Gravity's Rainbow - Part 3 - Chapter 24.1: A Vision of Freedom

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 3 - Chapter 24.1: Pirate Prentice's Dream of Hell, Father Rapier, the Denizens of Hell, Radicalization

The Gospel of Thomas is an apocryphal account of the childhood of Jesus, covering numerous miracles from the restoration of a man’s life to the bringing of another man’s death. However, the claim that begins this chapter, “Dear Mom, I put a couple of people in Hell today,” (537) does not literally appear within the apocryphal work.1 The use of it calls to mind two disparate ideas which frame this chapter: the concepts of punishment and forgiveness, the former stemming from punishment being inflicted on someone attempting to thwart the Christian symbol of goodness, and the latter stemming from Jesus himself given he would grow up to bring about the concept of repentance through the realization and confession of one’s wrongdoing. This chapter largely focuses on these two ideas as well. Pirate, Katje, and many of the others who will join the Counterforce that we saw beginning to form in the previous chapter (3.23) have committed numerous mortal sins including (given they were all working for major intelligence agencies) contributing to the formation and spread of the Zone along with the reign of the Elite. However, it is always important to remember that these characters are not the Elite — not the ones with total power. So, with proper understanding, repentance, and a willingness to work toward changing the wrong one has assisted in causing, maybe these contributors could avoid their personal or, if you believe in it, spiritual Hell. They could be forgiven.

Thus, we are back (finally) with Pirate Prentice. We last heard about him at the very end of Part 2, where Pointsman, Katje, Mexico, and others sat on the beach as they realized that the White Visitation was crumbling partially because of them losing Slothrop (2.8). Pointsman, going crazy, was contemplating Pirate and his connection with Katje — how Pirate kept going down to the White Visitation “asking rather pointed questions about her” and “trying for a peep into this file or that” (2.8, pg. 274). But the last time we had actually seen Pirate in the flesh was when he first met Katje, dropped her off at the White Visitation, and began telling Osbie Feel about his fears and qualms with the system and project they were working toward (1.14). Of course, he literally began the novel as well with his apocalyptic vision of the end of our existence (1.1) — the exact thing that his participation in Their ‘plan’ would bring about. So, in reality, nearly every time we’ve seen him has had him questioning the system and what he was doing to further it. It thus comes to no surprise that he is one of the characters thinking about change.

Here he is again, a hopeful repentant to the system he had contributed to, wandering in his dream vision of an oddly innocuous version of Hell where people seem simply to be wandering through well monitored hallways, looking at book and art galleries, and consuming confections, all while he himself is following an absurdly long strand of taffy in order to get the official ‘tour’ of Hell. Pirate, walking in an area known here as Beaverboard Row, does see many of the denizens of hell ‘through’, as his companion here tells him, ‘a soldier’s eyes,’ envisioning the ‘offices’ of Hell being many of the organizations, projects, ideologies, and sins that he has contributed to: “A4 . . . IG . . . OIL FIRMS . . . LOBOTOMY . . . SELF-DEFENSE . . . HERESY . . .” (538). His companion, comparatively, sees things here as a garden — or that is what Pirate envisions a young and innocent woman would see in Hell (or is she seeing a personal Heaven?) given her noncontribution to its evils. He pictures a swing band even, singing about spirit, laughter, youth, innocence, freedom. And the feeling that this innocence and goodness gives off really is ‘con, —tay, — juss.’ It is a feeling that Pirate wishes he could reclaim for himself and for the world. As we know, this innocence has been eradicated by men that also found this idea as something to fight for, but actively destroyed for their own selfish reasons — Pökler contributing to the destruction of Zwölfkinder and the death of Ilse in the hopes that his scientific discovery would be something worthwhile (3.11) and Slothrop’s rape of Bianca in the hopes that his participation in the ritual and lusts of the Elite class would reward him with a true identity and purpose (3.15).

Near these ‘offices’ on Beaverboard Row, there is an unconnected building labeled ‘DEVIL’S ADVOCATE.’ Within it is one Father Rapier, a man analogous to a modern-day doomsday prophet, though perhaps with a bit more grace and intellect. His purpose, at first glance, is to invoke a sense of futility in the act of revolution. Pirate’s dream as a whole is a vision that is meant to help guide him toward the formation of a Counterforce and thus an actual revolution. But his type of action does not come lightly. We see death and horror in every revolution that has occurred throughout history, so of course within the subconscious dreamscape of a man bent on this act, we would also see some evolutionary psychology attempting to preserve its life, telling him to not act out of fear. But there is some sense in what he says:

There is the coming of the utilization of a ‘Critical Mass,’ what would soon be called the Cosmic Bomb. It has not been used yet, though its aura was trembling at the innards of the world, ready to tear apart those remaining seams that held anything together. Pirate would not have known about this bomb in any direct manner, because only the most ‘hep’ of individuals would have been ‘on the in’. However, his participation in this system and the anticlimactic nature to the end of the war in the European Front likely led him to expect something far grander to end the War in an official manner — something that would solidify and solder Their new reign over the world.

