Mason & Dixon - Part 2 - Chapter 41: Das Kapital

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 2 - Chapter 41: Elementary Particles, the Invisible Hand, Iron-Plantations, Lepton's Estate, Forms of Labor, the Calvert Agent, Lady Lepton, Great Chains, Elite Taboos

J. Wade LeSpark interrupts Cherrycoke’s telling of the story to tell some of his own.1 Cherrycoke just finished telling of Dixon’s journey south to Virginia (2.39) and Mason’s journey north to New York City (2.40). LeSpark begins by referencing a time when he had met Mason and Dixon, a fact which we somehow have not heard about until now. J. Wade met them at one Lord Lepton’s estate, Lepton being one of the figures who Dolly warned Dixon of while in a coffee shop, saying, “They imagine, that you and your Instrument will make of them Nabobs, like Lord Lepton, to whose ill-reputed Plantation you must be drawn, upon your way West […] Beware” (2.30, pg. 301). Lepton was an incredibly wealthy Lord who gave ‘a standing Invitation’ to J. Wade LeSpark to stop by whenever he so chose, thus giving this Lord close ties with the 18th-century version of an arms manufacturer/arms dealer, and giving this arms dealer a tie with... well, we will see what Lepton represents.

Lepton’s name references a subcategory of elementary particles. Under the category of elementary particles are fermions and bosons, and under the subcategory of fermions lie the two subcategories, quarks and leptons. The category of leptons contains electrons, muons, and tau-particles, plus the neutrino versions of each of these three leptons2 (as well as the antilepton version of each of these six, i.e. antielectrons which are also called positrons, antimuons, antitaus, electron antineutrino, muon antineutrino, and tau antineutrino). Importantly, leptons are specifically known to respond to minor electromagnetic forces, but not strong ones, hence why the negative electric charge of an electron is drawn toward the positive electric charge of a proton but not drawn to or repelled by any stronger electrical or magnetic charges (if they were, then all matter as we know it would certainly not exist). This characteristic of a lepton’s attraction and repulsion will not come to importance just yet — but keep it in mind.

J. Wade LeSpark (who I will refer to, like Pynchon did, as JWL, for most of this chapter) tells the story from his perspective. One day, he was traveling through the woods to arrive at the house of Lord Lepton. Whereas JWL was the weapons tycoon, at the house of Lepton he was “under the protection of a superior Power,— not, in this case, God, but rather Business” (411). Lepton, therefore, was not just one sect of the capitalist project like JWL, but was that Lord of the capitalist project itself. He was the man who worked the so-called ‘Invisible Hand’ of Adam Smith — a hand that was supposed to work via its own natural and innate properties. As Adam Smith would have said, his metaphorical Invisible Hand was proof that the Market would naturally acclimate to mankind’s self-interest. If things appeared to be spiraling out of control or heading toward a massive downturn, the Invisible Hand would work it out in time. Capitalism, being a natural economic outgrowth of mankind’s tendency toward free market trade (according to those like Lepton, JWL, and Smith), is a system perfected. And here we see the tethers that work the Hand stem from Lepton’s estate, rendering it to be a puppet controlled by a puppeteer rather than the God-like creature the capitalists wish us to believe it to be. The estate, therefore, is the world of the future and the hiding ground of the true Elites. It is capitalism perfected.

JWL’s adventure here is where he will learn of the nuances of this world and how he can best make himself as an individual within it. Given he will be meeting Mason and Dixon here as well, they will similarly be observing these phenomena.

