Mason & Dixon - Part 2 - Chapter 26: Arrival Themes

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 2 - Chapter 26: Timothy Tox, Arrival in America, Advertisements and Trade, Peddling Religion, Musical Allegories

Mason and Dixon’s arrival in America is epigraphed by a passage from Timothy Tox’s, The Line. Tox, a poet earlier mentioned by J. Wade LeSpark (1.22, pg. 217), focused on sentimental poetry regarding American idealism and the ‘ever attainable’ American Dream.1 The passage begins by recalling the eighty years that the property dispute — which led to Mason and Dixon arriving in America — was laid up in court, again reminding us of the ‘coincidence’ of that dispute being so perfectly timed between the two Transits where the astronomers would be free to map such a line. The passage reveals much of the corruption within the line’s drawing, from one state having more legal claim to territory while those on the other side know more powerful people and could likely get around these legalities. Tox infers the presence of lawyers who will line their pockets with legal fees along with the tendency for mankind to trace borders over borderless land. All a massive criticism on humankind’s draw toward corruption, but not one specific to America. And certainly not one which predicted any alternative use of the Line outside of the property dispute. Part 2, America, is therefore introduced with the knowledge of conspiracy — if you could even call the knowledge of governmental corruption ‘conspiracy’ — without the mere mention of anything beyond what everyone already knows. Of course, we, and they, are aware of the corrupt politics of border surveying, of lawyers trying to make a bit extra, of mankind’s desire to possess more land than our neighbor. But what else could there be? To Tox, to many ‘Americans’ in 1763, and to many Americans even now, nothing — why would there be anything different than what we already believed was present in civilized Europe?

But oh, how wrong they are.

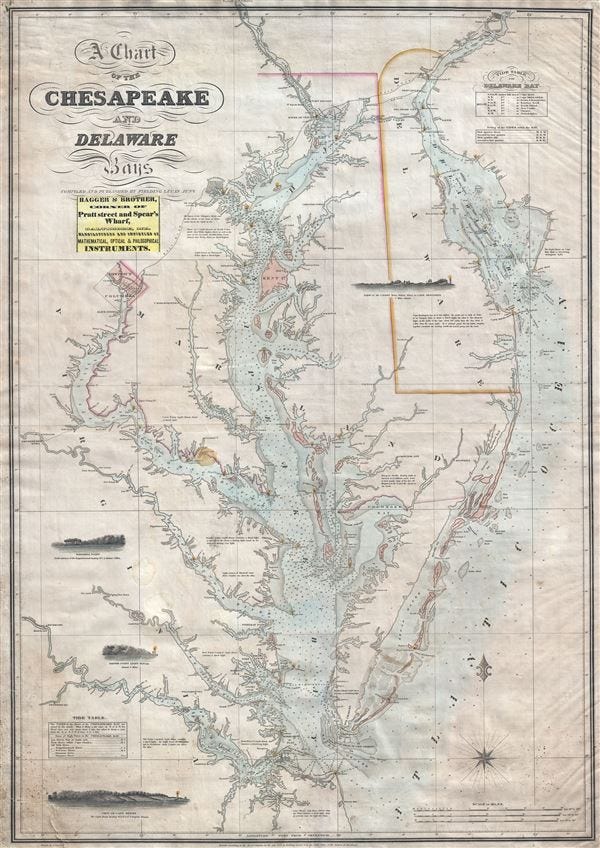

Mason and Dixon’s arrival first takes them up the coast of Delaware and onward down a river to Pennsylvania where eventually “they single up all lines” (258)2 — meaning both the removal of ropes upon the ship for docking, but also the removal of coming historical possibilities. Mason and Dixon’s arrival in America was one of these historical turning points — one which, now that we’ve arrived here, has cut off a series of near endless possibilities. In this case, the ‘singled up line’ is a metaphorical wire taking history from England to a specific American coast “with a long history of white expansion/colonialism and ensuing violence” (Biebel, 119).3 This, unsurprisingly, is the path that has been chosen: a path of the West’s continued expansion outward, severing the other ‘lines’ that could have led elsewhere — could have led to something at least somewhat less condemnable.

Debarking, Mason and Dixon stand upon American soil for the first time, “feeling like Supercargo” (259) — ‘supercargo’ defined as the representatives upon a ship who have the task of overseeing the sale of the ship’s actual cargo. In this case, the ship has no real cargo which Mason and Dixon are to be responsible for. But the vast array of cargo being unloaded and loaded onto and off of various ships surrounding them, ranging from “casks of nails and jellied eels” to “shreds of spices and teas and coffee-berries” to “Pills Balsamic and Universal, ground and scatter’d” (259), is what they see themselves the representatives of. Or in other words, respectively, the expansion of construction, of foreign foodstuffs, of the spice and caffeine trade, of pharmaceuticals, and so many other ‘goods’ mentioned from slaves to labor to liquor to fruit. America and that which America represents will be the hub for this trade, and Mason and Dixon get a glimpse of their part to play in this. Because, if they were to achieve their goal here, this form of commerce and distribution of cargo would be ever altered for the better (in the eyes of the salesman, that is).

