Gravity's Rainbow - Part 2 - Chapter 2: Ivy League Intelligentsia

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 2 - Chapter 2: Slothrop's Nude Chase Scene

Shortly after Slothrop threw the crab out to sea, Grigori the octopus followed it, consumed it, and, likely as he was conditioned to do, returned to his handler, Dr. Porkyevitch, a man who only had any place in this whole conspiracy because of support from Pointsman. But Porkyevitch himself was once caught up in the Bukharin conspiracy: a Russian communist movement, the country whom the rest of the Allies, Pointsman and the British included, quickly turned against once the War had ended — or, in reality, had turned against far before. And now Pointsman, at least to the estimation of Porkyevitch (who himself may be a bit paranoid), is using him for his last effort, the plot against Slothrop, just as the capitalist Allies utilized the communist Allies for their own benefit: to end the war and create a furtherance of their own nefarious goals, throwing out the Reds once they were done with them.

Now that the Nazis are purportedly done for, the “Electricity is on tonight, the Casino back in France’s power grid” (190). The world, to the unobservant eye, is returning to normal. Casino Hermann Goering seems to be back under the control of the French. But, as Slothrop likely sees, fascism has never left. Sure, the menial facilities may be left to the original owners, builders, and citizens, but the name remains, forever now the true leader and conditioner of the masses.

Slothrop and Tantivy make their way down to dinner where Katje awaits, still Venus-like in her “emerald tiara” and “a long Medici gown of sea-green velvet” (190). Is it reality though, her being a goddess of love and lust, or are They once again playing with Slothrop’s intellect and insatiability, pitting him against the one thing he cannot resist? Well, as he moves to sit down to dinner, the seat next to her happens to be the one that is open, and she herself sits talking to a two-star general, making Slothrop just as jealous as he needs to be to continue not looking into things too much. And the flirtation comes at the right moment as well: a little footsy under the table. Slothrop cannot help himself anymore, so begins a distraction: a ballad to his friend’s ability to drink like a fish. And while the room is loud, boisterous, and merry, Katje is able, willing, to say to him what he’s been hoping for: “‘Meet me in my room’” (191).

Of course, he agrees, though his paranoia still runs at full force. He knows this is all too good to be true — that things are lining up perfectly when they should be anything but. So, he and Tantivy move into the bathroom stalls for a private conversation where Slothrop begins his first vocal questionings of the events. Tantivy initially acts confused, plays dumb for a bit as if he too is now realizing along with Slothrop that things are in fact a bit coincidental. But Slothrop does not relent, and Tantivy being the friend that he is (a true friend, as opposed to those pretending) reveals what little he knows: Teddy works for the higher-ups and is “‘receiving messages in code’” (192). Yes, Tantivy was hired on for the same plot, but he never would have guessed things would be this deranged. He has come to see that Bloat has become far more radicalized than he would have imagined, having been his friend for so long; yet, Bloat has now changed.

Their friendship, Tantivy and Bloat’s, stems back from “The old University connection,” (193) and Tantivy knows that Slothrop is well aware of what that means. It was (still is) the purpose of the Ivy League — “a peculiar structure that no one admitted to” (193). “‘Sure,’” replies Slothrop. “‘In that America, it’s the first thing they tell you. Harvard’s there for other reasons. The ‘educating’ part of it is just sort of a front’” (193). These institutions may put out lawyers, doctors, entrepreneurs, people who will go on to edit The Paris Review and know exactly which stories to publish — but what they’re really there for is for a whole separate sort of intelligence. It’s the reason those like Tantivy, Bloat, and Slothrop are often scouted for by their country’s intelligence agencies. Because they are above the average person, in a way. But they are also malleable, proud of their intellect and willing to use it for something else, often without asking too many questions, or at least knowing that they shouldn’t be asking those questions.1

At midnight, Slothrop enters Katje’s room, to once again find her in the exact outfit, pose, and lighting that he would find the most alluring. However, as the day has gone on, perfect moment after perfect moment, his tolerance seems to be waning. Yes, she once again poses against a backdrop to look like a classical painting; yes, her wardrobe is filled with the sexiest outfits that Slothrop could imagine; and yes, Katje does admit to Slothrop that she was only being kind to the general who he was jealous about earlier. He can see though that it has all happened before, and despite his insecurities — “Slothrop wonders if his fly’s open” (194) — he gets to questioning her as he did with Tantivy. Though the questioning is more of a prodding since he doesn’t want to be wrong and lose his chance.