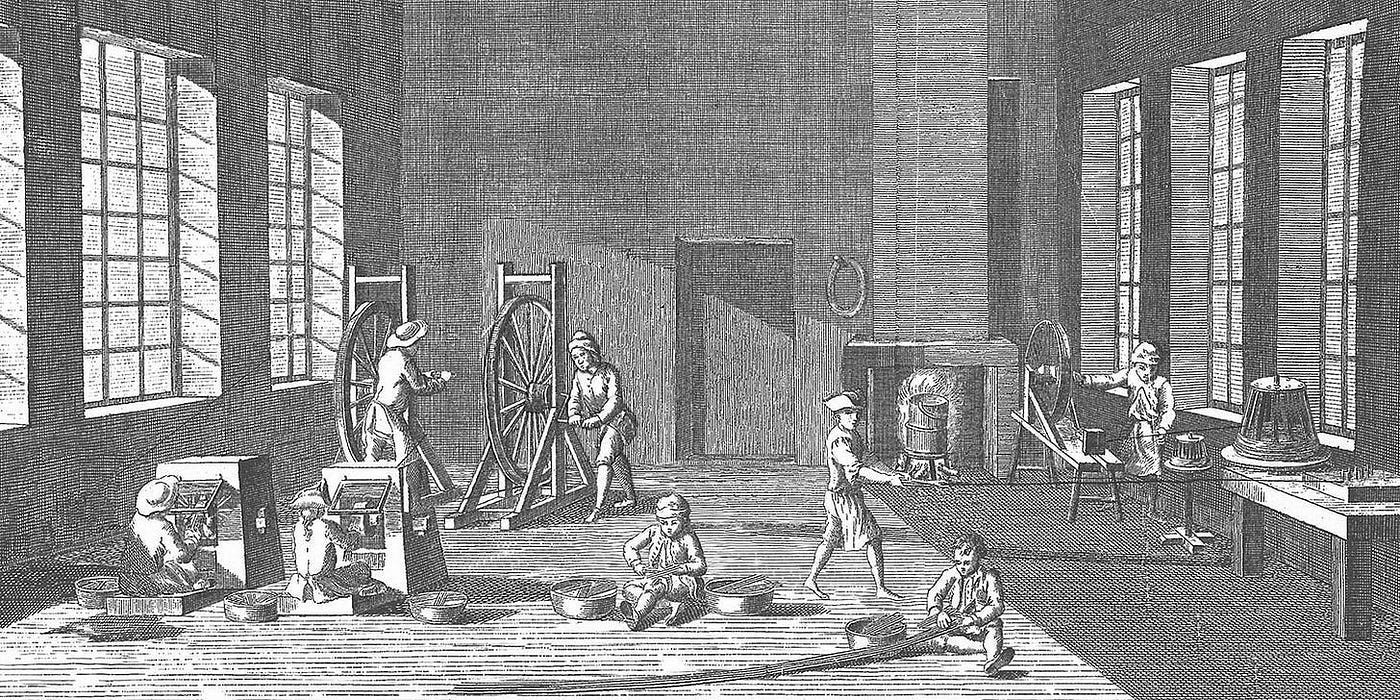

One’s first journey into a world as complex and impossible to parse as capitalism itself requires a guide. Hence, “In [JWL’s] first Trips out, he engag’d local Guides, who kept to the shadows and did not speak” (411). Similarly, we will consult silent guides — be they Marx in his Das Kapital or Smith in his Wealth of Nations — to give us insight into the many cogs (intentional, accidental, or coincidental) that lead to the end system we see today. The guide which JWL would seek to explain the inner workings of the “Iron-Plantation of Lord and Lady Lepton” (411) would likely be, though it was not written at this time, that of Adam Smith’s. Through this, he (or we) would see an Iron-Plantation being the perfect allegory for modern capitalist labor systems. It, literally, was a place where ‘pig iron’ was produced, pig iron being a crude form of iron that would be used to produce iron products and eventually, in the 19th-century, used as the intermediary good in the production of steel. Iron-plantations notoriously used a combination of slaves, indentured servants, ‘skilled’ workers, and a combination of other merchants, tradesmen, and ‘masters.’ Adam Smith would be far less critical to this form of exploitation, hence why JWL would prefer seeking out a guide such as that.

