Mason & Dixon - Part 2 - Chapter 40: Prescriptive Ideologies

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 2 - Chapter 40: Eighteenth-Century Manhattan, Alternative Aesthetics, Brooklyn, the Sons of Liberty, Textbook Marxism, Fair and Foul, Corinthians

At the same time as Dixon began his travels southward to the coming Confederate states (2.39), Mason traveled north to the one-day bastion of liberalism, New York City. While this would immediately, on the surface level, appear the exact opposite of where Dixon travelled, the first thing that he saw on the Sky-line was “the Trinity Church, at the head of Wall-Street” (399). While certain practices and political beliefs are objectively better in these liberal bastions, the fact remains that the cities are still built upon the worship of capital and trade.1 We will soon meet a group that represents the desires of this type of ideology while enacting more of the same.

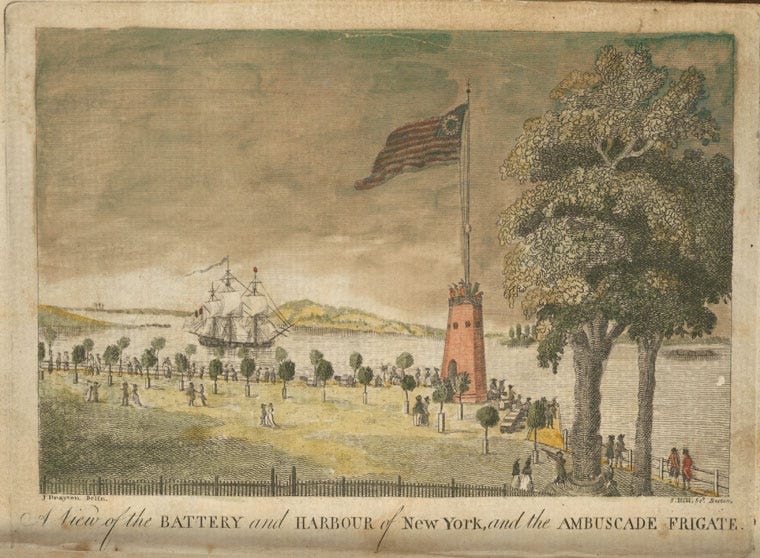

While here in New York, Mason is constantly told, “The Battery’s the spot to be” (399). On the most southern tip on the island of Manhattan lies this so-called ‘Battery’ — something that today is just a park, but at the time of Mason and Dixon was a fortified base with artillery batteries lining it. The ‘Battery’ and its surrounding environs were originally home to the Lenape people who were killed or driven off this land. The Dutch then built the fortification in 1626 and controlled it until the English took it over in 1664. It was used in one of the first wars between colonizers, King William’s War (a branch of the Nine Years War), which was fought between New England and New France from 1688-1697. Since 1697, up until Mason and Dixon’s current time, the batteries lining the shore were not in use and would not be in use again until the Revolutionary War of 1776. And today, as stated, it is a park that bears the same name the English granted it. Why is this the ‘place to be’?

Its past, present, and future give the answer. In Mason’s time, it was the point that would soon be used to defend the country from ‘foreign’ invaders. These invaders are the exact people who those like Thomas Jefferson were trying to defend themselves from: English Elites who believed they were entitled to more than these American ones. The bastion, therefore, was one of internal Elite class warfare, attempting to elevate one upper-class above the other. Today, the Battery is still remembered for this style of defense — one that separated American from English rule, leading to the land that promised ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’ Yet it was a bastion built on stolen land subsequently used to defend itself from having the land stolen back by another entity. The irony of the American project is built into this parcel which today stands as a recreational park on the shore of a city which is now the shining beacon of liberalism, likely stating its land acknowledgements and advocating for beneficial social practices while worshipping capital and placing no effort in reparations for those it had wronged in its development. It is the ‘place to be’ because it hides these evils behind the guise of ‘equality’ for all men — though ‘men’ is a broadened descriptor of the far more specific demographic it was meant to protect. It gave the visitors that warm feeling that there was only goodness which lived here.

