Mason & Dixon - Part 2 - Chapter 39: Hypernormalization

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 2 - Chapter 39: Last Night at the Inn, Dixon Goes South, Williamsburg, Thomas Jefferson, Fighting for Urania, Back North, Blindness

Dixon begins by saying, “All right then, if tha really want to know what I think,” (391) which recalls from Gravity’s Rainbow, Miklos Thanatz’s “You will want cause and effect. All right,” (Gravity’s Rainbow, 4.5, pg. 663). In that novel, it was Pynchon’s response to the reader’s likely question, ‘what does this all mean?’ But as we’ve learned here, there is no such thing as pure cause and effect — no way that a single event can occur and proceed down an analyzable path. We must peel things apart and decipher them one by one, just as we will do with our astronomers in this chapter and the next (2.39 & 2.40). In this chapter we will see Dixon moving south (to the eventual Confederate side of the line) and next chapter we will see Mason move north (to the eventual union side). Much later in Part 2 we will also see Dixon travel north (2.57) and Mason travel south (2.58). Using this method, Pynchon can start to get down to more true cause and effect; separating the layers that are possible to separate; removing variables and potentially clashing personalities; removing the psychological need to please the other astronomer or to act a certain way when another is present. So just like we saw a difference in Thanatz when he was no longer in the presence of Erdmann or the rest of the Elite on the Anubis, we will be able to see how our characters in this novel would actually react to different facets of America.

What could separate them here though? Why would they need to do such a thing? They seem to have been getting along just fine. Well, for the past three chapters (2.36, 2.37, & 2.38) we have not really seen much of them except for minor interjections. But the involuntary snowy imprisonment has caused tensions to rise, and we now see them here arguing, Dixon prodding at Mason for “Not […] seeking another [partner]” (391) now that his wife, and much time since, has passed. While Mason knows (having been told this before by Dixon) that there is no ill intent, its veracity does bother him. Why can’t he move on? he probably asks himself. Then, Dixon, who has become quite rotund during their stay within Knockwood’s Inn, begins to make comparisons between the pleasure of indulging in foods to that of women. And this is too much for Mason. While the both of them have become used to the idea of unrestrained consumption and global markets, Mason has had Rebekah as a linchpin for his search for the spiritual realm in an ever increasingly material world. Thus, Dixon’s comparison between women and food sets him off. Rebekah, to Mason, is immaterial — she is his one spiritual light leading him onward. Because of Dixon’s comment, “by the time the Snow abates […] the Surveyors [have] decided thereafter to Journey separately, one north and one south, to see the country” (393).

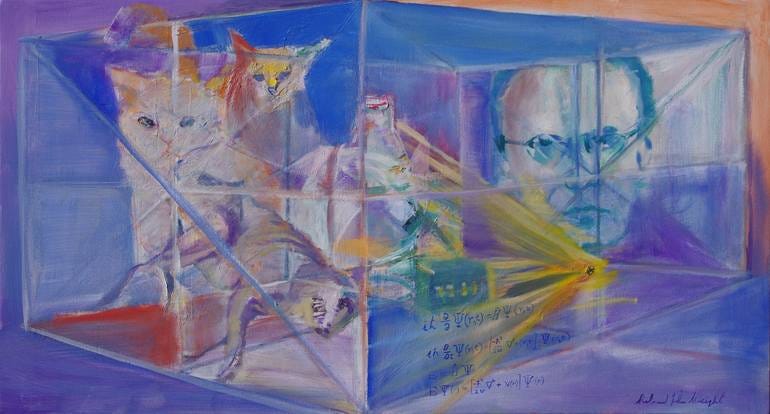

Cherrycoke interjects, stating that “with no indication in the Field-Book of where [Dixon] went or stopp’d, let us assume that he went first to Annapolis” (393). His journey, unlike Mason’s journey north next chapter (2.40), was uncatalogued. Hence, all that we know about it is largely fabricated. Ives LeSpark refuses to let this hypothesizing slide. The victors write history; we cannot let those like Cherrycoke craft his own ideas, metaphors, analogies, or layers into what we know as the factual truth. However, though he doesn’t say it, Ives’ issue is not one of ‘assumption.’ It is who is doing the assuming, for he very well knows that much of history is not factual or at least has no one-to-one basis in something like a catalog or Field-log. So, to alleviate this fear, Cherrycoke brilliantly posits two possible trajectories that Dixon could have taken, to which Biebel says, “[this] Recalls the ‘Schrödinger’s Cat’ thought experiment, or the idea that quantum particles can be in ‘superposition,’ existing in multiple places at once and only able to be pinned down when they collide with large enough chunks of matter” (Biebel, 165).1 Again, chains linking into other chains, carriages bigger on the inside than out, laminated pastries and Damascus steel — there is no singular truth to history. It is a blend of layers. What Ives likely does not get is how this all comes together. Cherrycoke may be admitting here that his history is incorrect and that the story he is telling could be taken onto an entirely different trajectory. So, Ives could see it as innocuous given Cherrycoke is literally admitting it is not true. But again, the point is not the factual. The point is how we interpret what occurred. It is literature versus history, spiritual versus material. We need both to understand what led us here; and Cherrycoke is presenting both. Yes, Dixon went south and we do not know much more; however, interpretations, fabrications, and thematic revelations can potentially teach the children more than they could have learned if we knew the factual.