All production today requires the same forms of labor, be they ‘slaves’ who now work within prison systems or in countries with far less stringent labor laws which imperialist nations exploit, ‘indentured servants’ similar to wage-slaves who are beholden to capital in order to pay bills and keep their apartments, ‘skilled workers’ like engineers who have been led to believe their specialization places them in realms above these others while they (in reality) are still subject to the same system, ‘tradesmen’ whose learned craft creates the products which are used in this specific industry being described, or ‘merchants’ who are middle men between all of these entities. And through all these forms of labor and trade, “Iron in an hundred shapes was being produced, exactly to plan” while “noxious smokes and gases were being vented someplace distant, invisible” (411). The production of such a product in these enormous quantities, just as it does today, produces amounts of pollution never before seen. In the fantasy world of Lord Lepton’s estate, these gases can be vented of into realms that do not affect those like Lepton himself — just to realms of those who can suffer the consequences without the power to do anything about it.

But in our world, things are much simpler. We do not need to worry about metaphors of capitalism; instead, we merely build these facilities in districts the average person will never see: poor and destitute parts of town where the pollutants will cloud the lungs of undesirables, areas where cancer rates will skyrocket — largely undetected — but which neither you nor I will ever drive through given they are the part of the world we are told never to visit, or are the part of the city which paths do not often lead unless one knows where to go. Places distant — invisible.

Those who do understand all of these implications would find the system indescribably evil. But many do not. Those like J. Wade LeSpark have “felt the invisible Grasp of the Magnetic” (412) and could not tear themselves from it. They had something to sell and would exploit that system in order to make their mark.

Reverend Cherrycoke has faith that, if one could understand this system in its entirety, not even the evilest of souls would allow its existence to continue. He believes that, to JWL,

“What is not visible in his rendering […] is the Negro Slavery that goes on making such no doubt exquisite moments possible,— the inhuman ill-usage, the careless abundance of pain inflicted, the unpric’d Coercion necessary to yearly Profits beyond the projectings even of proud Satan” (412).

But JWL does understand this. We know he does. Just as capitalists know today that slave labor in prisons build many a commodity. Just as slave labor during WWII built rockets and weapons of war to kill the families of those building these weapons.3 This has always been a part of the system since its very inception, and the denial of this knowledge is tantamount to pure ignorance — ignorant being something that we know JWL is not. He has consulted those same guides that many fighting against this system have consulted but has come to the conclusion that exploiting such a thing to better his own position a-hundred-fold is more desirable than working to make the world two-fold better for all.

Cherrycoke likely has these outstanding beliefs because “he’s enjoying the fruits of the LeSpark family business and the profits it’s built through exploitation” (Biebel, 172).4 Whether he knows it or not, his profit off of another man’s exploitation will render him more amenable to forgetting the horrors of what led to his prospering. He (maybe you, even) would be willing to say that he was not aware of the true horror which led to his position since he had no part in it. Nobody wants to move further down the Great Chain, so why would one admit that?

The perspective switches over to Mason and Dixon arriving at Lord Lepton’s estate where they would eventually meet J. Wade LeSpark (though this will not happen until next chapter).5 The two surveyors come across what appears to be a mere cabin. Yet when they enter, it is far larger (or appears to be far larger) on the inside than on the outside (similar to the carriage in which Cherrycoke rode to Knockwood’s Inn in 2.35). This estate’s illusory size is purposeful, appearing to bear little importance while, in reality, holding all the secrets of future history. The reference to the carriage brings back that allegory to a historical path forward in that it represented “an intricate Connexion of precise Analytickal curves, some bearing loads, others merely decorative, still others serving as Cam-Surfaces guiding the motions of other Parts” (2.35, pg. 354). What one could see on the surface of the carriage, of Lepton’s estate, or of history itself was one thing; delving within shows its reality of far-more-challenging-to-parse minutiae. Nonetheless, these minutiae and complexities are hidden away so that those who are willing to do the work to comprehend them do not get that chance. Thus, Lepton’s estate was hidden so the historical path forward for the capitalist system (discussed above) would not be discovered too early. Mason and Dixon, however, by chance or because they were meant to, stumbled across it in the woods. The first thing which they saw inside of it, lit by crystal chandeliers, was the Plafond (a painting upon the ceiling) “depicting not the wing’d beings of Heaven, but rather the Denizens of Hell, and quite busy at their Pleasures, too” (412). This system and this history are run not by angels in heaven nor devils in hell, but devils in heaven — another illusion meant to confuse. For, if some person, creature, or being came from God’s territory, then it must have good intentions; it must be holy, right? But it is a demon disguised as an angel. It is a man who comes from an ostensible place of goodness, but whose intentions are built into what he really is — a good-hearted CEO, a hospital administrator who truly cares about patient outcomes, a billionaire who came from nothing, a capitalist who believes in helping the people.