It is here that Mason meets Amelia (also referred to as Amy), a milkmaid who he buys dinner for and then takes a ferry with to her place in Brooklyn.23 Like a modern-day goth, “Amy is dress’d from Boots to Bonnet all in different Articles of black” (400). Mason views this as one of the oddities of a far more left-wing city, not that it bothers him more than it makes him curious. But even here, such a style is deemed odd. Amy’s Uncle, for one, who lives with her in Brooklyn, is worried for her.

Alternative personal aesthetics such as goth, emo, and punk, have always been readily associated with leftist politics. Despite certain branches of these aesthetic styles attempting to co-opt the leftist association and rendering it more centrist or even right wing, any true goth/punk/etc. would disavow these branches entirely, being as hostile toward them as they would any proponent of the traditional system. Amelia, interestingly, is not only a ‘goth,’ but somewhat like a Valley Girl as well, utilizing similar speech patterns as our modern-day equivalent but replacing the excessive use of the word like with the word as. Goths and Valley Girls are highly antithetical to each other. This disparity will continue to grow and we will soon see why.

When arriving at her home, Mason meets her ‘Uncle’ — someone far younger than he expected and who likely is not actually related to her by blood. Through conversation, Mason starts piecing together even more oddities — Amelia’s name is likely a code name and the group themselves are not a family by blood but by association. It turns out that those in this house — Amelia, ‘Uncle’ AKA Captain Volcanoe, the ‘Half-Breed’ AKA Drogo, the ‘Sailor’ AKA Patsy — are a precursor to “The Sons of Liberty (an underground political organization seeking to fight British taxation in the colonies)” (Biebel, 168-169).4 This supposed revolutionary organization sought to free themselves from British rule, acting something akin to what we would today consider anarchists. Interestingly, Dixon, in Virginia, met Thomas Jefferson who was doing this exact same thing. Being here in Brooklyn, which at the time of Mason (and at the time of Pynchon’s writing of this novel), was a far more working-class borough, we can assume that this group is not one of the wealthy Manhattan Elites. Obviously, a working-class group working against Elite oppression is far more amenable than an Elite class (like Jefferson) working against other Elite class ‘oppression’; however, this does not render them free from criticism.

Before getting at why, we’ll summarize a bit more. For now, they scrutinize Mason, deeming him to be the enemy since he appears to be British — from the exact political body they are fighting against. Mason, now going by ‘M’syeer Maysong,’ must pretend to be French in order to stay in the group’s good graces. One cannot fully blame the group, for they are correct that “All the Brits want us for, is to buy their Goods” (402). Now that the colony has been formed and is being expanded without much intervention, the British seek only to profit on America in as many ways as possible. It is easy to despise the people who are solely using you for your labor and the wealth which you can create. But again, the blame here comes from white Americans toward white Brits — very little thought of class or anyone who may lay outside of the spectrum of whiteness. Very little thought on others who may be affected in entirely different, far more oppressive ways.

After Mason continues to put on his faux-French accent, the men begin to accept him, even going so far as to asking him to help repair a telescope that they have since he has also revealed himself to be an astronomer. When he goes to fix it, he sees that it is pointed at various “important commercial and military landmarks running from Manhattan down to the edge of Brooklyn5” (Biebel, 169). Mason cannot comprehend the use of this tool for something other than viewing the stars, stating that it should be pointed up at the sky rather than down on the Earth, a comment which distances himself from even the most ineffective and self-centered revolutionary action. But while here, he also hears the discussion between these ‘Sons of Liberty’ precursors, miming (even though they didn’t know it) Thomas Jefferson’s argument (2.39) about taxation without representation. Their argument, however, at least has more merit. They are asking us, ‘do you think these politicians, these Elite, these British monarchs, really have our best interests at heart?’ — “embody us? Embody us?” (404). And no, they do not. But the parallels between the white Elites and the white Preterite begin to merge. While there is clear difference in who they care for and what their goals are, neither show true benevolence toward the entirety of the human race. Only those just like them.

