Gravity's Rainbow - Part 3 - Chapter 10: The Pain of Returning Home

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 3 - Chapter 10: Slothrop Awakes, He Meets Erdmann, Bianca's Conception, Singularities

Slothrop has awakened from his Sodium Amytal stupor — the second one since we’ve met him. Back in England, he was put under by his initial pursuers, those at The White Visitation, and he experienced his hallucination in the Roseland Ballroom and the trip down the toilet to fetch his harmonica. Here, in Potsdam, shortly after retrieving the hashish, he was put under by Tchitcherine who wanted to know what Slothrop was seeking given he believed it was the same thing he was here for. But unlike that first time, where after he awoke and recovered, he made his way out onto the streets of London to find another girl to sleep with, this time he barely has the energy to rise; all of these instances of pursuit and interrogation are beginning to really wear on him. So, he decides to doze off and have his own dream as opposed to the hallucinatory ones that have been recurrently forced on him.

His dream takes him to his childhood, a nostalgia — after the Jamf experiments but before he went off to Harvard. He is with his father, Broderick, watching a flock of birds being pushed around by wind and snow. He worries for them, seeing them struggling to maintain flight, afraid of how they may handle the cold. It is a gut reaction, a human one. His father’s form of comfort is to state facts, those about heart rates and warm coats of feathers. This is not a negative thing for, ignoring the harm that Broderick did bring upon young Tyrone in his past, he was really just attempting to soothe Slothrop. But it does show that, from the beginning, Slothrop’s humane instincts were thrown aside for more logical forms of thinking. Though some of those vestiges still remain as we see him attribute his sudden weight gain to a visualization of a humorous cartoon vignette as opposed to the more logical multiplication and enlargement of adipose cells (as his father likely would have explained).

Eventually, he decides to rise out of his drug induced fatigue and walks out the door only to find himself on an old, abandoned movie set. The set is filled with various remains, strewn all about, and the “girders 50 feet overhead” (393) recall one of the earliest lines in the novel: “Above him lift girders old as an iron queen” (1.1, pg. 3). Could this set be the parallel to the postapocalyptic world dreamt by Pirate in the opening scene?

The movie set, as a symbol, is the world. The actors are put in place, sometimes unaware that they are actors, and are set out to fulfill their roles; they are us, the people we interact with daily, and those we see on TV. The sets and props are placed to give us an illusion of the world we are in and are thrown out to rot when they are no longer needed; they are the banks, the towers we cannot see into, the factories in more tucked away parts of town, even the winding streets leading from our home to the store, the “places whose names he has never heard” (1.1, pg. 3). The props, the world, the cities, the streets, will all be thrown out. There will be “no lights inside the cars. No light anywhere” (1.1, pg. 3). And this is where Their plan, the plot of the film, is enacted. It is already written to Their specifications, and the plot — life itself — “proceeds, but it’s all theatre” (1.1, pg. 3).

So, it is no surprise that this is where he meets his Lisaura, Margherita (Greta) Erdmann. While Erdmann is the actual person whom he meets, Lisaura is the character from the Wagner opera he recollected earlier (3.6) who is her ‘fictional’ parallel. Lisaura was Tannhäuser’s (Slothrop’s parallel) lover who he wronged by spending the nights with Venus/Frau Holda.

Erdmann is travelling east in search of her daughter Bianca1 and has stopped in the film studios of Neubabelsberg for a bit of nostalgia and sentiment given she had worked as an actress for a few decades before the war. Here in Germany, she was filmed by director Gerhardt von Göll (also known as der Springer), the same director who would help the Argentinian Anarchists film their Martin Fierro film (3.8), who crafted his own nightmarish film Alpdrücken (learned about in 3.8), and who Slothrop was told to find in order to procure information from on the Schwarzgerät (3.1 & 3.7). Her roles with von Göll typically revolved around her being pursued by evil creatures or being bound, removing the possibility of escaping these creatures’ pursuit. In these pursuits or attacks, they (or as Slothrop believes, They), considered her to be “the Anti-Dietrich: not destroyer of men but doll [of men]” (394). Erdmann, and soon others, will be categorized as a doll — a wide-eyed figure, unable to react yet unable to look away. And Slothrop believes she has been conditioned by Them to act this way in the face of terror.

