Mason & Dixon - Part 2 - Chapter 44: The Survey Party

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 2 - Chapter 44: Ley-Lines Again, the Westward Line, Rose Quartz, Jonas Everybeet, the Sales Pitch, Darby and Cope, Matthew Marine, Moses Barnes, Mr. and Mrs. Price

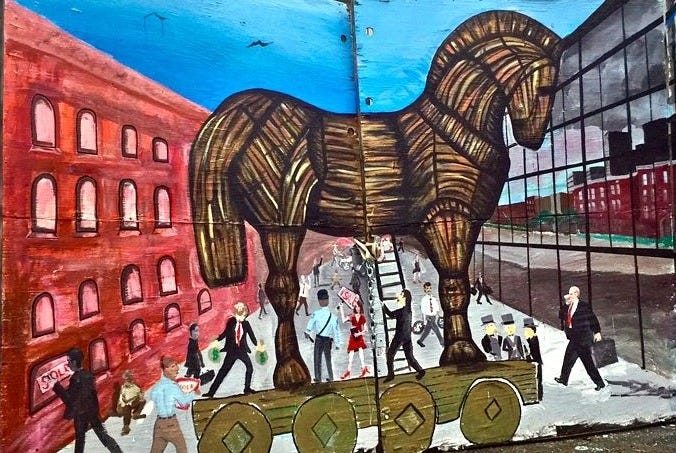

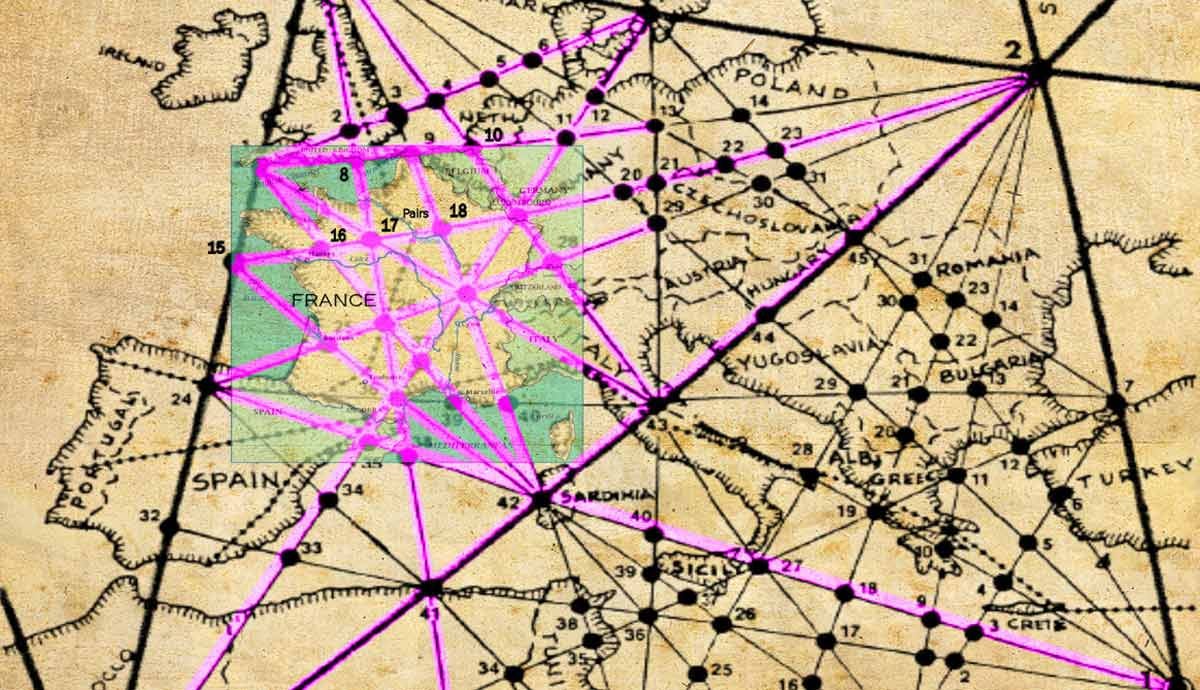

Cherrycoke’s Spiritual Day-Book once again tells us of the magical Ley-Lines that William Emerson once taught Dixon and his fellow students about back before Dixon ever became a Surveyor (1.22). When Emerson taught Dixon about them, he taught them as being perfectly straight lines that, through some unknown magic, connected historical structures built long ago — possibly due to the builders being more in tune with the spiritual world. Likely, this was an oversimplification which the white man of the future attempted to oversimplify through some more readily comprehensible explanation. Similarly, to Emerson, the Ley-Lines served as a metaphor for paths leading from point A to point B in the same manner that a singular chain would do, ignoring the various entanglements of something like our metaphorical historical chains. Another way to view ley lines would be as borders — again, paths leading from point A to point B that grew out of the same type of mind that decided linear history would be a beneficial concept to teach the masses. Here, however, they are described as airborne “invisible straight Lines, crossing the earthly landscape” where one could “in theory travel to the furthest reaches of the Kingdom, without once touching the Earth” (440). This most obviously sounds like the description of an airplane, which it partially is. However, on top of this it is a reference to the final chapter of Gravity’s Rainbow where it states that “the City has grown so tall that elevators are long-haul affairs” (Gravity’s Rainbow, 4.12, pg. 735). This chapter opened as a dream of the end of the world, describing this new technology of massive elevators used for this vertical travel. In my own analysis of that chapter (no spoilers) it states that:

Technology has advanced, new discoveries have been made, though very few of them have done anything to make our lives more bearable. We simply have attained a new means of doing the same thing we always have done: what Mindy Bloth of Carbon City calls ‘the Vertical Solution.’ This solution, using our new long-haul elevators to rise above the Earth, is not really something new since we’ve had planes for some time now, but Bloth states that it is completely different, giving some absurd explanation that airplanes only produced “‘a common aerodynamic effect […] involving our own boundary layer and the shape of the orifice as we pass it’” ([Gravity’s Rainbow, 4.12, pg.] 735-736). First of all, Bloth’s explanation of how airplanes and long-haul elevators differ in regard to vertical travel is some obscure and largely meaningless way to distract the riders from the fact that, in reality, this progress that they are seeing is nothing more beneficial than what they had used before. All it is, is a new way to create useless jobs, useless technologies, and useless distractions. For, this technology is not merely a way to produce profit by selling and building things we don’t need, but just as Bloth is doing, [is meant] to distract us from the reality of ‘the Vertical Solution’ (that being Rockets, not planes).

Progress, here, is a lie. Just as the ‘long-haul elevator’ was a useless new technology which did the same thing as a plane or a helicopter,1 just as today Artificial Intelligence does the same thing as a search engine or encyclopedia paired with a decent brain, so too do pointless societal progressions do to technologies that could actually bear something meaningful — artificial mathematical/legal borders compared to natural rivers or landscapes, for instance. And the epitome of this type of progress… well — “the most prodigious such Line yet attempted [was] in America, where undertakings of its scale are possible,— astronomically precise […] perhaps even higher and faster than is customary along Ley-lines we know” (440). This is where we find the surveyors, ready to “pursue a rise through the air, […] link’d to the stars, to that inhuman Precision, and are deferr’d to because of it, tho’ also fear’d and resented” (440). It is April of 1765. They are ready, finally, to embark west.

The journey begins back again at Harland’s farm where they have taken John Harland “on as an Instrument-Bearer” (441).2 Mrs. Harland tells the two that John had been “hummin’ ‘Love in a Cottage’” (441). Love in a Cottage was a play of which Mason had thought of back when he was seeking the secret Elite chambers and came instead across the effigies (2.29). The play followed two people seeking to escape an arranged marriage so that they could be together. But it turned out that the arranged marriage happened to be between them, symbolizing the attempt to escape the fate set out for you in society and falling into exactly what society wanted from you in the first place. Harland, therefore, is doing just this — thinking he is escaping the place that he has been allotted in this New World when in reality, the path he is instead going to take is exactly what those who built this society wished of him. It is similar to any person ‘escaping’ their boring life only to work for the same system that gave them that life in the first place.