And speaking of salesmen, how could something be effectively traded en masse without advertisement? On their way to their temporary housing, that is exactly what they see. Advertisers crying out lies meant to entice others to buy products they probably do not need. Love potions — the exact same ones used by Don Juan and Casanova! apparently — are somehow being sold right here in America. Addictions are fueled via the sale of the most secretive vessel: a flask, themselves being advertised to assist in the other major addiction of the time — gambling. Foods such as pizza being tossed up into the air by a beautiful foreign woman are described with sexual innuendo: “See her handle it […] with all the female exuberance of her Race” (260). Even gambling itself is being advertised through the installation of a fear of sameness; the crier asks them, if you don’t hit it big here, then what’s next? Hopelessly chasing more women? Going to a tavern to drink and hopefully win a couple coins gambling with simpletons? Getting back on the boat, singling up all lines, and setting out to some other hoped-for greatness? Even religion is being peddled by a man named Reverend MacClenaghan who ‘preaches’ in the televangelist style, drawing everyone from countryfolk to Quakers to buy into his act.

If it can be bought and sold, the new order will find a better way to sell it. Because America will be the defining state to ‘perfect’ capitalism — will it not?

At the LeSpark’s home, Cherrycoke elaborates on the last salesman of the previous passage, referring to his act as the peddling of something he calls ‘The New Religion’ — taking the silent and personal worship of a holy deity and twisting it into something ostentatious and even profitable. Ethelmer calls out Cherrycoke, seeing that while our Reverend may be condemning this ostentatious form of evangelizing, he also refuses to admit fault in the less ostentatious but still predatory forms of conversion or general worship. Cherrycoke, in an attempt to save some face, admits that other peddlers were out there attempting to use religion for the purposes of commerce, but states that they were eventually rooted out. Deflecting further, he then calls out those like Whitefield, someone who preached so extravagantly and bawdily that he had “People standing up on Ladders at the Church Windows” (261) in the style of a modern-day mega church.

DePugh4 comments on how because of such blasphemous treatment of Christianity, there should be “No wonder there was a Revolution” (261).5 Euphrenia6 responds, “Hmph. Some Revolution” (261). And she was right (we’ll get to why). Ethelmer responds, chastising her for not seeing the importance of such a revolution, citing Plato’s Republic itself, referencing the quote:

And they should dread to hear anyone say:

People care most for the song

That is newest from the singer’s lipsSomeone might praise such a saying, thinking that the poet meant not new songs but new ways of singing. Such a thing shouldn’t be praised and the poet shouldn’t be taken to have meant it, for the guardians must beware of changing to a new form of music, since it threatens the whole system. As Damon says, and I am convinced, the musical modes are never changed without change in the most important of a city’s laws.

(Plato, Republic, Chapter IV)7

Finally, Cherrycoke comes back, telling Ethelmer he is misinterpreting the quote, stating that Plato had an issue not with those who were not changing music, but who were merely “mixing up one with another, or abandoning [Forms of Song] altogether” (262) — exactly what is stated in the actual quote above. Which goes to show that it is important to recall the full quote rather than just what one wants to remember about the quote.

To break all that down so far, DePugh initially believes that the American Revolution both stemmed from and was justified because of the blasphemous treatment of Christianity, seeing how it was being treated as an English commodity. This itself, the perversion of religion, can be taken outward to just about every commodified ‘thing’: food, art, music, and all products of all labor. And that is what many of the founding fathers may have believed — thinking, or stating that they thought, that a freedom of religion and freedom from an oppressive government would allow the chaos of the emerging imperialist powers to be subdued in our new, ‘innocent,’ nation. Euphrenia’s response is probably similar to most readers’: ‘well so much for that idea.’ Because while the Revolution was said to be for this purpose, the insanity that was trying to be suppressed was in reality exacerbated. Freedom of religious expression was traded for the genocide of traditional indigenous beliefs and indigenous people as a whole; freedom from taxation from a foreign body was traded for the ability to expand profitable markets elsewhere, consequently raising new ethical qualms far more egregious than taxing a foreign nation for exports; freedom from a foreign monarchy was traded for the rise of an invisible ruling class purportedly ‘of the People, for the People,’ when in reality it would take the oppressiveness of the overthrown government and make it seem like a class utopia. Ethelmer’s response, subverting Euphrenia’s harrumphing, states that the ‘music’ — the zeitgeist — of the nation had changed, and thus the nation itself must be changing. I mean, even Plato stated this would occur. And if we cannot trust our great first philosopher, then who can we trust? But of course, Plato’s actual quote does not merely state that a change in musical style signifies real societal change, but that art as a whole can be a threat to power structures; it is not that a change in A leads to a change in B, but that A itself can foment rebellion. It is not ‘change’ but ‘intention’ — and mass absorption of that intent. Cherrycoke’s final comment infers that yes, this was not a radical change in ‘music,’ but merely an abandoning of one style for another that truly had no difference from the original — though, it could appear different enough to make it seem like times were a-changing while they just replayed the same track over and over again.8