One of the films Erdmann happened to be a part of was von Göll’s Alpdrücken, the nightmare film which will tie together many characters and which possibly stemmed from the dream of Pointsman. She brings Slothrop to the torture set of the film and begins telling him about von Göll whom Slothrop does not yet know is the der Springer he is looking for. Von Göll went directly against Nazi orders and made a film about King Ludwig II: a mad king who died by drowning. His death was ruled a suicide after his body was found; however, like FDR’s death which Slothrop had recently learned about (3.7), and like JFK’s left to come, many questions still arose regarding the accuracy of this verdict. Could he just have been another leader taken out by his enemies? But, either way, due to Hitler’s desires, the film about him, Das Wütend Reich (translation: The Mad Empire), was never released. Instead, Good Society was directed and released, a film in which a major memorable scene was that of Erdmann being subjugated and whipped. The Nazi party, and many clandestine organizations with fascist tendencies in the modern world, apparently seem very keen on suppressing art that reveals the insane nature of leaders and the possibility of political assassinations, while wholly advocating for and enjoying those that depict forms of subjugation.

But this was von Göll’s unreleased film and his second film, respectively. The main film Erdmann remembers was his first, Alpdrücken — The Nightmare. It is on this film set that she believes she was impregnated with Bianca, the daughter she is searching for, by her regular co-star, Max Schlepzig — thus revealing that she was impregnated in a preconceived scene of torture and rape. This name obviously perturbs Slothrop, as he was recently given the fake-ID/AGO card to get into Potsdam/Neubabelsberg under the name the same name (3.7). When he shows Erdmann the AGO card, she realizes that They had gotten to Schlepzig, for the card is not a fake. It bears his exact signature. She knows that They want Slothrop here with her — Schlepzig by name, a symbolic parallel. And, with Erdmann’s paranoia coming to the forefront, Slothrop realizes that they are also parallels to each other: “What happens when paranoid meets paranoid?” (395).

Erdmann wants to explore the parallel between Slothrop and Schlepzig, asking him, Slothrop, to do to her what Schlepzig once did. She wants him to be cruel, to whip and harm her “‘Just for the warmth’” (396). She desires this for a sense of nostalgia, but not in the sense of fond memories of one’s past. Instead, she wants the original meaning: “The pain of a return home,” (396) the etymology stemming from the Greek nostos, meaning ‘a return home’, and algos, meaning ‘pain.’ We have seen this nostalgia through an early dream of Pointsman’s where he walked through the desolate, haunted streets of his childhood home (1.17, pp. 136-138), or as Pirate Prentice stood atop his home, staring over the dying landscape of WWII London (1.1, pg. 6). It is the complex desire to experience that pain of returning to one’s past. To return to it, fully bound by every sting. To know that, at one point, things were better — more bearable.

Even though Slothrop is not Schlepzig, and though he is not currently being directed by von Göll to torture and subjugate, it comes naturally, for “somebody has already educated him” (396). Given he is a representation of both America and the archetypal American, he was born with that natural ability in mind. It is not something that will come out of everyone, but something that lies dormant, ready to emerge when They call for it. For, it is no longer just Their ‘meadows and sky,’ it is ‘his.’ So, the subjugation begins, coming naturally, and Slothrop focuses on the “singular point at the top of [her] stocking” (396). Most will attribute that focus to a number of things — Pavlovian conditioning, the abundance of sexual advertising, pornography, and more. But for the American, for Slothrop, it all has to do with singularities.