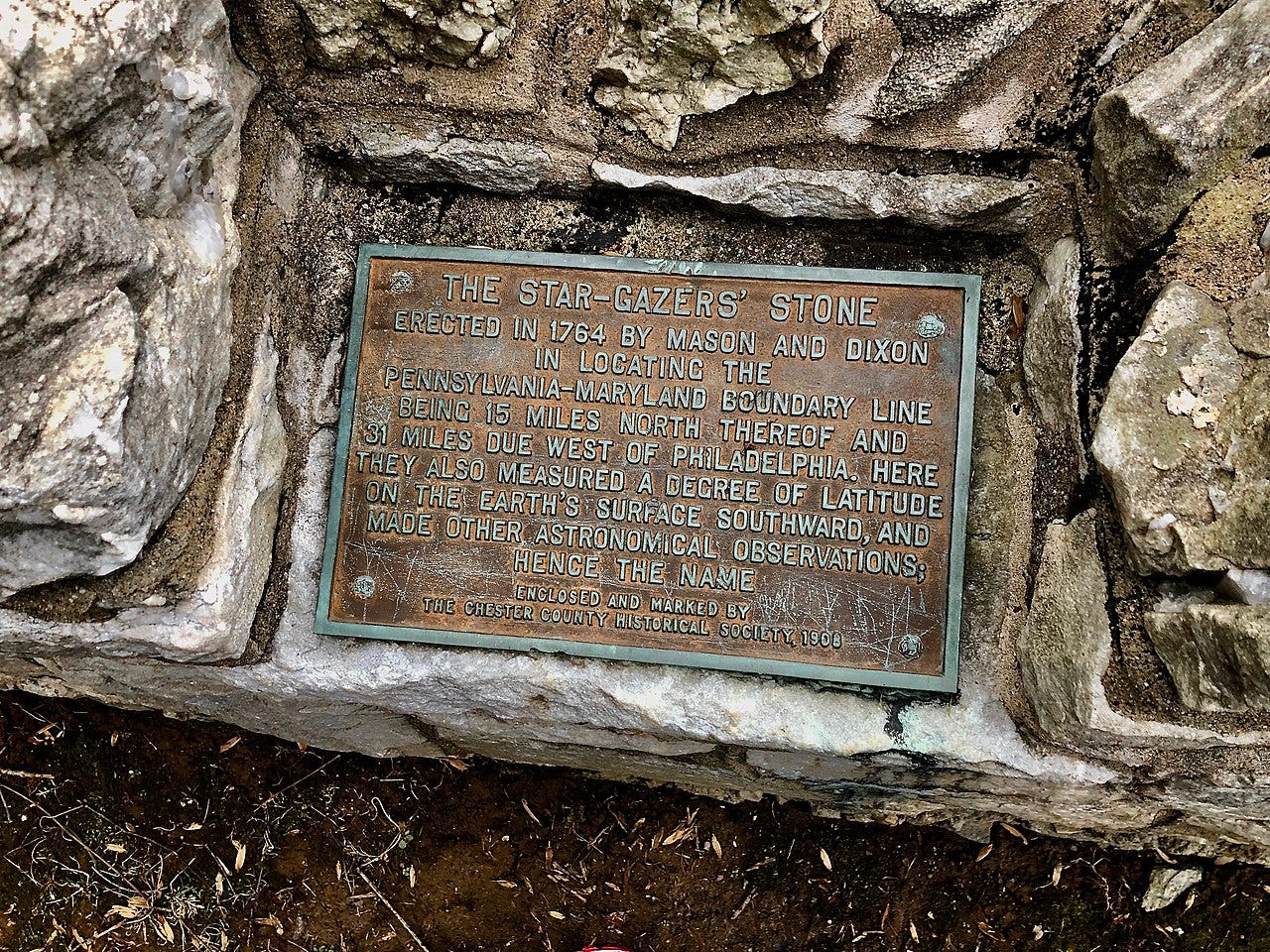

Robert Boggs, a man who “is presumably a hostler or wagon-driver for the party,” (Biebel, 181)3 ran by to tell them that someone near the Rose Quartz which marked “the single Point to which all work upon the West Line (and its eastward Protraction to the Delaware Shore) will finally refer” (441) was acting a bit strange. It is here that they find Jonas Everybeet, another man who will soon join their party as they head west: “in the time he travels with the Party, he will locate, here and there across the Land, Islands in Earth’s Magnetic Field,— Anomalies with no explanation for being where they are,— other than conscious intervention by whoever or whatever was here before the Indians” (442). Jonas was a scryer — a man who had the ability to look within certain objects and divine some insight in regard to that object or whatever answer he may be looking for. Here at this rose quartz, Jonas takes out his own scrying crystal in order to see what this line may bring, even giving Mason the chance to look within it. Mason’s reaction, seeing a pair of dark eyes looking back at him, is one of horror. Whatever he sees here — be they the eyes of God or Satan or something else — is angered at the future that this line will bring. But as we are well aware by now, no epiphany be it spiritual, physical, supernatural, preternatural, religious, or otherwise, will be enough to cause Mason, or Dixon for that matter, to question their part to play enough to stop their work.

Jonas comments briefly upon the magnetic anomalies that he so often finds, stating that their purpose evades him. He does, however, find that the Oölite Shafts4 — the Crown Stones — add another form of ‘magic’ to this world. He predicts that just like Benjamin Franklin’s Armonica, the line of stones will draw out a musical note that never existed here before, though it is unclear what that note will be. Of course, it is not likely that the note will be something pure and good. It likely would be a competing force, drowning out the music that may originally have existed here for centuries if not millennia. But this theory does not matter to Mason and Dixon. They simply believe that each member joining their Party is attempting to persuade them one way or the other to benefit themself. There couldn’t be anything else going on, right?

