Gravity's Rainbow - Part 4 - Chapter 7: Seeking Heaven

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 4 - Chapter 7: Tchitcherine and the CIA, Memories of Wimpe, Marxist Dialectics, Oneirine Theophosphate, Tchitcherine's Haunting

Vaslav Tchitcherine, last seen looking out over the Argentinian Anarchists at the Lüneburg Heath (3.32), has been forced to abandon this post due to his being tailed by “Nikolai Ripov of the Commissariat for Intelligence Activities” (700) — yet another CIA analog, following the Committee on Idiopathic Archetypes (4.1) and the Committee on Incandescent Anomalies (4.3). This one seems to be a bit more straightforward, being a one for one representation of the CIA rather than the more obscured symbolic forms. The path of transformation takes us from the purely symbolic Committee on Idiopathic Archetypes, being an organization which suppresses non-standard (in the capitalist sense) forms of wealth accumulation, to the Committee on Incandescent Anomalies, one whose activities have more specific commodity based grounding and are now an analogy rather than pure symbol, to the Commissariat for Intelligence Activities, which could only ever represent the Central Intelligence Agency in everything but exact name. And this transformation is exactly how people’s knowledge will evolve in the coming years of the real world, evolving from something incomprehensible and seemingly docile to more and more tangible entities which eventually would be seen to be ‘closing in’ on us all.

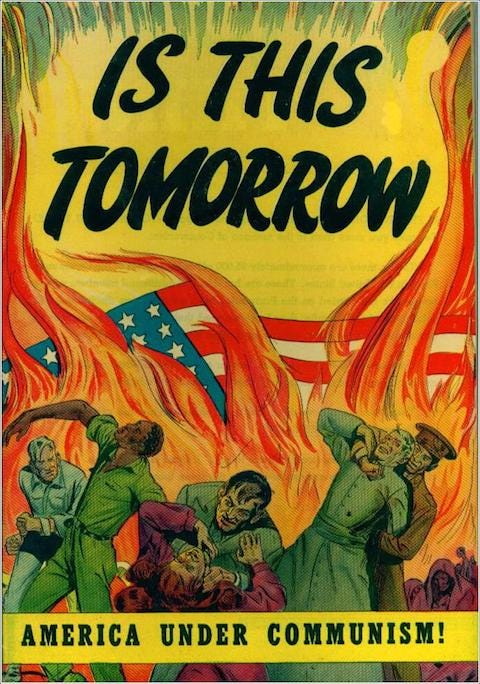

Tchitcherine is specifically being hunted by this CIA man because, if you recall, he is the Soviet/Russian analog to Slothrop, being simply another version of Slothrop, but representing a different Ally power (in the way that Marvy also represented a different side of America or that Enzian represented Africa and the other genocided or oppressed classes of people around the globe). With WWII’s end, as we have seen, the Russians may have contributed to the end of the War in more ways than most Western countries, and yet due to their Socialist/Communist form of governance, they will be hunted and culled by the purportedly ‘just’ method of leadership — the Capitalist nations. The CIA, as we have seen when they were named the Committee on Idiopathic Archetypes (4.1), viewed non-capitalist forms of survival as unacceptable, because if they were seen to be valid and effective forms of governance in one part of the world, this could cause Western citizens to possibly desire a similar change in their own system — the exact thing the Elite class is hell bent on preventing.

Džabajev, Tchitcherine’s companion all the way back when they had originally drugged Slothrop and stole some of his hashish (3.9) — also present at Tchitcherine’s meeting with Major Marvy and Chiclitz (3.27) —, has taken off as well, abandoning Tchitcherine in the process and posing as Frank Sinatra in town. Tchitcherine, alone, recalls Wimpe, the IG man who sold Laszlo Jamf’s then recently developed Oneirine as a literal ‘opiate of the people’ — a product which could be used to anesthetize the masses while keeping them addicted, thus forcing them to continue contributing to the capitalist system both to fuel the addiction and to further anesthetize them to their situation. But in this memory, Tchitcherine brings up another ‘opiate of the people’ — political narcotics. Politics, in the pseudo-democratic, capitalist sense, provide the same inherent anesthetic and indoctrinatory properties as opiates. First, they provide the numbing factor to the pain around you, both providing the actual pain that comes with addiction while also numbing the same pain through the ‘use’ of the system, believing that a candidate who wins could solve the pain for good. Secondly, it provides the forced contribution, since independent of the candidate, whether you win or not, you will inevitably be thrown back into that cycle. But there is an antidote to this ‘opiate’: Marxist dialectics.