While they want to leave, knowing something is off, they must stay for their own safety from the dark of night. Music calls them onward, signifying “that they have entered something long in Progress, existing without them, not for their Benefit, nor even their Attention” (413). The surveyors may very well have been called to America to continue this project just as they arrived at the estate, but the project itself has been going on in the background for far longer than they have been aware of it — ‘not for their Benefit,’ but for that of the inhabitants of this estate. And speaking of these inhabitants, while viewing the elaborate art and architecture of this estate, they are welcomed in by an unnamed figure who draws them into the grand ballroom where many are currently dancing to the music they had heard.

While the both of them realize something is off about all of this and that they wish to escape, they similarly understand that if they do not pay respects to the hostess of this event — in other words, if they do not submit themselves to the powers that be — then in the end, they will be “expell’d from the Province,” or at best, “Sheriffs will be instructed to make [their] lives even more difficult” (414).

The first to recognize them in this room is one of Dixon’s ‘Calvert connections’ — the Calverts, again, being the family who had held claim over Maryland for generations since 1632 and would still possess it until America claimed independence from England in 1776. Dixon had been accused of having connections with this family (2.27, pg. 268), and now it seems that this may be truer than it was only once inferred to be.6 Nonetheless, this Calvert agent warns the surveyors that they are in a place they should not be, and that if they were to stay, they must acclimate to the scene which they are in, else they will fall to the “race who not only devour[s] Astronomers as a matter of habitual diet, but may also make of them vile miniature ‘Sandwiches’ […] and then forget to eat them” (414). The attendees of this ball — of this estate — would consume them in a reversal of the common eat-the-rich sentiment, doing so in order to keep the secrets of the plantation within said plantation while turning them into that common symbol of the ‘Sandwich’ which has time and time again been used to represent a system that could hopefully change but would only ever become another form of what it originally was. However, they would then ‘forget to eat them.’ In summary, if Mason and Dixon did not relent and give in to the system and if they did not keep the secrets secret, they would be relieved of their positions, still remaining the same persons who they originally were, but without any hope for anything more. They would be Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, men whose names would not go down in history and who would struggle like those laborers employed at the Iron-Plantation. And in the end, at least they (or you?) would not be literally consumed and killed, for you were not truly a threat, merely an inconvenience. For now, at least. The reason for Calvert’s warning is that he has connections with these men and reasons to have them in his favor, for if he remains in their good graces, then Maryland’s territory could easily grow according to his wishes.

Lady Lepton, the hostess, makes her appearance. While the Calvert agent tried to remind them to remember their place, Dixon immediately fails. Surprisingly, he is not turned into a sandwich. His reaction to Lady Lepton is unexpected. Dixon, unable to help himself, excitedly tells Lady Lepton that he recalls a time “years ago at Raby Castle,7 where [she] came to visit” (415) when the two of them were still children. Dixon, upon her visit, was enraptured by her beauty and the elegance of her dress. Surprisingly, Lady Lepton did not respond derogatorily to this man far below her but instead, despite her entourage telling her to ignore such a worthless child back then, she now tells him that “after all these years, I still remember you” (415).

Through this conversation, an orchestra made of slaves plays the music for the ballroom dancers. The “melody-maddened Iron-Nabob [Lord Lepton] has searched them out, a Harpsichord Virtuoso from New Orleans, a New-York Viol-Master, Pipers direct from the Forests of Africa” (415). The band is reminiscent of the singers of the War’s Evensong, sung in the English Church during the end of WWII, listened to by Roger Mexico and Jessica Swanlake (Gravity’s Rainbow, 1.16). That chorus was led by a man from Kingston, Jamaica and was also populated by members of various races and religions. Similarly, men from all over were brought here, now making up the chorus which in Mason and Dixon’s time was forced to entertain the Elites, and in Roger and Jessica’s time were brought for reasons that had become inexplicable because of all of the complexities of the wartime state.