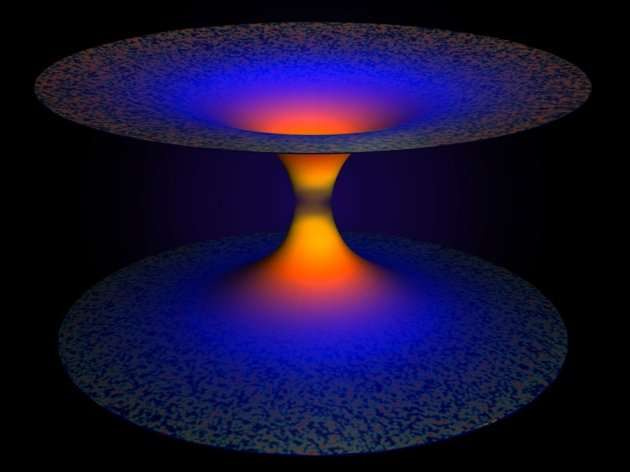

The singularity is a point of no return, something that has gone so far Beyond the Zero that it will remain beyond with no chance of nostalgia, for it cannot ‘return home.’ There are the definitional, explicit, and inferential forms of singularities at play here. Definitionally, the singularity references various scientific points: one being the point of no return for the black hole, where once you are caught in it, you — or even light — cannot escape. Explicitly, within the text of the novel, symbolic singularities arise: cathedral spires calling as points of no return to the easily governable masses, railroad switch points where tracks move from one to the other,2 mountain peaks such as that of Berchtesgaden,3 or the tip of the V-2/A4 rocket, where once it strikes the Earth, any whom it touches have no chance to return. So, knowing that Slothrop’s moments of sexual intercourse once led to the calling of the Rocket, and knowing now his current desire, Slothrop’s sexual desire is the calling point for this singularity.

There will be deeper zeroes to explore, points of no return even more impossible to return from, in a few mere months in Japan.

Similarly, Slothrop views this point of Greta’s stocking. Could she be a point of no return for Slothrop? Was she, as such, the same for Schlepzig, or he for her? And thus, Slothrop maps her onto Katje. As Slothrop is to Schlepzig for Erdmann, so is Erdmann to Katje for Slothrop. Born out of this nightmarish and time-bending orgy of subjugation and pain is, as Erdmann cries during her and Slothrop’s fornication, Bianca. Literally born to Erdmann, supposed daughter too of the real Schlepzig, conceived in the filming of Alpdrücken, and now a symbolic daughter of Slothrop (the archetypal American) and Katje (the escaped slave of true evil, Blicero); Bianca is the coming generation. She was born out of rape and subjugation, the representative of the modern child. She has no possibility of true nostalgia, for she has no home, and no Earth, in this world to return to, no nostos. All she has to seek is pain — algos — and she will seek this pain in the unfeasible hope that she can find a home.

This is officially the 50th post on the Substack! And I believe, if I’m tracking correctly, we’re right around 80,000 words. As usual, thanks for following along!

The next three weeks will be dedicated to the longest chapter of the novel, the famous Franz Pökler story. Usually, chapters take a week to write about, sometimes two for the longer ones. It is one of the most incredible, heartbreaking, and powerful stories ever told — one that could exist as a solitary masterpiece of a short story — so I hope to do it justice (it is genuinely one of three chapters that I have been most excited and most nervous to write about — the second and third of these come in Part 4). So…

Up Next: Part 3, Chapter 11.1 — pp. 397-407 (ending with the first two brief lines of dialogue on 407).

Another name to remember for later.

Pointsman’s name stems from ‘pointsman’ — the job title of the person who switches the tracks of the train (perhaps the tracks of history) from one path to another. Once that train is switched over, there really is no return.

Hitler’s respite in Bavaria. A beautiful scenic viewpoint of the countryside where the ur-fascists could view their demesne like a God. This, a kingly sight for a demon, shows another point of no return — that being the treasure one learned they could achieve by going to such lengths.

Bianca is also an italian name that can be translated into “white”, so perhaps Pynchon is creating here a contrast whit slothrope’s “schwartz” obsession.