Harland and Everybeet are the first new members to the party. Now, here comes a man named O’Rooty, attempting to sell another man to them to bring along. O’Rooty rambles on like a door-to-door salesman telling Mason and Dixon of the top-notch axmen that he has on hand, rattling off a sales pitch and stating these axmen’s level of performance (“equal of any ten Axmen”), the quality of the ‘parts’ that come with them (“Finest double-bit Axes”), the warranty and return policy associated with them (“lifetime Warranty on the Heads, seventy-two-hour replacement Policy”), the possible personalization of the product being sold (“customiz’d Handle for each Axman”), and the artisanal and exotic methods used to produce something you couldn’t get anywhere else (“Swedish Steel here, secret Processes guarded for years”) (443). The destruction of the forests and natural landscapes is being sold to them like a set of cheap knives at Costco. These so-called artisanal products will be built of parts sent from all over the globe, destroying forests for lumber and using slave labor to mine ores, just to be sold to you in order to make the job you do slightly more efficient and convenient, only to end up, one day, in a landfill or floating among a pile of trash in the ocean. And it is not only this; labor, here, is also being sold. These men who have perfected their craft are now themselves becoming a commodity to be traded in order to survive.

The man that they eventually take is Stig — an axman we will see later.

Now we have John Harland as instrument bearer, Jonas Everybeet as scryer, and Stig as axman. Who next but “a ‘Developer,’ or Projector of Land-Schemes[?]”; “‘Kill him,’ advises Dixon, […] ‘And do it sooner rather than later, as it only gets more difficult with time’” (443). This developer is the analog to a modern-day real estate developer, building new neighborhoods and suburbs, contributing to urban sprawl and gentrification. And though Dixon being a land-surveyor in England had been a part of this form of land accumulation and segmentation, thus also contributing to the elevation and formation of the real-estate market, he is aware of the evils which accompany it. The longer one allows this type of person to weasel themselves into each city and each neighborhood, the harder it is to get them to leave. Homes will rise in price. They will all appear to be the same blank, gray slate — will require the demolition of historic sites and genuine craftsman homes. Mason, taking Dixon aside, believes it is Dixon’s hatred of this specific man. But no, Dixon is genuine. While he may be complicit in certain aspects of this project, this is something he will have no part of. It is a hilarious place to draw the line.