In the same way, the musical instruments that the band plays upon have been brought from all over: “The string instruments are from workshops in Cremona, the winds from France, and the music they are playing [is] […] perhaps in the unashamed prevalence of British modality,— that is, Phrygioid, if not Phrygian” (415). Not only are the instruments a part of imperialist trade just as the people are, but the art itself is. For this mode in which they are playing is classified as a British modality, when in fact, “The Phrygian mode is a minor-key musical mode going back to the Greeks. ‘Phrygioid’ implies an imitative quality, suggesting that the music is not quite ‘the real deal,’ perhaps because it’s been purchased, smoothed over, commodified” (Biebel, 173). We have already seen the capitalist system, viewed through the lens of Lepton’s estate, produce commodities. But here, capitalism will do the same to art. It will enslave black and brown souls who can produce music of an incomparable emotional level. It will utilize imperialism to gather instruments, sounds, tones, and all the like from around the globe. And it will steal modalities and keys, claiming them as originals. All this to produce songs to entertain those like the Elites or anyone who will pay enough to be entertained by them. Whoever makes these purchases, however, does not matter. For the money will enter the pockets of these Elites one way or the other.

The focus returns to Dixon and Lady Lepton. Dixon remembers their meeting. He recalls that “His Great-Uncle George, believing her a Witch, cast at young Jeremiah looks of sorrow and reproach” (416). Coming from a heavily working-class family in rural Britain, his family did not trust her — nor did they condone Dixon’s obsession with her. Interestingly, she did not exhibit fully Elite class tendencies (at least those that would be expected during the time period); Dixon, spying on her, saw her “kissing one of the Chamber-Maids” (416). Yet, while she may have been an atypical Elite, she still intended to further climb the social ladder. Thus, it should be no surprise that she sought out a man such as Lord Lepton — a man who had gained wealth through gambling and gaming (stock trading?), refusing to pay his debts, taking a new name and traveling to America where he would use his position of privilege, wealth, and power in order to enslave those of a lower class than him, to destroy the land and the earth itself so to extract its contents, and, by the hands of his slaves, to warp it into a form that could be bought and sold on markets innumerable. He was the classic capitalist, coming from a position not necessarily of destitution nor of pure Elite privilege, but nonetheless making use of the privilege he did possess and becoming one of those Elites. With this, the woman who existed previous to being known as Lady Lepton became the ‘Chatelaine of Lepton Castle.’ And Lord Lepton went back to England to bring her here, to America.

Speaking of the Devil (literally), Lord Lepton finally emerges, not seeming to like the presence of Mason and Dixon all too much. He prods them with questions, eventually bringing up the ‘Great Chain of Being’: a hierarchical chain that has been referenced before, alluding to hegemonic power structures from top to bottom, but here also referencing those of Godliness or angelic nature being above those of Elite men and so on downward to those playing the music for them all. Biebel states that this chain “is linear, not circular, and is not a ladder. It can’t be climbed” (Biebel, 173). The purpose of a chain, largely, is to tether one end to another — he who is the most important to they who hold one to the mere decking. One chain link always leads to the other and none can ever switch place, nor will the deck ever gain importance over the boat, the yacht, or whatever is being tethered that day.

Captain Dasp, the Calvert agent, theorizes that this chain may be something different: “Perhaps it is a Helixxx,” (417) referencing the structure of a DNA double-helix, thus placing the great chain into something as biologically natural as one’s genetic code, or if one were to take it further, a eugenicist approach to power. The deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) structure, since its discovery, has been used to give eugenic power to those with specific character traits, be they skin, hair, eye color, height, or any other so-called ‘desirable’ features. Hence, Lord Lepton’s response to the helix as a different form of the Great Chain: “Yes!,” (418) and his sexual reaction on top of that. Any Elite would find immense orgasmic relief in the realization that power could be eugenically based.