Captain Volcanoe — the Uncle — ironically brings up ‘Transsubstantiation,’ referencing that the body of government is meant to literally embody and become the will of the people. And Mason, understanding this irony, retorts by stating that it is more like ‘Consubstantiation’: the idea that the government and the will of the people exist besides one another but are connected symbolically and definitionally — and nothing more. With the con/trans differentiation marinating in the heads of the pre-Sons-of-Liberty, we see more of their true colors emerge: they have belief “in Parliament along the Lines of Mr. Franklin” (405). But Mason has met Benjamin Franklin. He has seen him attempt to separate him and Dixon from one another (2.27) and how Franklin has summoned the patrons of a bar to death via his play (2.29). So, he tells them that those like Franklin may not really be “working for us, not some Symbol of the People who won’t care a rat’s whisker about his Borough, who will indeed sell out his Voters for the chance to grovel his way to even a penny’s worth more Advantage in the World of Global Meddling he imagines as reality” (405). And they understand this but interpret it in alternative ways — the need to either resist against the ‘kings’ of England or to infiltrate their offices to make certain changes that they believe could alter the direction that things are heading toward.

This disparity recollects Rosa Luxemburg’s Reform or Revolution?6 While many of these members believe that inserting one of their own within the government could possibly reform policy enough to remove them from British tyranny, another one is aware that Reform can just slow down such tyranny, and only a true resistance could ever hope to stop it entirely.

To tie this whole chapter together, what we have been seeing emerge is something of the highly prescriptive modern-day leftist movement. We have begun with the contrast between a Valley Girl and a Goth, both in the character of Amelia — two entirely disparate aesthetics which infer the desire to be revolutionary while always remaining rooted in middle or upper-class white culture. Next, other than the man horrifically referred to as ‘Half-Breed,’ each member of this underground group is white. Then, the most condemning fact, their fight is only for their own white race — looking only at pure class oppression and thinking nothing of the systemic racism or sexism that has been naturalized in their world. We see this in that their goal is the exact same as Thomas Jefferson’s, where they wish to free themselves from taxation and thus see the fight stopping there — or at least seeing that as more important than any other form of liberation. However, if the Americans are free from British taxation and rule, what does that do for any other class or demographic? Does it free the slaves from their shackles? Does it create an equitable or liberated society within America itself?

Because yes, a liberated working class is one goal in revolution, but a reading of archetypal Marxist/revolutionary thought outside of a modern-context leaves plenty off the table. It ignores the fact that even if much of the naturalization of racism and other forms of bigotry directly stems from capitalism and imperialism, just getting rid of capitalism or imperialism by freeing the working class does not exactly mean that those other now naturalized ideations will disappear overnight. They are built into our world and so any philosophical framework which we base liberation on must also evolve to incorporate other forms of liberation beyond what they were defined as however many decades or centuries back. In conclusion, this group is infinitely better than those like Jefferson who seeks to free his own version of the future of the Elite class. They, too, are far better than the Manhattan liberals who may very well appear to be benevolent on the surface, but who worship capital to the highest degree and so will never possess the belief or courage to liberate anything but their own ego. However, in the end, they are the modern online Marxist — the man on Reddit who harps on reading classic theory but who refuses to reincorporate the complexities of modernity into their own philosophy.

Nonetheless, groups such as this can teach us much given reading theory, philosophy, literature, or participating in revolutionary ideology is a massive step in the right direction. For instance, Mason attempts to convince them that he is a perfectly free man, being so lucky to possess rooms which “have been included among the terms of [his] employment” (406). They remind him, teach him, that “Someone owns you, Sir. He pays for your Meals and Lodgings. He lends you out to others” (406). They teach him that he is free compared to a slave but is just subject to a form of slavery with a prefix attached — wage-slavery.

Mason refuses to acknowledge and accept this fact. He goes back to working on the telescope while Captain Volcanoe continues informing him that this movement’s various groups, one of which they are a part of, “are in Correspondence, […] as are all the Provinces one with another” (406). Biebel states that this is “A reference to Committees of Correspondence, which sought to connect early Revolutionary leaders in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, etc. via (often underground) networks of communication, including letters. There are striking similarities to the secret courier service that forms the central plot of The Crying of Lot 49” (Biebel, 170). This network within The Crying of Lot 49 was one which was given to the people by the government (analogous to the Internet or other surveillance networks) which could be used to spread this form of education or potential action, but which would always be monitored without the users knowing it. So, while those like the ‘Sons of Liberty’ have more humane intentions than those like Jefferson, the revolution which they seek is being surveilled, and any attempt to bring it beyond what the Elites intend can easily render it cut off at the source.