Marxist dialectics provide the socio-economic framework in which to view the capitalist system and its associated politics. While the continued use of the ‘opiate’ (this form of politics) will only ever numb the pain of the problems surrounding you, these dialectics could thus be the only thing to remove the pain entirely. The system in which we are stuck in is impossible to escape from without the willingness to lose something important — ourselves or our loved ones through death. It has grown too powerful and all-encompassing that it will not go without a fight. And those who would usually be willing to take up that mantle are now unwilling to do so. While religion applied a purpose to death, our capitalist society sees death as the epitome of inconvenience. And this is not to say that religion’s given-purpose to death justifies many of the evils of organized religion, it has simply perfected the methods of getting followers to die for its cause. However, just as Pirate and Katje did (3.25), a new framework of death could replace the current. Currently, our fear stems from the idea that we will lose our individual capacity to consume and, in turn, lose our ability to experience individual pleasure. But these dialectics provide a new framework. If the ability to ‘consume pleasure’ and ‘experience history’ no longer sit at the top of our mind’s podium as the peak of life’s purpose, then death may not end up being so terrifying. In a world where this consumption and experience is only another ‘opiate’ to numb the pain of existence, what if there was a way — though it would risk our lives in the process — to remove Their grasp on us and, with that gone, much of the unnecessary suffering in the world. If what we consider important in life changes from the satisfaction of consumption to the accomplishment of “help[ing] History grow to its predestined shape […] knowing your act will bring a good end a bit closer,” (701) then death may not appear so terrifying. For, in death, you will know that you have accomplished what actually matters in life. Not consumption, but change.

During this conversation of modern politics as an opiate and Marxist dialects, Tchitcherine and Wimpe begin to shoot up Oneirine theophosphate. When the name is spoken, Tchitcherine initially questions Wimpe, asking if he means thiophosphate, ‘thio-’ being a chemical prefix indicating the presence of sulfur in a compound. Wimpe corrects him, stating, no, he meant ‘theo-,’ indicating the presence of God. This divine presence is shown through the unique hallucination that Oneirine produces. Firstly, recall that Onerine produced the effect of time modulation, allowing events to occur in time but not in space such as with the Argentinian Anarchist’s U-boat meeting Bodine’s ship (3.8). But here we also see that “hallucinations which are unique to this drug” (702) are another prominent feature, providing an equal distortion to all of the body’s senses despite being “‘the dullest hallucinations known to psychopharmacology’” (703).

So, if Oneirine encompasses the very presence of God, how could it also evoke the dullest aspects of life? Well, these hallucinations appear to be as similar to life as they could be, if only for “the presence of the dead, [or] journeys by the same route and means where one person will set out later but arrive earlier” (703). These hallucinations (known as ‘hauntings’ by its users and researchers) are similar to what many view heaven to be like — our own exact world, with all its pleasures and means for consumption, but in a sinless realm that has these ghostly apparitions of our past and in which time will not exist, for it will be eternal, thus leading to the indiscernibility of spatiotemporal events, similar to how the U-boat and the John E. Badass did (3.8). And finally, the drug also leads to “the discovery that everything is connected,” (703) just like Slothrop’s paranoia before meeting with Solange/Leni — the time when he realized the numerous plots he had experienced and become a part of were all interconnected in the most obscure of ways. Yet here, in this Oneirine induced Heaven, it is less conspiracy and more a natural interconnectedness. Or is it? For, this is not the reality of Heaven, it is the ‘opiate of the masses.’1 It is an anesthetic — a perceived interconnectedness which will make the hallucinator feel as if their world is heaven, as opposed to Slothrop’s understanding that the world is (currently) a series of horribly conceived plots by a group of Elites. It is a religious, deific distraction. And religion, in the Marxist sense, is a halo over the society that has created it. A means of distraction and anesthetic in the same way that Oneirine is; a thing that must be replaced with a proletariat mass philosophy if we ever hoped to relieve the fear of death.