So begins his (hi)story to the south side of the line — to the one-day Confederate ‘United’ States:

To get here (according to this version of the story), he takes roads not often traveled by typical travelers. On average, they are used by slaves and indentured servants who are bringing in smuggled tobacco and other goods — other people even. And while here in the south,

[h]e has certainly, and more than once, too, dreamt himself upon a dark Mission whose details he can never quite remember, feeling in the grip of Forces no one will tell him of, serving Interests invisible. He wakes more indignant than afraid. Hasn’t he been doing what he contracted to do,— nothing more? Yet, happen this is exactly what [T]hey wanted,— and his Sin is not to’ve refus’d the Work from the outset.—

(394)

Something that he saw here in the south (or something that he knew he willfully ignored) brought on this epiphany. And we’ll get to what that thing is by the end.

His dream is reality; it is the thing we have been seeing from the outset: a quest with both stated and elusive purposes, written and devised by ‘Interests invisible’ to the naked eye. Those within the back room’s back rooms have crafted these plots and contracted the men whom they believed could best enact them. However, these contracts only stipulated the stated purposes, not the elusive. The elusive, nonetheless, are right before his very eyes. So, while Dixon forces himself to believe that he can live with no regrets, thinking that he only ever used his expertise to solve a property dispute, he knows subconsciously that this is not the case. He has sinned in accepting this job; he has been to Cape Town (1.7-1.10), to Saint Helena (1.11 & 1.12), and back to Cape Town (1.17); he has known the secrets of coal well before even those ventures (1.24); and in the bit over a year that they’ve stayed here in America, the words of Benjamin Franklin (2.27 & 2.29), George Washington (2.28), the events of the Paxton brothers (2.31 & 2.34), and all else that they have seen, cannot be forgotten. So, when he tells himself that the interests he served were invisible... well, the people who enacted them may have been, but the people who were affected, most definitely, were not. Nor were the outcomes. This is a very Mason-like epiphany — one that could only have ever been seen here when Dixon, the more lighthearted and joyful of the two, was separated from him.

Dixon proceeds through all of Maryland and on into Williamsburg, Virginia where “Tobacco Plantations lie inert, all last season’s crop being well transported to Glasgow by now” (394). This is one of those unstated purposes that Dixon has been sent to America to fulfill. The same one which the ‘African Slaves’ have been brought to America for — to “keep each Dreamer safe” (394): to ensure that those who have been given the privilege to lay back and dream can do so in perfect comfort, their pipe of tobacco full, their stomach fuller, and their brain clouded with foreign liquors made from sugarcane, agave, and all other things that can be grown, harvested, and distilled outside of Europe for pennies.

However, Virginia is a place of revelation not only for Dixon, but for new Americans as a whole. They have been sent here, to America, to colonize this land, find true freedom (for themselves, at least), and, through the use of a people they deem freedom to be undeserved by, the ability to reap and sow new, affordable products that can be used at home and sent abroad. However, the supposed American Dream (the old Dream, not the one we speak of today when talking about certain Modernist literature) was rendered a joke by the Stamp Act. This act was imposed upon America in 1765 and stated “that everything printed in America be produced on stamped paper made in London” (Biebel, 128). And if there was something that America was also founded on, it was the desire to be free from taxation. The rebellion against this is something that Britain could never have predicted. Where today we typically see the Elite class working together, before the capitalist project was complete there too was internal warfare between these men. So, “The Stamp Act has re-assign’d the roles of the Comedy, and the Audience are in an Uproar” (395) even though the audience too are Elites.

Because of this, the British project of colonizing the Americas and the additional steps such as sending Mason and Dixon over to further the project are foreshadowed to be under attack. The British would not have predicted all out rebellion based on something such as this; but in reality, it was a compounding of different acts and requirements that time and time again brought the ‘Fathers’ of the American project to the level of “active Foes, capable of great Mischief” and therefore brought the “inflexible Rivals for life” who were actively colonizing and traversing this new world to be “now all but Comrades in Arms” (395) — and eventually, they would even be that.