Amelia reveals more about the fantasy that the ‘Sons of Liberty’ posses. She states that Mason’s job in drawing the border between Pennsylvania and Maryland is hopeless; for, soon, after the revolution, “in the world that is to come, all boundaries shall be eras’d” (406). As we know today, this revolution did nothing of the sort. Borders still exist in an even more heinous version than they ever did. And this comment brings us back again to the reality of what will come from a revolution that only takes very specific, unevolved ideology into account. The ideology is a framework which must evolve with the times, or else it remains a framework at best.

Drogo and Amelia continue attempting to convince Mason that he is a slave. Marxist philosophy references wage-slavery as the modern form of slavery based on labor exploitation; however, this does not acknowledge the modern prison system (or other systems within our world) which have simply redefined slavery to maintain its legality. Mason, therefore, in this case more evolved in thought than they were due to his travels, refuses this notion. He may be a slave in the sense that they define, but having been in Cape Town and now America, there is simply no true comparison. And they are all correct, but (and I harp of this point again) none of them allow for their own philosophies to change — to evolve with the times. It is again the following of a prescriptive doctrine.

Amelia retorts, bringing up the fact that independent of the form of subjugation or regulation — be it the “rifle-butts [or] whips” (407) — it is still slavery. She will not relent. For the master of the laborer is like a master of slave — any form of organization, be it a union (like the mentioned Clothier’s ‘Association’) or literal revolution, is shut down easily with the flick of a whip or smash of a rifle-butt. And again, the prescriptive shows its limits: Mason states that “Slaves are not paid,— whereas Weavers,—” (407). And Amelia continues to push the narrative that wage-slavery is equivalent to slavery. She continues to push doctrinal philosophical thought without any form of evolution, bringing Mason to contemplate the autumn of 1756, where the wages of weavers were significantly cut.7 He recalls that not only was he not a true slave, but in terms of wage slavery, he had it easy. For yes, most of us may be wage slaves, working day-in day-out for some bourgeoise body. But while someone like Mason could run off to work for someone else with no fear, others would be subjected to the abuse of soldiers blows or to true impoverishment. All Mason would have to deal with was the disappointment of a father. To all others, he would be a class traitor, seeking better conditions in the same environs while leaving them to take the beating that should be equally distributed among them all.

Getting back on the ferry the following Wednesday morning, Patsy follows Mason to see him off. He reminds Mason that there is a potential revolution coming, perhaps hoping that Mason will attribute this war with the desires and actions of the ‘Sons of Liberty.’ But Mason, having sought out the hiding places of the Elite, knows better. He responds, saying, “They rely upon colorful Madmen and hir’d Bullies to get them thro’ the perilous places, and they blunder on. Beware them” (408). (This comment makes it likely that Patsy’s name is symbolic for a patsy — the fall man in political conspiracy). Whatever revolution may be coming will be fought not against the true Elite who are propping this system up and profiting on it, but against their underlings who they send across waters as puppets to take the blame. History books will show generals fighting generals, admirals bring their troops across dangerous waters. But while the names of men who sit back in their Empire chairs will be known, the glory of battle will be the thing students of history are told to pay most attention to. Mason ever so often defending the English, has changed his view to understand this fact. Revelations have been made to him that lead him to this point, questioning all that he has known before.

The final passage interrogates historiography as usual, combining perspectives of two different Field-Books (the Foul and Fair copies), that of the LeSparks, and that of Mason as well, all in a blended section. It catalogues Mason’s journey back down south, traversing through the Jerseys. Both copies of the Field-Book have similar stories, though the Foul Copy has some alternative entries that Mason did not wish the proprietors to see. This infers that certain thoughts or even actions of Mason’s (and Dixon’s) may not have been accurately reported. Could they have made themselves look better in the eyes of the proprietors, thus making them look worse in our eyes? Or would they have preferred themselves to look better in historical documentation, in turn making them look worse to their proprietors? Likely the former — and if that is taken to be the case, then perhaps their many missteps and complicities which we have read about (and which we will soon read more about) do not possess the same degree of complicity we once believed. Are they less complicit than we’ve made them out to be? More complicit? Or do these trivialities even matter, given there are so many of them that they may, in the end, cancel out?