And he sure does not lose that chance. Slothrop begins to undress her, slightly clumsily, muttering oboy to himself. She is Aphrodite “Born again . . .” (196), yet this time instead of rising from the foam of the sea, she does so out of her dress, and a darker side is revealed. Sure, that pale translucence that so heavily tempts Slothrop shines from her skin, but from the side he cannot see — or at least the side he refuses to look at — “there is still a dark side, her ventral side, her face, that he can no longer see, a terrible beastlike change coming over muzzle and lower jar, black pupils glowing to cover the entire eye space till whites are gone and there’s only the red animal reflection when the light comes to strike” (196).

When she has fully emerged, they fuck and she feigns her enjoyment of it, for it is not entirely willing on her part. Not that Slothrop knows that or admits it. She is, as she was to Blicero, still a slave to Them. She does not fuck Slothrop because she wants to, she does so because she must. It is part of the job, and no matter which member of the capital-T Them she escapes, another one always manages to scoop her back up, enslave her once again with lies, and tell her that they will be the one to treat her well, to give her the position she deserves. What else can she do but relent?

Sex leads to sleep, where Slothrop snores “like a rocket whose valves, under remote control, open and close at prearranged moments,” (197) keeping Katje from falling fully asleep throughout the night. Sleepless nights then lead to fighting, running around the hotel room throwing objects (which Slothrop believes/knows to be props placed there by Them) and eventually, when Katje blankets him with a tablecloth, she says, “‘Watch closely, while I make one American lieutenant disappear’” (198). And that is exactly what she is about to do, though she initially realizes that this comment may have been a bit too on the nose, perhaps coming out subconsciously, and proceeds to distract him once again, before they retreat back into sleep, with the one thing he cannot refuse.

When he awakes, rising out of the red womb, he finds that his status as a lieutenant actually has disappeared, or at least the thing which identifies him as such has — his clothing.2 This robbery strips him entirely bare. He is naked and thus is nothing. He is a blank slate to be transformed however They wish him to be transformed. So, blank and persona-less, he rushes through the conspicuously empty hotel in pursuit of the thief, the only aspect of him that is shining through now being his pure and predictable Americanness, which lands him in the center of a croquet match played by Teddy Bloat, some unnamed General, and a group of hilariously ostentatious women. As they take him back to his room to change into a uniform that Teddy Bloat is willing to donate to him, it turns out that all of his belongings have been ransacked as well, further solidifying Slothrop’s erasure from an American Lieutenant into a blank slate, and his subsequent rebirth as a British officer. Though, why would we now turn the prototypical American, so carefully built, into this? Because Pynchon will be observing the American Post-War state through the eyes of the British state during the war; he will be observing the new colonizers through the eyes of the old colonizers, the new capitalist imperialists through the old.

It also appears that Tantivy has spoken a bit too much — revealed to Slothrop something he was never supposed to know outright — and has also disappeared, no trace left behind. He goes out to search for Tantivy only to find a colonel who, though he sees Slothrop in a British uniform, later mistakes him for a Nazi. It seems even the higher-ups are aware that, whether in Britain, America, or elsewhere, the Nazis are beginning to work their way into the exposed seams of the world.