Tchitcherine’s Oneirine haunting comes as such:

Tchitcherine’s Haunting

The main figment of Tchitcherine’s haunting is an interrogation by Nikolai Ripov, that same agent of the Commissariat for Intelligence Activities (CIA) mentioned at the start. The agency man is said to have the ability to illicit whatever information, faithful or fabricated, that he desires. It is his job to do as such — to determine or follow the desire of the agency and draw out said desire from an undesired individual. This would both render the outcome attainable while also getting rid of a figure which could, now or later, negate that desired outcome.

And speaking of dying in either the capitalist sense or the Marxist-dialectical sense, this CIA man assures Tchitcherine that nobody wants him to die. That his life is his to do whatever he so chooses with. That despite his incessant worrying (a very reasonable worrying, I should say, given the situation he has been forced into) he really is a ‘free’ to live.

Tchitcherine sees a figure appear, and though "He doesn’t recognize her […] it’s Galina, come back to the cities, out of the silences after all" (705). Galina was with Tchitcherine back in Central Asia during his exile, assisting in the distribution of the New Turkic Alphabet (3.5). It was said that she was from the city — "the city snows and heatwaves of Galina’s childhood were never so vast" — but that "She had to come out here to learn what an earthquake felt like" and wondered "What would it be like to go back now, back to a city" (3.5, pg. 341). Galina is the symbol in Tchitcherine’s haunting of this idea: that a collective mission (i.e. the distribution of the NTA) may very well serve a greater purpose. Now, it should be said that this ‘collective purpose,’ the NTA distribution, was not exactly what it appeared to be to those distributing it. For in reality, it was a means of control over the population it was being distributed to. But nonetheless, the idea of ‘bettering society’ was built into their work and so should have led to true happiness. However, in the end, she is back here, "No music heard, no summer journey taken" (705). There is a reason that this did not bring her true solace.

The final revelation in this haunting is about Enzian. Tchitcherine learns that he was made to believe his hunt for Enzian was a personal vendetta, an individual quest for revenge. But he was actually being used in the same way that Slothrop was, in that he was given specific information and paranoias which would lead him on a journey that would thus lead Them to find the major antagonist to Their plot: the Schwarzkommando — a group of oppressed individuals working to develop a means of fighting back.

So, Tchitcherine, still fearing death, going so far as to have "a deathbed conversion, out of fear" and having "to fight to believe in his mortality" (704), seems to be the antithesis to the idea that a removal of religion and an acceptance of collective action would lead to our willingness to die for a cause. Now, this is partially true, because as Joni Mitchell’s Cactus Tree says, a fight for true freedom does not necessarily remove our desire for something more individual and personal. However, could the failure to remove this fear be because we have been misled into fighting for a collective action that is not in our best interest? Well, it would not be surprising, since nearly every questline, individual or collective (i.e., individual: Slothrop’s journey, Tchitcherine’s hunt, or collective: the distribution of the NTA, the White Visitations Psi-section) has been guided by Their hand. Our only two collective actions seen through this novel that are thwarting Their goals are the Schwarzkommando’s operation and the formation of the Counterforce. Neither of these, yet, have led to disillusionment, and both are actively being targeted by CIA analogs. So maybe it is true, that this type of action and belief could thwart our fears while bettering our world, despite not always seeming like it. Tchitcherine, however, may never know this feeling. For, he is now sent back out into Central Asia for some other TsAGI operation, led by Their hand once again on a quest that could never fulfill that hopeful desire.

Up Next: Part 4, Chapter 8

Marx’s Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1844) is the origin for the idea presented here:

“Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their conditions is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusion. The criticism of religion is therefore in embryo the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.”