Gravity's Rainbow - Part 2 - Chapter 4: Infernal Repentance

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 2 - Chapter 4: Brigadier Pudding's Trials and Domina Nocturna

Pointsman muses on how responses to our conditions and the stimuli around us change as we age. He is in The White Visitation, at a meeting between members of the Slothrop group discussing Brigadier Pudding’s general absence recently. Back in Part 1: Chapter 12, Pudding was known to perform his daily briefings — a series of seemingly unrelated, unimportant ramblings from topics such as “recipes for preparing beets in a hundred tasty ways” and “then perhaps a lengthy recitation of all his funding difficulties” (80). He was also characterized to be a part of the old guard: a one-time high ranking official in the pre-WWII state, where his job was truly what it was written down to be — to command and control small or large squadrons of soldiers, to receive and enact orders of his higher ups, and to follow the general chain of command.1 Hence, his speeches consisting of one-track topics and the ability to appreciate something far simpler than whatever may be going on at The White Visitation now that he was brought on to be its leader. But now these briefings, and Pudding’s presence itself, have quieted down.

The group itself seems to be on edge, perhaps slightly due to this loss of the old guard — the dissolving nature of a world they all once knew, and knew well — or perhaps because, as they outright state, Slothrop really is getting the better of them all: he’s “‘knocked out Dodson-Truck and [Katje] in one day!’” (227). But the one person who does not seem in the least bit worried is one of the personifications of the new guard: Pointsman, for he realizes that there is no point in worrying about some connecting life force. This is all run on the concept of bureaucracy, and worrying about these human factors will lead him nowhere. He must perfect his use of the system — make it so no single person, not even an entire force of people, can uproot his plan. And his first instance of perfecting this idea is the removal of Pudding: “‘we have made arrangements with him. The details aren’t important’” (228).

Of course, they are not important in this new world. There is too much occurring to ever focus on that one detail that may reveal something profound. So, instead of pursuing this thread, every member of the Slothrop group becomes distracted by some other thread — the Mossmoon issue, episodes of hysteria, the desire for whisky or sleep. Webley Silvernail — the man who showed the film of Katje to Grigori the octopus (also in Part 1: Chapter 12) remains behind to observe the rats and dogs for a moment and realizes that the labs they are all working in are analogous to the mazes they have subjected the rats to. They have conditioned those below them to condition those below them in an ever-descending stream, until all people and creatures on Earth serve Their purpose, until “Nothing’s left in Pavlovia, But the maze, and the game. . . .” (230). Silvernail even contemplates releasing them for a moment to break this chain but realizes that because of their ignorance they may be the safest, the most free, of us all.

Brigadier Pudding, though largely absent from his usual roles, is not all together gone. He still lives here at the Visitation but has a new routine. Every so often, he is sent, late at night, through a series of passages and rooms. The guards allow him to pass by unmolested, beginning Pudding’s symbolic descent into hell, and the World’s transference into the hands of Pointsman.2

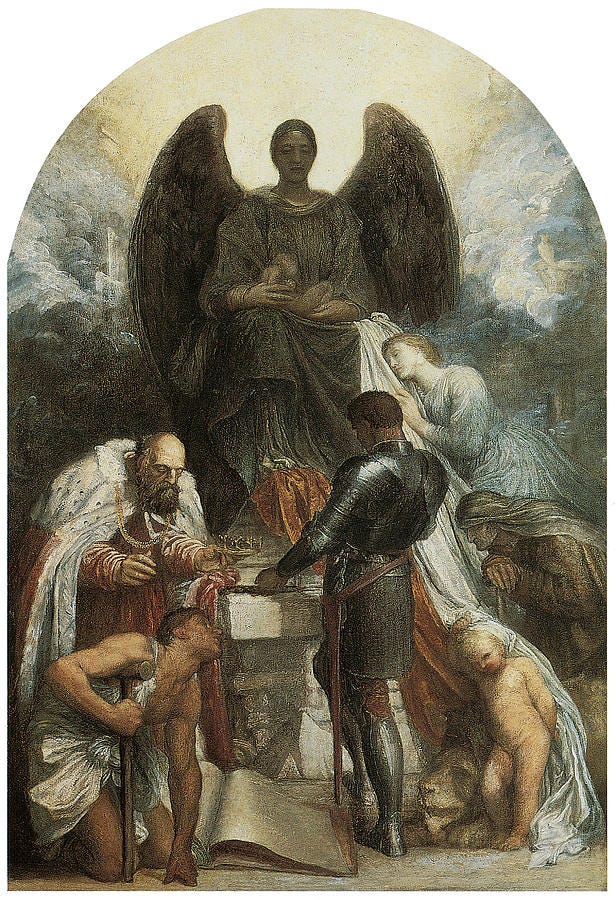

Certain Jewish mystical texts (in this case, the Merkabah) state that the ascent from the Earthly realm to the throne of God — in order to achieve redemption — takes one through seven antechambers, each one possessing a test to deem one’s worthiness of entrance. These tests chronologically are ones of devotion, purity, sincerity, and then more specifically, becoming whole with God, being holy before God, the speaking of the Trisagion3, and finally, the fear and trembling before Him. For his redemption, Pudding, however, makes a descent, where each trial is a juxtaposition of the Kabbalistic trials. These rooms are introduced by Metatron — a human become angel and guardian of the throne — whose voice is not near, but in some distant, unseen room, ominously calling to Pudding.