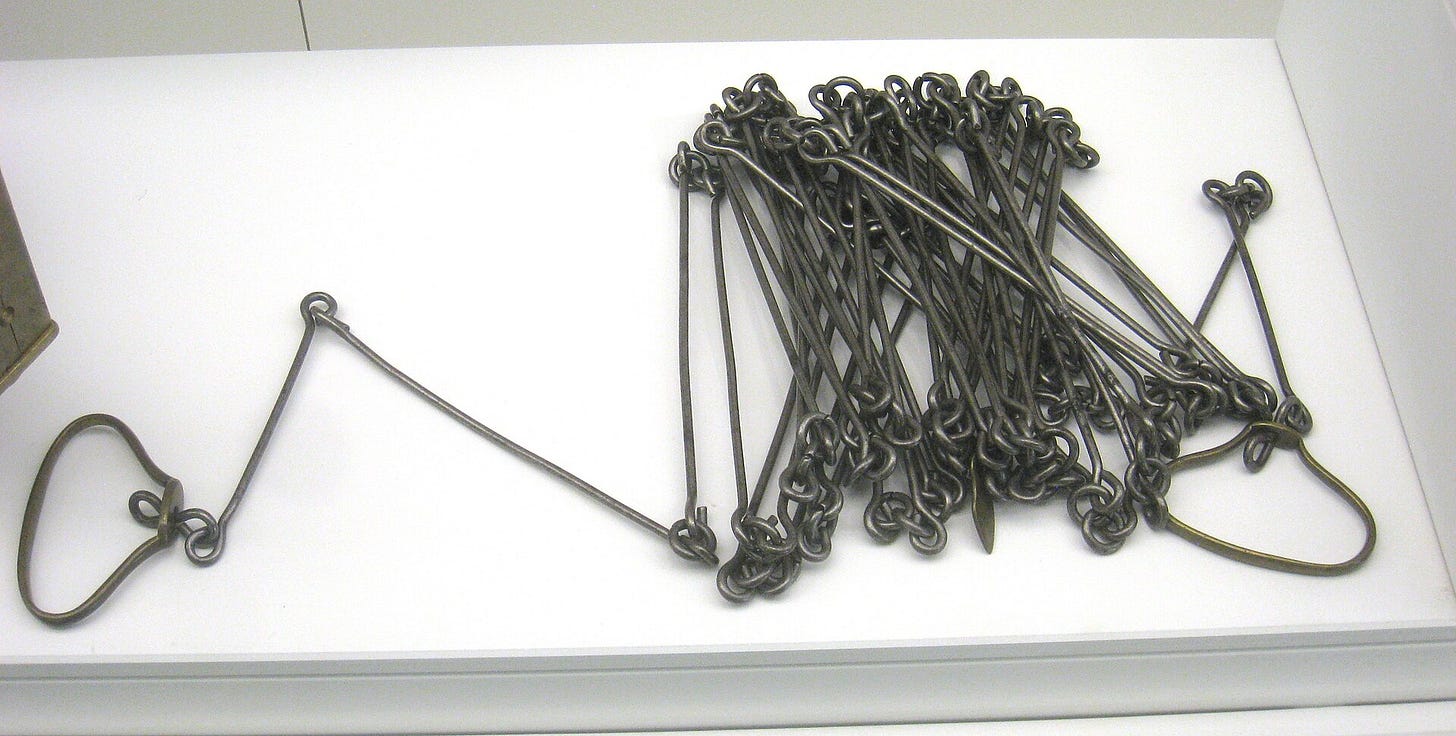

Two more men who are a part of the survey party are introduced, “Messrs. Darby and Cope” (444). William Darby and Jonathan Cope were the actual chainbearers who accompanied Mason and Dixon on their journey west. These two would set one man to stand in a certain location holding one end of the chain5 (this would be Cope) while the other would walk ahead so to measure precise distances along the line (this would be Darby).6

April 5, 1765, is “The first day of the West Line” (444). They have been here, in America, for a year and a half now and only today do they begin the work that would define them. April 5 is a Friday, the same day of the week when they sailed from Spithead, “Where the Seahorse left port of Friday, January 9, 1761” (Biebel, 182). And while Friday here is described as inauspicious, the knowledge of what happened when the Seahorse left on that same day of the week (1.4) reveals the irony in this statement.