Dixon, however, claims that he sees power to exist not as the vertical Great Chain, nor as a helical structure, but as a ‘horizontal Chain,’ similar to the one which he and Mason have been using in order to measure the lengths of the line they are mapping. And he too is correct. Power stems from borders; those on one side immediately bear more power than those on the other dependent on the more common chains. For example, if those on the south side of the border possessed more desirable genetic traits than those on the north, they would also possess more power. Or, if those on the north side had more wealth and political influence than those on the south, they similarly would possess more power. All of these realms were based in innumerable bases, leading to the fact that in order to be an Elite, you had to be born in the right place, at the right time, to the right family, with the right traits. Of course, exceptions could be made; someone like Elon Musk, for instance, is clearly not the eugenic masterpiece that the Elite class would like to claim as their own. But given he works hard enough to maintain the Elite dominance over the lower classes, they will accept him for now.

Lady Lepton reminds Dixon of coal, telling him that the end state of this project involves that substance. She knows of the evils that are coming from the system that those like her husband are attempting to instill, but although “Life for her in these forests has never prov’d altogether exhilarating […] [and] altho’ like her husband she may laugh at anything” it is very clear that she “married him for his Membership in that infamous Medmenham Circle known as the Hellfire Club” (418). Lady Lepton may be aware of the system which her husband is allowing to persist, but she has married him for security, comfort, and wealth. What she may not be aware of is the nefarious deeds that really stem from something such as the Hellfire Club (explored largely in 1.11), though if she did, it is likely that such a thing would not lead her to rethink her decision to seek comfort in the position she has reached.

Captain Dasp reflects on the secrets which someone like Lady Lepton could be hiding within her skirt — inferring that men in power question what these women are really seeking: could it be something they are trying to sell such as “contraband Tea,” an alternative motive such as “fruits of Espionage,” an actual desire for something more in this world like “a moderate-sized Lover,” or even something to send this whole world to hell such as “a Bomb” (419). Lady Lepton, maybe realizing they are onto her or maybe because she is simply confused as to why they believe she has evoked distrust, tries to convince them otherwise. She states that the only thing she could possibly hide is something as simple as a ‘key’ or a ‘love-note.’ And, stereotypically enough, Lord Lepton not only falls for this trap, but continues the incredibly gender normative claim that ‘skirts’ “are for ripping, and there is an end upon it” (419). Sometimes, men as powerful as Lord Lepton fall back into that simplistic masculine state, unable to view anyone outside of their own lived experience as a complex, multi-faceted person like they believe themselves to be.

While Mason, Dixon, Lord and Lady Lepton, and the Calvert agent Captain Dasp have this odd conversation in the middle of a ball room, African slaves walk around giving out hors d’œuvres — slaves of the same sort that are playing the music. Lord Lepton’s estate — and thus the capitalist system in general — relies on the abuse, subjugation, and enslavement of this people. While one approaches Dixon with some food, “She seems to know him [and] […] [f]or a frightening moment, he seems to know her” (419). Could it be Austra? It seems impossible that it would not be, for which other African woman would know Dixon and which other would Dixon know? It does not seem likely that Dixon would have known one well before we joined him in his story, and throughout the time in which we have followed him, we have not met another who would seem like someone he would recall so readily. Thus, we can assume it was her. She has been traded however many times, from the hands of Cornelius Vroom and his Dutch colonial family in Cape Town, South Africa — as both a slave for manual and sexual slavery — to here, as a slave of the purest form of capitalism.

Mason comes to believe that Captain Dasp was most definitely a spy. He recalls “The Peace of Paris,” (420) a time where “France ced[ed] territory to Britain” (Biebel, 114) during the 1763 Treaty of Paris — something similar to the infighting between Spanish and French Elites during the War of Jenkins’ Ear. But what could Mason’s realization really do in all of this chaos? A single man, spying on another powerful nation when slaves and all other forms of oppression run rampant, is just a single man. What can he really achieve in the grand scheme of these horrors?