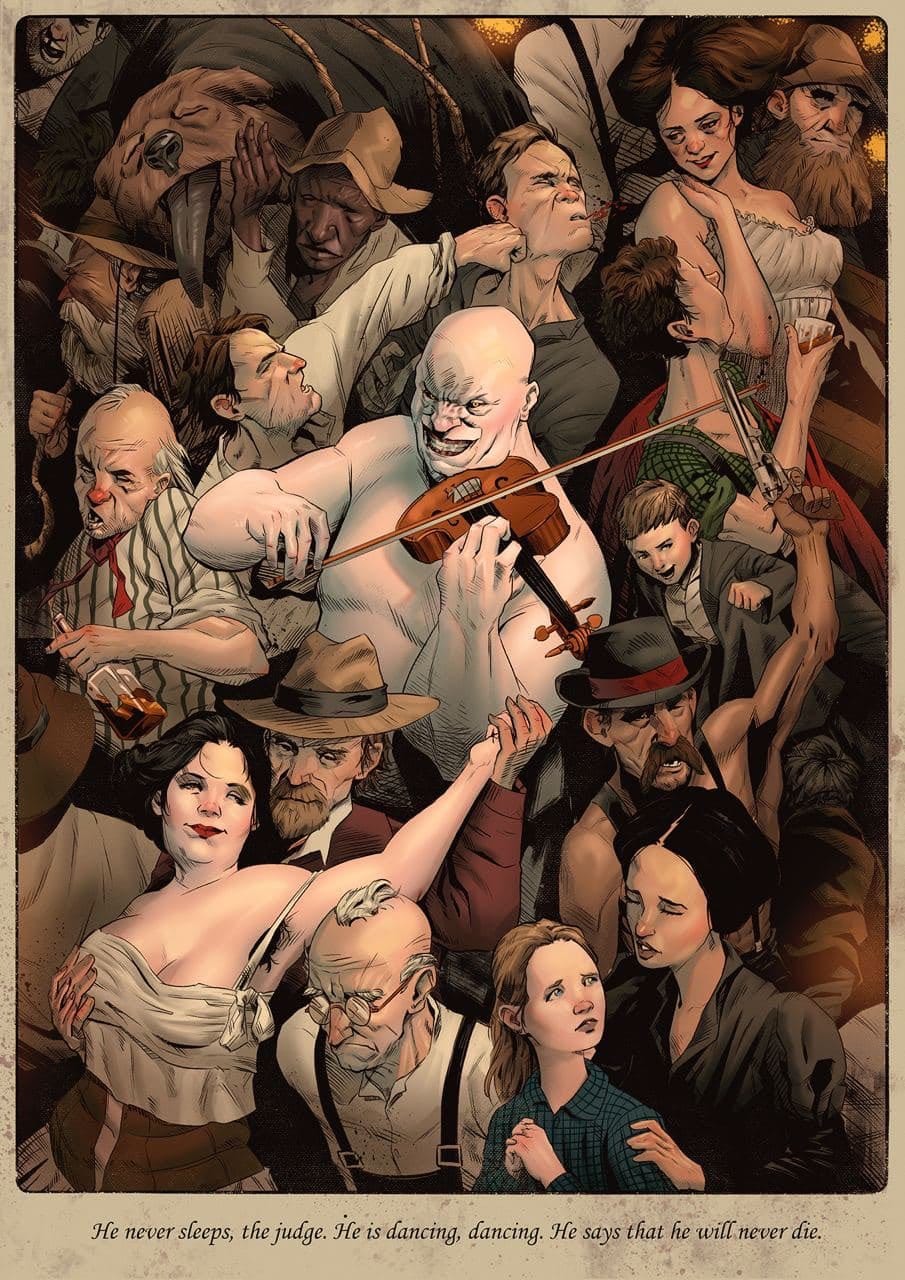

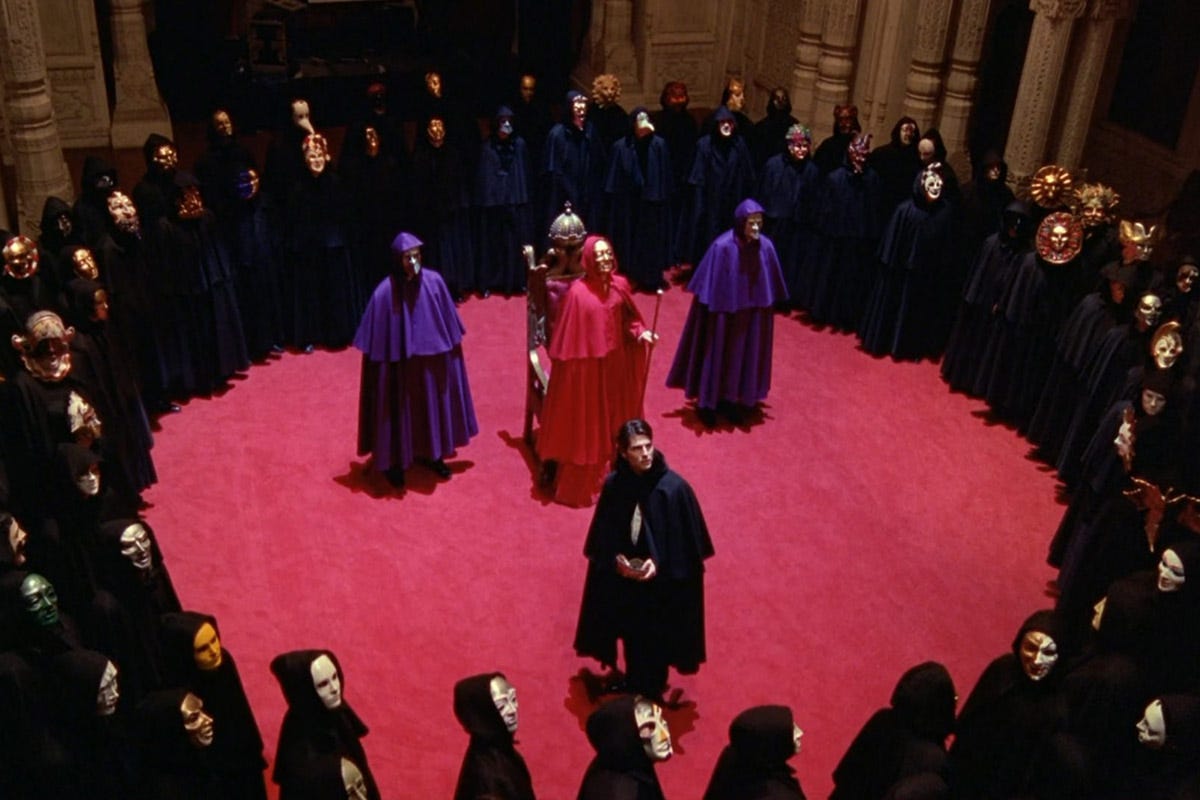

So Slothrop enters a room: a chilling scene which initially appears to be a private gambling room where the wealthy can bet absurd sums of money and win or lose to likely no true benefit or loss to themselves — because what is ten thousand to someone who can afford to bet ten thousand. But parallels begin to take shape in front of his eyes: this isn’t just a room; it is the world — the private quarters where only the Elite are allowed to rest and trade. Where they sit comfortably in their “Empire chairs” that are “systematically hidden from the likes of Slothrop.” Wherein “hang long chains, with hooks at the ends” (202) used for whatever sinister purposes.

It is a room where everything that is said to be used for something specific “is really being used for something different. Meaning things to Them it has never meant to us. Never. Two orders of being, looking identical” (202). The room, the world, is perhaps where stocks are traded — see Them telling us that we have just as much of a shot to make it big with the right investment. But is that what they’re really for? Or maybe the room is the real purpose of war. Not, as they tell us, “The mass nature of wartime death,” but the “Organic markets, carefully styled ‘black’ by the professionals” (105). He sees this now because as he becomes more and more desensitized to their attempted abduction and conditioning of him, he also becomes more aware of the true workings of the world around him. He was always aware, of course, but things invariably come to light more so when one is entangled within them.

It is not just him either who has come to these realizations that they are being used by the Elect — by Them. Members of his familial past3 were those same American, and before that, English, Preterite. They served the Elect. “The first American Slothrop had been a mess cook or something,” (204) ensuring that his superiors were oh so well cared for on their journey from England to America, only for them to repay him by puking up the meal he made for them all over his shoes. And now, our modern-day Tyrone Slothrop is English once again, wearing the uniform of his past Preterite genealogy and being spoken down to by his superiors: “‘Didn’t they teach you […] to salute?” (202).