As new acts spread, purposefully designed to get more and more out of the American people, the atmosphere of the country thus began changing. Coffee-shops and taverns were no longer mere places of gossip, not somewhere only to let loose, and not even somewhere to fuel oneself to get another day’s work done. Now, it is a place to conspire. Where something like the Session of the Burgesses2 would draft actual policy decision and communications to Britain, the gathering house (in this case, Raleigh’s Tavern3) would be used to decide on action that the people did not desire Britain to know about. The difference is that one decision is made with respect to what the government would consider the proper process while the other readily understands that the ‘proper process’ has been designed to prevent change from occurring.

Within the tavern, as he hears all of these revolutionary ideas flow, Dixon attempts to separate himself from them given he himself has come from Britain to fulfill that end of the project. Therefore, instead of seeking a severance from Britain, Dixon calls out a cheers to something that would be accepted by all but that also divests himself from this conspiracy: “To the pursuit of Happiness” (395). A man named Tom (who is Thomas Jefferson before he came to power) one day uses Dixon’s words against what Dixon wished. He asks here if he can use these words later which will be fulfilled when writing the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal & independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness” (US 1776).

Which all sounds great — a nation separating itself from an at-the-time-more-powerful and oppressive regime in hopes that this New World could build something more equitable than before. It sounds exactly like the kind of thing that we should be doing for ourselves right now: seeking a way to separate ourselves from and/or overthrow the oppressive regime to seek better life, more liberty, and the ability to attain that American Dream. But the man who will write this Declaration of Independence is Thomas Jefferson, and the irony is that he is a slave-owning, pedophilic, psychopathic bigot with enough power and wealth already, comparable to a modern-day senator, multi-millionaire or -billionaire, high-ranking military officer, or some other evil Elite. Like Jefferson is doing, seeing these modern-day analogs seeking to incite revolution holds immense levels of irony; they are the exact people who the rest of us should be seeking independence from, and yet here they are pretending as if their revolutionary action is the true path to liberty for all.

Jefferson also reveals that his father helped develop the westward running line which makes up the southern border of Virginia, further revealing the interconnection between border lines and the desires of the Elite. In the same way that the Mason-Dixon line is said to be based on legal disputes, agreements, and proper surveyorship, the Virginia line is here inferred to be based on the same. But in the end, it is men in power who make decisions according to their own personal interests. Jefferson’s father, for instance, “recorded each Day [of the line’s drawing] in a Field-book” (396) which Jefferson wished every future surveyor to read as a ‘Cautionary Tale’ about the problems with ‘Joint Ventures.’ Jefferson is warning Dixon that giving too much voice to multiple parties could lead to a contestation of the line (or contestation of any non-partisan decision), and so it would be far easier to merely let these ‘Great Men’ make the decisions since they apparently know best.

As Jefferson infers, these Joint Ventures will lead to turmoil across the lines; even though it is not outrightly stated as they spoke here, there was tension between those North and those South of the line in regard to specific laws and practices. Therefore, while the formation of the line did not bring about these specific ideologies, what it did do (or, what it would eventually do) was cordon off those who believed in them from those who did not, making it far harder to outlaw certain evils if everyone within the state (or everyone within the coming Confederacy) both believed in them and had the full legal power to maintain them given they were separated from those who did not. Men like Jefferson would ensure this foreshadowing would come to light. Therefore, his co-opting of the statement, ‘the pursuit of happiness,’ becomes even more ironic. His desire to separate from Britain made perfect sense, but his reasoning for it held no grounds once anything that would negatively impact him was at stake. Jefferson did not want to lose his slaves, nor did he want to lose any iota of his power, and so the line that would be formed would be the perfect opportunity for him to maintain these things without technically breaking any sort of law or societally ethical code.

The mood shifts a bit as the women begin to enter the bar. They are repulsed due to “their feminine abhorrence of Tobacco” (396). Immediately, the masculine energy pervades as we see it try to keep out the feminine. As seen in Knockwood’s Inn, the masculine represented the material while the feminine represented the spiritual (2.36). The masculine energy, which is attempting to remove the feminine, this time, is represented by the smoldering commodities which have been cultivated and harvested by the slaves of men like Thomas Jefferson on his tobacco plantation. The material smoke — a byproduct of consumption and gluttony — is a poison mist that drives out the spiritual facets of the world. However, while this material obsession can deplete the world of much of its spirituality, it cannot be wholly successful. In the same way, the formation of these borders which Dixon and Jefferson were discussing attempts to do something of the same, and it can only go so far. So, the women make their way into the bar.