As always, in these realms of purely Elite fraternization, Stanley Kubrick’s film, Eyes Wide Shut, emerges. At Lepton’s hidden estate, “Gongs, each tun’d to a different Pitch, are being bash’d. ‘At last,’ mumble several of the Guests as they make speed toward yet another Wing of Castle Lepton” (420). Those Elites who have attended this party finally get their one and only wish — “Here is a Paradise of Chance” (421). It is a realm which they all have laid stakes to enter, betting on red or black on the E-O wheel (the roulette wheel), and other forms such as “Billiards and Baccarat, Bezique and Games whose Knaves and Queens live” (421). These gambling tables, in which men who desired sexual taboos to replace their many already fulfilled desires, are “the wide World, lands and seas” (421). This realm of capital and the perverse functions which it will necessitate will soon become everything that we know, and yet it will still appear — from the outside, at least — as a small cabin in the woods which seems nothing more important than a dying tree, or a carriage that travels down on another trail, heading toward an inn, to rest. It is run by a man like Lord Lepton, whose name references those charges which only interact with other charges that we will never feel — because they make up the world. In the system which we live, they hold things entirely together, so universal that they are invisible, never interacting with the things we can actually see.

But deep inside, if one were willing to look, takes place horrors beyond your imagination, all fueled by a system which is so common that we deem it to be the natural way of the world.

Up Next: Part 2, Chapter 42

This is the first truly explicit interruption of Cherrycoke’s story. From what we know, Cherrycoke has told everything up until this chapter.

Just because I find elementary particles interesting, I’m going to briefly catalogue what lies within the other subcategories. (Some of this does actually tie back into Mason & Dixon or other literary works, but feel free to skip it if it doesn’t interest you).

Within the quark (and antiquark) family, which is another type of fermion like the lepton, lie six different ‘flavors’ of quark (plus six anti-versions): the up, down, charm, strange, top, and bottom quark, all of which combine in some formation to create different hadrons of which there are two subcategories: baryons and mesons. Baryons, made of three quarks, include a large number of particles, but our most common are protons (made of two up and one down quark) and neutrons (made of one up and two down quarks). Mesons are made of equal numbers of quarks and anti-quarks and include particles not commonly known such as pions and kaons.

Note: the name quark also comes from a quote within James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. The man who discovered the quark, Gell-Mann, named them after that word in Joyce’s fourth masterpiece, taking it from the quote, “— Three quarks for Muster Mark! / Sure he hasn’t got much of a bark / And sure any he has it’s all beside the mark” (Finnegans Wake, 2.4, pg. 383).

Under the boson family (entirely separate from the fermions) lies two other subcategories: gauge bosons and scalar bosons. Gauge bosons include the photon (a massless particle) which is the particle that makes up visible light and other electromagnetic radiation like radio or gamma rays, W and Z bosons which I have zero knowledge of, gluons (another massless particle) that acts as a sort of glue that helps bind quarks to each other which means they also exist within protons and neutrons, and gravitons (also massless) which are a theoretical particle that would make up gravity if we could observe them. Under the subcategory of scalar bosons is just the Higgs boson — also called the Higgs particle or the God particle. The Higgs boson was partially discussed in 1.6 with the boatswain, Mr. Higgs. He, like the Higgs boson, was something that was never really seen unless one looked specifically for it/him, but without its/his existence, none of the other particles would be able to function.

Sorry for the mildly pointless digression, but I find this stuff incredibly fascinating. Plus, I’m sure Pynchon would want us all to know it anyway.

Joyce, James, and John Bishop. Finnegans Wake. Penguin Books, 1999.

Pynchon explores the prisoners of the holocaust building these weapons frequently in Gravity’s Rainbow such as the prison labor in the Mittelwerke (Gravity’s Rainbow, 2.2).

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.

It is also not made clear whether or not Cherrycoke took over telling the story in this section, but given the stylistic difference, it seems like he has.

Also, it is important to note that when Dolly warned Dixon about Lord Lepton back in the coffee shop (in 2.30), she also, at the same time, discussed the Calverts with him in the same conversation (2.30, pg. 301).

Raby Castle (and Lady Lepton) will come up again in about a dozen chapters (2.52). Remember it for a specific comparison there.