This line begins by noting that on top of Stig — the axman that was sold to them recently by O’Rooty — the surveyors also have gathered eleven other axmen to assist them in tearing down the natural forests which ‘impede’ the way of Darby and Cope’s chain, again showing how American progress always entails some perverse destruction of the world in which those who lived before actually respected and honored.

Matthew Marine (another historically accurate instrument-bearer) comments on how the instruments used to map this westward line are being treated better than their bearers. And he is right, as no matter what happens, the paid-out wages of the laborers will always remain the same; no loss will be incurred. For example, if Harland were to fall out for some reason, then the five shillings a day which he was paid would simply go to another — thirty-five shillings this week, thirty-five shillings next week, the loss of a worker, and thirty-five shillings to the new worker the third week. There would be no adjustment in the cost other than perhaps a brief search for a new man which, in all honesty, would likely not cost much. However, an instrument is a thing which has already been paid for. The cost is one and done. The loss or destruction of such an instrument would mean the loss of those payments entirely, and an equal or possibly greater amount would need to be shelled out for another — a hundred shillings this week that could be the one singular payment, but if one lost the instrument, another hundred shillings (at least) would have to be shelled out. Thus, the machine is treated with more care than the man.

And again, another member of the survey party is introduced: “Overseer of the Axmen Moses Barnes” (445) — yet another historically accurate character. He is the slave driver — the manager. A man paid quite well but who is still a laborer under the true ‘boss.’ Yet, this pay and responsibility renders him confident and egotistical enough to strike fear in the axmen (the general laborers) who work under him. He sees himself as a soon-to-be Elite, just as many general managers tend to do. But the fact remains that he, too, is more replaceable than a simple instrument.7

