni being moved to another camp. So, Pökler immediately knows that this is a test to break him. If Pökler were to overreact now, either explicitly questioning Ilse’s reality or raging at Leni’s transfer, Weissmann would know that he had not fully inhabited his role. He would know that Pökler still has his own full will and desire, that he is the man and not the job. So Pökler let these ideas fester in his own mind, questioning the reality that is being presented to him, recalling memories of Ilse — when they all still lived as a family — in order to compare to the girl with him now.

One day, out of the blue, Ilse still being there on her second visit, Pökler was given “a paycheck with a vacation bonus” which included “No travel restrictions, but a time limit of two weeks” (418). Another test — perhaps to see if he would return, ready to dedicate himself to the Market and the War once again. Ilse chose their destination: Zwölfkinder. Teeming with the lives of displaced children — only children, not adults — it is the same now abandoned park, holding the great Ferris Wheel that Pökler lays under in the present telling of the story as he remembers these events of his past, waiting once again for the umpteenth coming of Ilse, unsure if another return will ever occur.

Up Next: Part 3, Chapter 11.3 — pp. 419-433 (the end of the chapter)

Keep in mind that this is all occurring well before Weissmann went by Blicero — before Katje and Gottfried came into the picture. It was during the development of the V-2/A4, not during the use of.

Spoiler for end of book: This is clearly paralleling the placing of Gottfried within the V-2 rocket in the final chapter (4.12) showing that she, in some way, is analogous to him, just as the both of them are to the yet-to-be-met Bianca.

The fact of being within a certain place (the dream) while said event occurring at separate times calls to mind Bodine’s use of Oneirine at the end of 3.8, where his ship and the sub of the Argentinian Anarchists met in three-dimensional space but not in time.

Remember: A pointsman (also known as a switchman) is a railroad worker who specifically will switch the train tracks from one rail line to another (think of the ‘trolley problem’) and who also works the signals. Pointsman (the character) is also named so because of this implication.

I would like to point out that on page 411, line 8 begins with a parenthesis: “(after you get a little…”. However, it does not seem that this parenthesis is ever closed. Another one begins later, near the bottom of the page: “(later witnesses have suggested…”. That one is closed right at the bottom of the page: “just that symbolic shape . . .).” So, it could be a set of parentheses within another set of parentheses, but despite scanning and looking over coming pages, I do not see any closed parentheses. So, the possibilities here are either that it is a typo or that it is intentional. My assumption is that it is an intentional inducer of paranoia, referencing Ouroboros itself — something that both opens and closes, yet this section possesses something that does not close. Interpret this one as you will. Or… maybe it just is a typo, or a way to fuck with you. If I had to guess, it’s most likely the latter.

(*Note: After writing this, with help from others, I learned that the Bantam edition does close the parentheses after the ellipses of “it shouldn’t work but it does. . . .)” (411). Though I prefer to go with my original theory. Or why not both!

‘Work’ here being actual physical work — force multiplied by distance of the applied force (W=f*d). Rearranged, this equation would turn into distance equating to work divided by force (d=W/f). So, without work, movement (distance) would be impossible, meaning Maxwell’s hypothesized ‘Demon’ would be breaking the second law of thermodynamics.

Note: See Chapters 4 and 5 in Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 for more on Clerk Maxwell and his ‘Demon.’

And there could be a Marxist analysis here, saying that those in power who are concentrating things to their will do not necessarily need to put in the ‘work’ that your typical layman would have to to get what they desire.

The World Serpent within Norse mythology “which surrounds the World” (412).

Learned from looking up the Greifswalder Oie that von Braun was there in 1937 (and this is one of the few times P. gives us a year: "Pölker moved to Peenemünde in 1937". von Braun lurks behind the text, his leadership occupied in the fictional realm by Weissmann; who is at most only partially inspired by von Braun... The details about Peenemunde and Griefswalder came to Pynchon via Walter Dornberger's 1954 V-2, which was likely an important source for P. In fact, this is interesting, Dornberger worked as a consultant at Boeing as an Operation Paperclip transplant from the Nazis; P. could have known him. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Dornberger

This Rilke reference is not to one of the elegies, but to a quote as P. says, but he doesn't give the whole thing: "Everything once, only once, once and no more. Us too once. Never more often. But this having once been, even once only, this having been earthly seems irrevocable.”

I also dwelled on the open parenthesis. My edition -- the new penguin edition with the wrong page numbers--doesn't have the close parens you report in the Bantam.

Asta Nielsen barely had any upper lip atall. ...