Euphrenia then backs this up, stating that the change in music in reality is just “hearing but a careful attending to the same Forms, the same Interests, as of old” (262). In other words, the key or the tempo or the time-signature might be changing, but the intention is remaining the same. This is merely faux innovation in musical style so to just use it as a pretense to maintain the same system we’re already under. A key change may just signify the next step in an ever-recurring cycle, but all it is is a key change and nothing more.

Ethelmer, kind of forgetting the whole root of the conversation, attempts to impress Brae with some music. But even with his inability to stop thinking about wooing her for just a second, he plays a song for Brae and does add a good point. The music that he plays is, “sentimentally speaking, a ‘Sandwich,’ with the third eight ‘Bars’ as the Filling” (262). A sandwich is “a food that allows for a measure of invention/freedom, provided it falls within a clear, established structure” (Biebel, 121) — a sandwich is a sandwich is a sandwich. So much can be radically altered within it, but this change without intent is meaningless unless one’s goal were merely to try a different sandwich or listen to a new type of music or — the point of this all — to live under a new governing style that may have some alterations, but not in any radical way (a whole new style of music versus the same song in a different key).

And back to Euphrenia: because sure, a basic change in style will not radically alter our worldly trajectory toward a more equitable future, but this does not mean that all forms of music — or any type of art for that matter — are equal in what they can achieve. Ethelmer’s song was a bawdy drinking song, something that follows the same formula time and time again with a change in lyrics that only are there to either increase the positive mood or just to make the singers and listeners laugh — something akin to pop music or a beach read.9 Euphrenia’s music is more complex allowing for more of that so-called sandwich filling to not necessarily change the object from a sandwich to something else, but to alter our perception of what a sandwich could be. Her music allows for this expression just as something like jazz allowed for radical societal shifts10 or how literature like that of Thomas Pynchon gave us insight into wholly new worldviews and realities we may have never seen otherwise.

Euphrenia’s current argument continues in a way that initially seems to counter her original argument. Her ideal is a “Hero instead of proceeding down the road having one adventure after another, with no end in view, comes rather through some Catastrophe and back to where she set out from” (263). A bit regressive, according to Uncle Ives. What possible revolutionary action could be gained from a return to the way things were? Typically, not much. But if the coming ‘progress’ was rooted in a system which could only survive on the abuse and exploitation of a whole population, then maybe a tradition rooted in something else is not so bad. The ideological perspective that solely equates tradition with conservatism is the same that equates progress with ‘progressivism.’ Not all ‘progress’ is progress for the People, it is often progress for the sake of advancement at any cost. Similarly, tradition is not always reversion to conservative ideals; it can often be the desire to recenter the focus on community or other like ideologies. In this way, words have been divided, losing their meaning only to inflame that which may be the better definition or desired use of. The division of words has therefore divided a people. Thus, Ives’ response: “Doesn’t sound too revolutionary to me[.] Sounds like a good sermon aim’d at keeping the Country-People in their place” (263). As he himself is rooted in the desire for the more maleficent version of traditionalism, he will use the division of words to pit sides against each other. Of course, he wants conservative tradition to maintain its grip on the ‘New World,’ so his attempted subversion of the more altruistic facets of ‘tradition’ is not to actually attempt to bring on the altruistic facets of progress, but to put the two sides against each other, maintaining the negative aspect of each. Because, if the negative proponents of progress (the neoliberals) continue to fight against the negative proponents of traditionalism (the neoconservatives), then that is all either of the ‘two sides’ will ever know. The feud will never allow for nuance between the sides or beyond the sides. Humanitarian traditionalism and progress that centers the community will never take flight if the more horrendous sides of the two words are all that anyone ever knows.