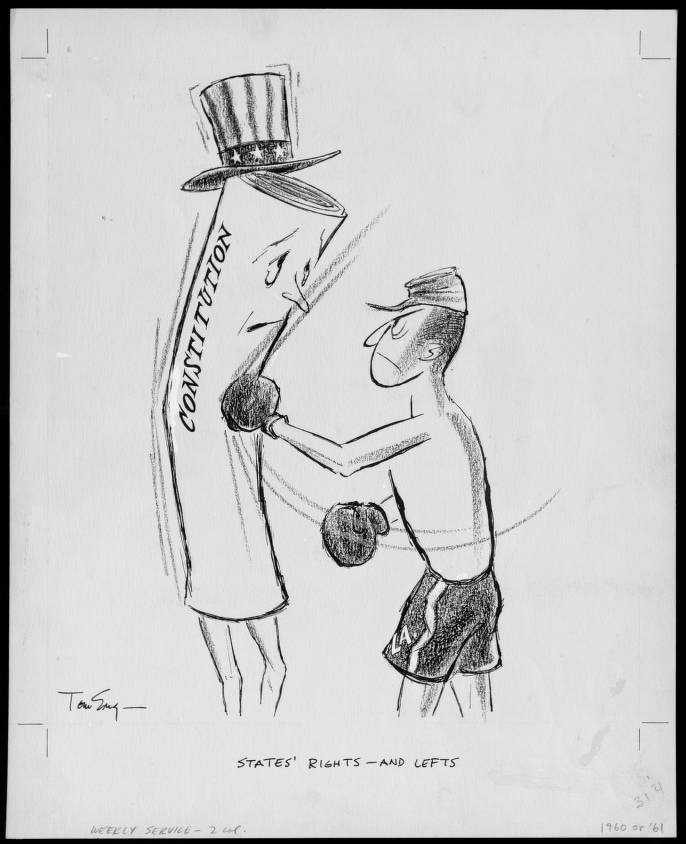

On April 10, 1765, just five days after beginning the journey west, the survey party “run[s] the Line thro’ somebody’s House” (446).8 Long ago, George Washington stated that “the West Line must contribute North and South Boundaries to Pieces innumerable,” (2.28, pg. 276) referencing how the coming line would separate various bodies — not just cities or states, but even homes. So here we see this prediction come to fruition at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Price., where the line not only splits their home in half, but their bed as well. The scene is comic, Mrs. Price feeling absolute relief that when she is on the Maryland side of her home, she now has no obligations toward Rhys Price given they were married in Pennsylvania. However, this also brings a massive number of societal absurdities to light. First, that which hopefully does not require more explanation, the absurdity and nonexistent nature of borders. Secondly, the absurdity of state rights in America, all being within the same country but somehow having completely different obligations, norms, and laws. Third, the absurdity of marriage itself, being — at the time and sometimes still today — a contract which cannot be broken despite growing frustration and hate. Fourth, the messy entanglement between marriage, religion, and government, none of which can separate one from the other but all of which want to exist in their own separate realm. And fifth, the lengths one must go to in order to break such a bond that is no longer desired.

The magnetic and spiritual pulse that Jonas Everybeet found within the American Frontier would never have sunk into such absurd swamps. It is not that these more traditional customs don’t have their own oddities to begin with. But if it is not apparent now, the formation of this massive group of surveyors — from men holding chains to men chopping down trees to men carrying random instruments to men surveying the stars to men managing various groups and on and on and on — and the abstract laws and decisions made on various other levels, has led to a country built on such incomprehensible entanglements that it forces husband and wife to literally roll their home down a hill to escape further entanglement in all of these realms.

In a perfect world, all of this could have just been solved with a conversation, maybe a fight, or a handshake, or a letter.

But, alas, this is America.

Up Next: Part 2, Chapter 45

Sorry if this essay feels a bit disjointed. The many character introductions, pieces of history, and plot progressions all jump around and make for a tougher piece to write about while trying to make it fluid.

The helicopter itself gets plenty of commentary in Gravity’s Rainbow 4.6 (which I write about in the second out of three parts on that chapter).

Remember that John Harland became heavily fascinated with their methodology and the possibility that he could gain some form of power/never-ending-commodity-based-pleasure if he were to travel west (2.23). So, it is not unexpected that he made this decision.

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.

And for the annotation from page 181 in reference to Robert Boggs, since Biebel got the quote from the M&D Wiki:

Mason & Dixon Wiki. August 9, 2015. http://masondixon.pynchonwiki.com/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page

Oölite is a type of sedimentary rock with specific grain patterns. One common type of oölite is limestone. Mason and Dixon used limestone markers on their journey west. Every one mile, a stone was placed, and every five miles, a ‘Crown Stone’ was placed which was this limestone marker, bearing Royal insignias, an M on the Maryland side, and a P on the Pennsylvania side.

A 66-foot-long surveyor chain knows as a Gunter’s Chain used to measure distances.

Note that two men each performing a similar task to achieve a certain goal have parallels to Mason and Dixon. We will see this comparison emerge as time goes on.

Nathanael McClean is also mentioned here. He was very briefly mentioned much earlier in Mason and Dixon’s arrival in America — late 1763. When Mason and Dixon were in the apothecary, discussing opium on their initial introduction to Benjamin Franklin, we heard of McClean. He was to be the steward of the entire survey party. Thus, all that pertains to Moses Barnes in terms of managerial ego also pertains ten-fold to McClean.

And again, Farlow — Robert Farlow — who is introduced here, is another historically accurate character. He “carried instruments and set out line markers” (Biebel, 182).

I'm honestly a far bigger fan of M&D than GR, and there's really no (free, at least) analysis that's nearly as illuminating or comprehensive as what you're doing here. Fair play, there's definitely a lot that goes into something like this.