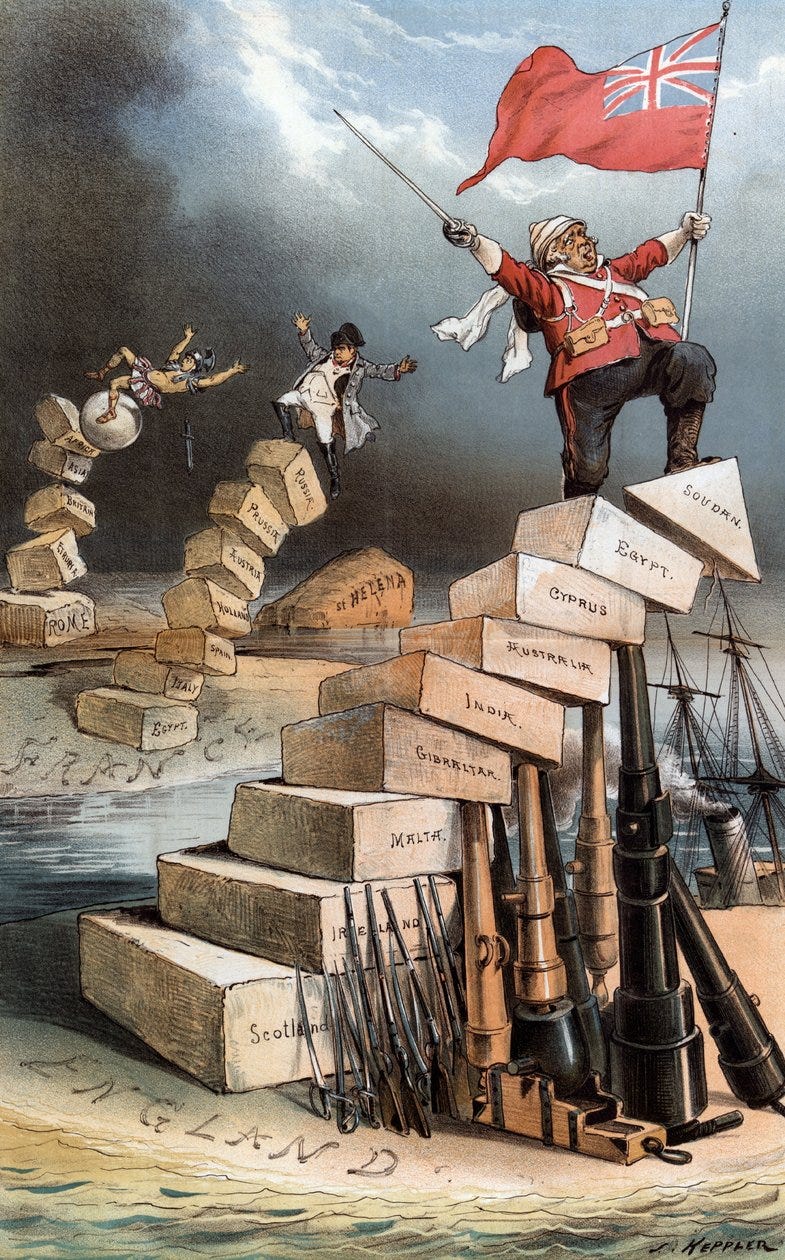

What, though, would have caused the Preterite to accept the fact of their downfall? Rapier argues that it is the possibility “that They will not die” (539). That the Preterite will die and be forgotten again and again as was the common form of existence for this group, but that the Elite would live on in whatever sense. Their wealth would be accumulated, Their names would be imprinted on plaques on the sides of buildings in universities, downtowns, and corporate centers, They would appear in the descriptions of charities, discoveries, and breakthroughs, They would be written about in books and encyclopedias, be taught about in courses at Ivy Leagues, be spoken about decades later, referenced in political contexts and otherwise. It would not matter, according to this train of thought, if we revolted, took them out, ended Their reign. For, maybe one or two of ‘us’ would be recalled just as a revolutionary like Marat is still remembered, but those kings and queens — those with the same last names, the III, the IV, the V, the VI, and so on into their dynastical reign — would be known no matter what. So, what is the point? It could, with great reservations, make things better for the acute present, but would anything really change?

Or, perhaps They are just as doomed as we are: what really is the remembrance of a name? If that is the case, then why worry? We will all live, die, and be forgotten. But this could just be “the most carefully propagated, of all Their lies” (539) — one to make us believe in the futility of revolt.