What else can he do but relent? Run through it all again, in reverse? Across the beach as rain falls against his frantic face; back into the bar obscured in smoke to the point that he cannot make sense of a thing; into a room filled with people but not the one he needs to see. Nothing makes sense. He is looked on in pity by those who deserve pity themselves. Back, now, into that room of hidden symbols where he finally sees Them playing at Their games, gambling, perhaps, for his soul. Because — British or American or blank slate — he is the Preterite. He is what They need to maintain Their place up high. He is that grouping of lonely, oppressed individuals who work their lives away to live while They toss another ten thousand into the pot, not really caring or noticing if it is doubled or lost.

So, what can he do? Nothing, by himself at least — “He thinks he might begin to cry. How did this all turn against him so fast? His friends old and new, every last bit of paper and clothing connecting him to what he’s been, have just, fucking vanished” (205). They will take every last thing from us until we have nowhere to turn but to Them. And when we stagger back to Them, soaked and dripping wet from rain or tears or sweat, They will open up their arms to us, telling us how glad They are to have us back, and we will retreat willingly into Their embrace.

People often say that Part 2 is the breather, or the easiest Part of the book. And while that’s true on a surface level, I do feel like that notion conditions readers to not look as deep into what is being said. It did for me at least. But don’t let the simpler plot fool you. Part 2 is riddled with meaning. Read with as much care as you would for any other part of this wonderful novel.

Up Next: Part 2, Chapter 3.1

It will be covering the first ten or so pages of Chapter 3: pages 205-215 (or about halfway through 215) of Part 2, Chapter 3.

Pynchon himself (before becoming a writer) went to the Ivy Leagues and eventually began working for Boeing where he saw certain things that led him to quit and write books of this sort — condemnations on the world run by the Military Industrial Complex which uses institutions such as Ivy Leagues to further Their goals, gathering young, naive souls who don’t know enough about the world to turn them away. Or, who just need something to pay the rent.

This is the first instance of many throughout the novel where Slothrop’s clothing (i.e. his identity) is stolen, forcing him to take on an entirely new identity to continue on his journey.

Explored at length in Part 1: Chapter 4.

wait the Bukharin conspiracy was anti-Stalin; maybe Stalin was being a bit paranoid himself but he famously purged Bukharin and his supporters presumably sending Dr P into exile to Britan.

Stalin was probably right to purge Trotsky and probably wrong to purge Bukharin IMHO

To a paranoid, all differences of opinion are indication of conspiracy.