Cherrycoke poses the final musical allegory, seeing the danger in views like Ethelmer’s. While Ethelmer tries to center his love of these communal drinking songs in something more worldly and revolutionary than everyone else is making them out to be, Cherrycoke sees past his virtue-signaling. Ethelmer’s point — that in “the Negroe Musick […] there sings your Revolution” (264) — is accurate. Cherrycoke knows that Ethelmer couldn’t care less about any so-called Revolution or any societal change that could free the slaves from their bondage. Ethelmer simply knows, through listening to the story with her, that Tenebræ has a deep morality, and would thus respond well to his advocation for (or at least an awareness of) the power that is behind a possible Black revolution. And she does respond well, because although she is one of our most compassionate and naturally intelligent characters, she is only a teenager. While Ethelmer is also just a teen, the difference is that Ethelmer is placing the spiritual songs of the slaves at the same level as the white man’s drunken chants while she is merely enchanted by his affection. So, it is not even just virtue signaling in the attempt to attract a woman of a much higher caliber than he is in the same way that many college boys will similarly do today, but it is also a full reduction of the former style of music and the possibility of emancipation as a whole. The only two possibilities that could occur in the conflation of these styles of music is either the elevation of the drinking song (i.e. art in the sense of pure entertainment), or the reduction of the Black Spiritual (i.e. revolutionary art) to the point that it is an artform that is not taken seriously. Either way, his virtue signaling holds dire and dangerous possibilities if it were a form of thought that could spread, just as Cherrycoke believes it will.

And unfortunately, Cherrycoke is likely right; because as we see, Brae, still falling for Ethelmer’s shtick, gives him “a length of scarlet Muslin, which the game Ethelmer has ‘round his head in a Trice,” (265) effectively dressing him “like a stereotypical fortune teller” (Biebel, 122). Whether he knows it or not, — whether he intends it or not — what he is foretelling is exactly how America will evolve.

Well, Mason and Dixon are here, and within moments they have been introduced by a severing of historical possibilities, the realization of coming global markets, the use of psychological tactics (advertising) to enable these markets, and a series of allegories that are just as ominous if not worse. Not great tidings on our first venture into America.

Up Next: Part 2, Chapter 27

In 1.22, Tox was mentioned in the conversation about the hypnotist Mesmer where DePugh desired to start a similar business in America. J. Wade dismissed the claim of small-town America not being a place this could be done by using a line from Timothy Tox’s Pennsylvaniad and its tendency toward a romanticized westward expansion.

This quote is also one that begins Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day, — “Now single up all lines!” (Against the Day, 1.1, pg. 3) — his next book both publication-wise and chronologically in history. It heavily explores this concept of historical turning points (and quite a bit more, obviously, given its immense size).

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.

Brother of Ethelmer and son of Ives LeSpark. First seen mentioning Vectors of Desire (1.10) and last seen discussing his brainwashing by Mesmer and desire to open up a similar practice (1.22).

Remember, while Mason and Dixon’s journey in America took place pre-Revolutionary War (1763-1768), the frame story where Reverend Wicks Cherrycoke recounts their adventure takes place in 1786, about a decade after the war.

Sister of both Elizabeth LeSpark and Reverend Wicks Cherrycoke. She arrived at the house shortly after DePugh did, around the point when Cherrycoke was elaborating on Mason and Dixon leaving Cape Town and also when Brae was expounding on her love for discovery (1.10). Euphrenia, in that chapter, was the symbol for the freer, more untethered woman compared to Elizabeth LeSpark, setting an interesting example and counterpoint for Brae. She also was shown to be partially dependent on commodification and global trade both with her possession of foreign musical instruments (1.10) and with her love for Saint Helena in the ostensibly ‘good’ days (1.11). This dependence, though, was not a condemnation; she simply liked nice things and tried to find the least exploitative ways to get them.

Plato. “Republic.” Plato: Complete Works, edited by John. M. Cooper and D. S. Hutchinson. Translated by G.M.A. Grube, rev. C.D.C. Reeve. Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 1997, pg. 1056.

And all of this should remind you heavily of the Henry Vane analogy which Christopher Maire made to Dixon shortly before his departure to America (1.22).

Don’t get on me for comparing fun drinking songs to pop and shit lit. I know drinking songs are way better, but you get my point thematically.

An important discussion about jazz’s ability to radically alter society can be read in the Roseland Ballroom chapter of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (Gravity’s Rainbow, 1.10).

'Euphrenia’s current argument continues in a way that initially seems to counter her original argument. Her ideal is a “Hero instead of proceeding down the road having one adventure after another, with no end in view, comes rather through some Catastrophe and back to where she set out from” (263). A bit regressive, according to Uncle Ives. What possible revolutionary action could be gained from a return to the way things were?'

For me the first thought I had and connection lay in the Odyssey. Which is a story of back to back adventures going towards a coming home story. The longing of a man hoping to find things as they were as he sidetracked and lost among large forces of god's throwing things into the mix. Eventually accepting that time has moved on, and that his journey while great was not what he wanted (coming home quickly).

Pg 264, the "South Philadelphia balled-singers..." I want to believe that's a nod to the Philly Sound soul music. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philadelphia_soul