One of these women, Urania, begs Dixon for a dance. While dancing, Urania’s fiancé, jealous and angry at this pairing, threatens Dixon and subsequently challenges him to a duel. If spirituality is to exist in this New World, then it must be claimed as an object one could own as well. Some masculine/material entity will lay claim on it. This form of duel is decided to be something not all too violent: a game of Quoits (something similar to horseshoes). And as they play “the Metal hurtling thro’ the Air […] if you listen closely enough [emits] a certain Hum” (397). Biebel adds, in regard to the ‘metallic hum,’ that “Pynchon [similarly] describes ballistic noise throughout Gravity’s Rainbow” (Biebel, 167). And if in Gravity’s Rainbow, the V-2 missile was being co-opted to become something God-like through the insertion of Imipolex-G into the 00000 Rocket, we can see that this measly and almost innocuous duel over Urania will evolve over the centuries into something far more destructive. If the material world can never fully overtake the spiritual, then one day they will merge (or attempt to merge) into a far more egregious and destructive form.

But for now, the duel ends in a tie. Both men receive “a Kiss of equal Vivacity from the fair Pretext herself” (397). Urania and all that she represents was not actually being fought after for love or anything of that nature; she was being fought after for possession: the commodification and private ownership of the spiritual. But for now, the spiritual at least has a chance. How long will that last?

With that, Dixon leaves and heads back north, looking “for some kind of sense to be made of what has otherwise been a pointless Trip” (397). However, there was a point if only he would have looked. His original intent was to find more of these so-called secrets of hegemony and why They had him mapping this border in the first place — who is running the show and for what purpose? To an extent, he did find this. He heard about the Stamp Act and how the Americans would try to fight back against it to ostensibly maintain representation for all (though actually only for the Elites); he met Thomas Jefferson and both learned about his father mapping the border between Virginia and North Carolina, plus Thomas Jefferson’s own intent to use the ‘pursuit of happiness’ line in the future; and he has been participatory in the symbolic fight to commodify the spiritual. However, to him, he has not gained any knowledge. This is all stuff he has gleaned through previous ventures.

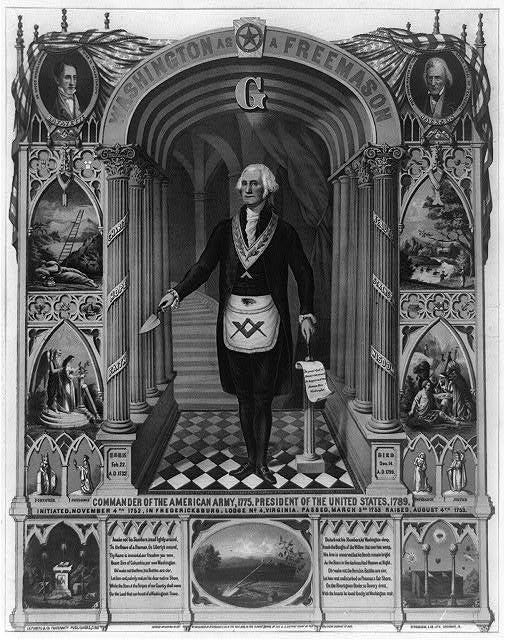

The real answer to his quest always laid before his eyes: “In all Virginia, tho’ Slaves pass’d before his Sight, he saw none. That was what had not occur’d. It was all about something else, not Calverts, Jesuits, Penns, nor Chinese” (398). No, none of these forces of power and control could ever (or would ever) tell him what the line was for. Not the Calverts who owned Maryland or the Penns who owned Pennsylvania; not the Jesuits who had a vast sweep of religious power or the Chinese whose alternative forms of thought Dixon could not comprehend; not even the unmentioned Freemasons, Hellfire Club, Royal Society, EIC, or VOC. But why did he need to seek answers in these hidden realms when the purpose laid before his very eyes. The slaves passed before him, so common that they appeared as naturally occurring cogs in a system — so common that they, like the Duck, became basically invisible. They would be background noise at best, like cars passing by on a nearby freeway. But they were the answer. These powerful men rendered slavery to be so natural that those like Dixon would ignore its presence.

As always, this is no excuse. They were before his eyes. He saw them but did not observe or think upon what was happening. Alone, Dixon has once again shown his complicity. His search for answers could be fulfilled, yet he is only willing to search within the realms comfortable, or even just interesting, to him. Instead of looking in the vast realms of conspiracy and interweaving networks that make up our world, the first place you must look is at the oppressed, the enslaved, the subjugated. Only then can you make your way outward. But until then, you will only ever see the web, and like Dixon, you will trot merrily back home, whistling a tune and thinking, ‘well, at least I tried.’

Up Next: Part 2, Chapter 40

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.

The House of the Burgesses was the meeting location for the governing body of Virginia from 1619 through 1776.

Raleigh’s Tavern was a location where other, more conspiratorial, decisions were made by men in power — decisions that these men would want to keep more ‘on the down-low’ compared to speaking on them in a political office.

Great writeup as always. I may be misreading you, but I believe Jefferson Davis was president of the Confederacy and not Thomas Jefferson. Both big fans of slavery though!