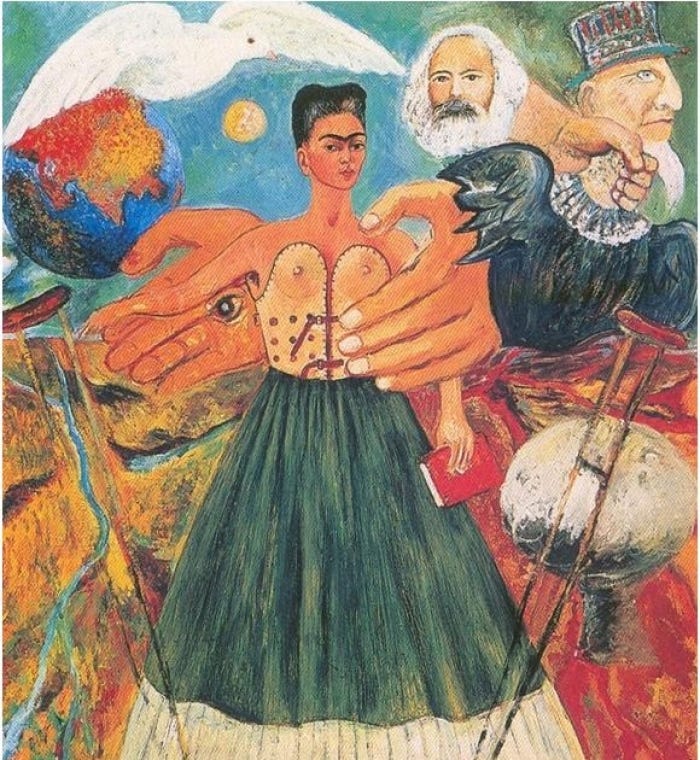

In order to find purpose in this ideology, “‘We have to carry on under the possibility that we die only because They want us to: because They need our terror for Their survival” (539). And this is where Father Rapier takes a turn. Maybe he is not a doomsday prophet, but someone to call to mind our doubts in order to teach us why these doubts were there in the first place — why we had any true qualms or fears within those deepest recesses of our psyche. He teaches us that Death, to Them, is a tool. We have been given the idea that like Them, we must be remembered, causing us to scrabble about, work to join Their ranks just like Slothrop sought to join in the vilest of manners, or even like Pökler attempted. It would lead us to assist Them instead of fight against Them, and this reluctance to fight would propagate Their existence without bringing us even an inch closer to our own elevation. They have given us the idea that we must fear death because we will leave the world both unremembered and unable to experience what will come. This is Their call for us to work solely for our own individualistic and monetarily beneficial purposes as opposed to the development of class consciousness and collectivism that would lead the Preterite and the Elite to becoming forgotten words. Yet this is Their definition. And we know They still fear Death as well, so could it all be a lie? Or does Their definition also apply to them? And anyway, like us, “They can still die from violence […] For every kind of vampire, there is a kind of cross” (540).

Rapier finishes with a disclaimer for the entire speech he had been giving, stating that its purpose was to bring to light the idea that They could die just like the Preterite. Coming to the realization that immortality through notoriety, status, wealth, a name, a child, or any other thing that could be carried on into the posthumous future, is not immortality at all. It is a lie meant to alleviate the fear that one would not be able to see the coming events of History. To take away Their sense of immortality would reawaken immortality in the Preterite, but not in the same sense of the Elite’s status of supposed Godhood, or in Their desire to continue on into infinity. Instead, this would be a Return, where the Preterite as a collective whole would render themselves immortal. There is no immortality on the individual level, but on a societal scale; if we were to reawaken our sense of oneness, our collective progression forward through history, we could overcome these ‘certain obstacles’ and ensure a collective immortality.