Ives, J. Wade, Ethelmer, Euphrenia, and Cherrycoke all posit the oddities in this scenario. Mason seems to have changed somehow based on this trip alone, and each member has their own belief as to why, be it the influence of Christ, the Devil, or some other being. Again, as with the two versions of the Field-Book, history’s retelling is influenced from an outside source.

But Mason himself, recovering from the fall off his horse after leaving New York, looks to the Bible for answers as to what caused his change, reading “I Corinthians, in particular Chapter 15 […] to Verse 42” (409). The vital portions of the King James Version of said passage are as follows:

But God giveth it a body as it hath pleased him, and to every seed his own /

All flesh is not the same flesh: but there is one kind of flesh of men, another flesh of beasts, another of fishes, and another of birds. /

There are also celestial bodies, and bodies terrestrial: but the glory of the celestial is one, and the glory of the terrestrial is another. /

There is one glory of the sun, and another glory of the moon, and another glory of the stars: for one star differeth from another star in glory. /

So also is the resurrection of the dead. […](King James Version, I Corinthians, 15:38-42)8

‘There is one kind of flesh of men.’ Status does not determine one’s glory in the eyes of God — one could be a weaver, a rebel, a politician, a New Yorker, a Virginian, a Pennsylvanian, a Marylander, an American, a Brit. But as long as one follows the laws ordained by Him, ‘resurrection’ is equal — mankind is equal. Yet, while the ‘Sons of Liberty’ were observant and conscious of equality within some realms, they ignored the others. Mason, seeing the Quakers exiting their service, is coming to know exactly what America is to be. It is a land where God’s word is taken to mean that equality for the white man will be deemed to be equality for all — those black and brown men and women, or whomever else the white Elite deem undesirable, may as well be one of those lower tiers of ‘flesh.’ Ones whose resurrection (which in this case is synonymous with ‘liberation’) will come at a later state if ever at all. Once the ‘important’ and ‘necessary’ things are taken care of first, then we can begin focusing on the others. America is to be a country built in the antithesis of God’s word, but which will be said to follow God’s command to a tee. Therefore, the Christians and the Leftists themselves are interpreting their own doctrine in ways that most benefit them — the former purposefully misinterpreting it and the latter refusing to allow it to evolve with the times.

Rebekah, whether in spirit or in dream (and what is the difference?), helps reveal this to him. But whether or not he is honest to himself about his comprehension on how the flesh of man translates to the resurrection of man, he states that he does not comprehend it. And yet, independent of true comprehension, while he may not hold this revelation close to him, “neither does he cast away, these Lesser Revelations, saving them one by mean, insufficient one,— some unbidden, some sought and earn’d, all gathering in a small pile inside the Casket of his Hopes, against an unknown Sum, intended to purchase his Salvation” (409). He has piled the revelations up one by one, beginning at Cape Town and with each passing epiphany — ignored or perceived, misunderstood or not. They sit with him inside this ‘Casket of his Hopes,’ waiting to be unpacked so to eventually reveal the true epiphany which he seeks, relieving him of complicity and leading him to salvation.

But nonetheless, he waits.

Up Next: Part 2, Chapter 41

Remember: we have separated Mason and Dixon to see how they would react to specific parts of America without the bias of being with each other. Dixon, last chapter, went to the soon-to-be Confederate states (2.39) and here Mason travels to the liberal bastion of the Union (2.40). Later in Part 2, they will do the same thing but reverse territories.

The novel states that they go to Long Island which typically is associated with the very wealthy eastern portions of Long Island; however, Brooklyn is technically a part of Long Island, and it is revealed in another page or so that this is where they ended up after the ferry ride.

Also, please note that much of the coming post will be summary and light analysis. But I will get to the point once Amelia and the group whom she lives with is fully explored.

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.

Biebel makes this connection based on the description that Mason makes in the novel.

Luxemburg, Rosa. Reform or Revolution? New York, Three Arrows Press, 1899.

This is known as the Weavers’ Rebellion, a much-forgotten historical event which will be discussed at further length later in this novel (in 2.52).

The Bible. Authorized King James Version with Apocrypha, Oxford World’s Classics, 1997.