The first room holds “a hypodermic outfit […] left lying on a table,” (231) marking Pudding’s addiction as opposed to his devotion. In the second, a coffee tin sits on a table, Savarin brand, renamed now to Severin after a depraved character in the novel Venus in Furs, thus juxtaposing purity with depravity. The third holds case histories and “an open copy of Krafft-Ebing[’s]” (232) study on deviant sexual behaviors, showing the desire for scientific explanation over sincerity. “In the fourth, a human skull” (232) jeers at the idea of being one with God after death. The fifth, supposed to show one’s holiness before God, holds a Malacca cane, a symbol of subservience through authoritarian power and discipline. In the sixth, Pudding somehow envisions the corpse of a soldier he saw on the battlefield, causing him to relive the suffocating and putrid sensations of the battlefield; and, just as one may recite the Trisagion, he speaks out, “no . . . no!” with the song of the machine-gun to keep the beat: “dum diddy da da […] dum dum” (232). The final trial is hiding oneself, erect with fear, from God’s light. Pudding, erect in another sense, kneels before her — Domina Nocturna.4

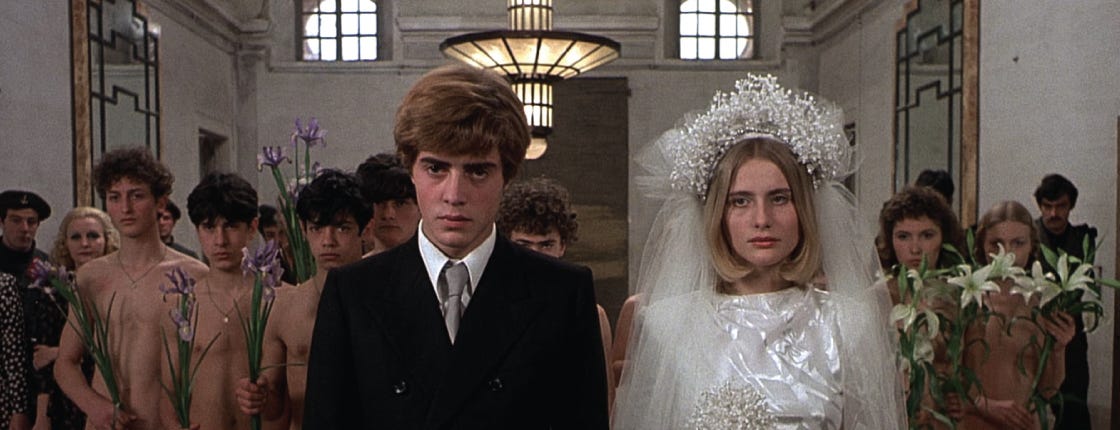

Though he may not know exactly who she is, it is Katje Borgesius, dressed in black and red, playing as if she is the one with all the power while, in reality, just as she was with Blicero, she has no true power over the Brigadier. Pudding worships her, bends his knees, pledges his service, and yet she urges him on as if she wants to get this over with. She “tries to keep her hands still” (233). She was a sex slave to Blicero, told to give into Slothrop’s advances, and is now forced to play the most heinous of sexual roles. It begins with the kissing of leather, and then he gives her the offering of a memory. This offering reveals that he has seen Domina Nocturna far in his past — not Katje playing the figure, but the occult figure itself — during the first war, where she stood in No-Man’s Land lording over the dead — where she (in his offered memory) was sung as the bride of a legion who was slaughtered at Badajoz. Through these offerings, she (and Pointsman, by proxy) is forcing Pudding to relive the most horrifying moments on the battlefield. These moments have now become that thing he must pass through the seven trials for — to achieve redemption in his own eyes and in the eyes of God.

The trial to achieve redemption, to achieve some forgiveness for the sins he feels his immense guilt for, has only begun: “‘Time for pain now, Brigadier’” (234). The pain is standard sado-masochism at first, with twelve lashes of the cane — possibly the same Malacca cane that symbolized subservience through power and discipline. But then things proceed to the most base levels of subjugation as Pudding is forced to drink her piss and, literally, eat her shit. And as he consumes it, “he is thinking, he’s sorry, he can’t help it, thinking of a Negro’s penis” (235). This symbolic vision to Pudding, an elderly white man living in the mid-20th century, would likely be the most entirely degrading act he could perform. And after it is all complete — after he has consumed every last bit of her expulsion — he is forced to leave, crying, to consume his broth and pills. He, the old Western form of war, has now been subjected to the new state of things. For now, though, he is at least kept alive, even if there is no hope that he can ever return to the fore.

Hope you… enjoyed (?) that chapter! Despite how disgusting it is, it’s really incredible how well it is written and how much symbolic and thematic content is back within it. Next week we will cover Chapter 5 of Part 2!

This is clearly a gross reduction of the complexity and nefarious nature of WWI officers and WWI strategy, but the point is that things were far easier to comprehend at a literal, surface level before WWII.

Note: I genuinely write 98% of these write-ups from my own personal analyses, rarely using outside sources since I think many of them either get it wrong or at least don’t align with my own interests in what this book is about. Here, however, I will largely attribute my thoughts to Weisenburger’s A Gravity's Rainbow Companion (2006) since I am not well read in Kabbalistic works myself and since the symbolism in this passage is impossible to understand otherwise.

An ancient hymn, invoking the holiness of God.

For parts of this paragraph and the previous:

Weisenburger, Stephen. A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion: Sources and Contexts for Pynchon’s Novel. 2nd ed., University of Georgia Press, 2006, pp. 122-123.

that certainly is a memorable chapter.

What was the Trembler Pudding finds, that part confused me!