Pirate and the girl he listened to the speech with see a few denizens of his dream Hell: Sammy Hilbert-Spaess and Gerhardt von Göll. Recall that Hilbert-Spaess was the man whom Carroll Eventyr conducted a seance on at the White Visitation — parallel to the time period where Stephen Dodson-Truck and Katje Borgesius left Slothrop at the Casino Hermann Goering (2.3). His name was a reference to the quantum mechanical phenomenon known as a Hilbert Space which, within the context of 2.3, was analogous to Pynchon’s technique of mapping instances of history over similar other instances — for example, the various character parallels such as Slothrop/Bianca and Pökler/Ilse, the rise of the Third Reich in Leni Pökler’s timeline and the rise of the Fourth Reich in Slothrop’s, or even if we look in Pynchon’s other works, the search for the V-2 in Gravity’s Rainbow paralleling the search for V. in V., the search for Tristero in The Crying of Lot 49, for the Golden Fang in Inherent Vice, for Deep Archer in Bleeding Edge, and so on. All of these events have occurred and are occurring again at increasingly complex and impossible to parse degrees. Along with him, Gerhardt von Göll (der Springer), the infamous film director of Alpdrücken and possibly the Martin Fierro film with the Argentinian Anarchists, is the representative of the ‘artist’ become God/creator. He hypothesized that his films brought fiction into reality. For instance, as we saw in 3.8 when von Göll was meeting the Argentinian Anarchists for the first time, we learned that his film Alpdrücken brought numerous phenomena to life in the real world — the dream of Pointsman in which a dog named Reichssieger von Thanatz Alpdrucken was considered the nightmare itself, and then Thanatz stemming from this name to see itself reborn in Miklos Thanatz upon the Anubis. Whether this was all coincidence or happenstance, it does call to mind the power of the artist/director when they are given the opportunity to use their creations for more nefarious purposes. And even more importantly, it parallels Hilbert-Spaess’s analogy of recurrence and ‘mappings.’ So, these two coming to Pirate’s view shortly after his listening to Father Rapier’s speech just compounds the nature of what Rapier had said. Not only are They controlling the world in order to maintain Their false sense of immortality, but our fighting against Them (our Revolution, per se) is not us going against the unknown. It is not as terrifying as it seems — no jumping into the unseeable deep. It has all happened before and is happening again. It is as explicit as what we see on the movie screen, what we have seen in history books, or what we are seeing occur right now before our very eyes.

Shortly after seeing these two, he sees a man who he hasn’t seen before, St.-Just Grossout, a man who was tasked with infiltrating the Schwarzkommando. Pirate had not heard about this plot, likely not knowing much about Operation Blackwing anyway given he worked within an entirely different department of the White Visitation and so asks Grossout for the sitrep (situation report) on the plot. It is here that we learn another thing about how They work and how They lead our ‘fight’ astray. Grossout tells Pirate that he could inform him about the situation, but that by the time he finished, the ‘official’ narrative would have changed. It is similar to the various modern-day conspiracies that many Preterite are bent on ‘solving.’ In reality, so many of these plots that are being discovered don’t really matter at some point. There are enough that we know about2 to the point that seeking out the nuances and truth behind every single possible new revelation can be a distraction from the goal at hand. Yes, the real narratives are important — incredibly important at that. But they will reveal themselves as they always have, and a search beyond what is necessary, a sole focus on discovering the reality behind conspiracy, will distract from the more important goal of achieving the deconstruction of the Elite power structure.

Finally, Pirate sees Sir Stephen Dodson-Truck. We last saw him on the beach at the Casino Hermann Goering with Slothrop (2.3), sobbing and confessing to Slothrop that he was only ever sent to the Casino in order to continue the White Visitation’s study (and thus Their study) on Slothrop’s conditioning, i.e. the connection between his erections, or his sexual encounters, and the fall of Rockets. His confession led to his leaving, possibly of his own volition or because They had learned that he revealed a secret he should not have. Either way, the realization that he was being tasked with lying to and manipulating an innocent (at the time) individual led to his apparent radicalization. Pirate asks him here what led to this ‘change,’ this radicalization. He states that the steps toward his change began with getting over the shame — coming to terms with the realization that all he had done has been to serve an evil master and to make the world a worse place for the masses; often, people questioning their own moral and political ideology only ever refuse to change because it would cause this shame — hence why the first step is to let the shame wash over you and then to get over it. The second step is getting over the idea that one’s free will does not exist. While there is the possibility that They are controlling every one of us through propaganda, or, as Dodson-Truck jokingly hypothesizes, through “Radio-Control[s]-Implanted-In-The-Head-At-Birth,” (542) or even the possibility that our ‘free will’ does not exist solely on the basis of physics, does it really matter? If so, maybe none of what we do has any bearing on choice, but that does not alleviate us from the responsibility of attempting to make things in this world better. The question of free will can never be a cop-out for action.

Pirate, here, realizes the truth. He too was manipulated. From his trek out to the fallen bomb (1.4) which he saw from his rooftop (1.1) to his meeting and recruitment of Katje (1.14), to all his other actions within the White Visitation — it was all a lie. It was never for the betterment of his land, his country, his people. It was not even for the freedom of himself. Instead, he did have his free will stripped away for that time period. Pirate, and all the people currently within his dream of Hell, had been working for the betterment of the Elite. And it is here that they realize this does not have to be the only way forward.

Up Next: Part 3, Chapter 24.2

Weisenburger, Stephen. A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion: Sources and Contexts for Pynchon’s Novel. 2nd ed., University of Georgia Press, 2006, pg. 233.

For example, the JFK assassination which is largely explored in Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 or in DeLillo’s Libra, or in something that had yet to come by the time of the writing of Gravity’s Rainbow such as Iran-Contra. We can also see some of the futility in seeking out every answer within a conspiracy in Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge.

Your 2nd footnote reminds me of Proverbs for Paranoids 3. If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don't have to worry about the answers.