Gravity's Rainbow - Part 1 - Chapter 8: Beyond Response

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 1 - Chapter 8: Pointsman and Spectro

With Roger and Jessica on their way home, we follow Pointsman into St. Veronica’s — the lights are dim, mutterings of pain and confusion lay humming in the halls, scavengers come out of the woodwork to feast on old stains. Through the obscured scene we see Kevin Spectro emerge, one of the keepers of The Book, watched by Pointsman himself, as he injects some substance into his Foxes: the name he gives his human patients. Pointsman, tired of his dogs, finding them much too hard to capture let alone make sense of on any human scale, envies him, wishing instead he could conduct his trials on something that he could better comprehend.

Through their discussion of human patients, the topic of Tyrone Slothrop once again pops up — it seems that everywhere in this zone he is a topic of conversation, a man we barely have seen, yet everyone has an interest in. The terms “precognition” and “psychokinesis” parallel with him, as do the fact that he was a one time subject of a man named Laszlo Jamf. So far we know that Slothrop and his family line are a metaphor for America and America’s mythology: those who lived within it trying to fight another day as well as those who have succumbed to the greed inherent in its creation and existence. We have seen intelligence agencies secretly observing their patterns Slothrop/America/The World creates in hopes of understanding the desires and inner workings. We have seen groups discussing its/his surveillance and what this information may lead to or mean. And now we see two men, higher ups in the realms of intelligence (though, of course, not the highest ups), desiring to use him for future experiments revolving around conditioning — though it is perhaps possible that he may have already been conditioned for something else. Not that that matters, his past conditioning can of course be studied and used in the modern world

There are opposites, every sort of opposite: “pleasure [and] pain, light [and] dark, dominance [and] submission” (48). Could these forms of conditioning create the idea that one has control over ones life yet may actually be the controlled? The person being unable to live on one end of the spectrum creates some sort of cancelling out by believing they exist on the other. Recall our séance, the invisible hand holding sway, telling us that everything is naturally balanced, yet when we look, when we truly seek those pieces of evidence that our society does, in fact, balance itself out, how come we never find a certainty? So comes the “response before stimulus,” (49) the belief before proof, us being told that something is at it is, never being shown; accepting it as fact — the ultraparadoxical, the extrasensory.

Though, as Pointsman states, “the act merely of bringing the dog into the laboratory […] would be enough to send him over, send him transmarginal” (49). The dog is to the laboratory as Slothrop is to the War, and Slothrop being a partial stand in for America, we can assume we will be observing how the War and its near infinite branches are used to condition the American or the average person. What toll will they have? What will it make us do? What levels of oppression will it make us okay with? And what does it mean that the mere act of sending us into the War will send us transmarginal1? Will the horrors grow so great, that our response, in order to preserve our last bit of sanity, shut down entirely?

Pointsman again realizes that the key to his trials, to learning and documenting the truths about control, stimuli, response, is to put the dogs aside and begin the experiments on people, “poor human palimpsests shivering under their government blankets, drugged, drowning in tears and snot of grief” (50). They are these palimpsests that he needs — subjects whose personalities and beliefs have been formed atop them by those above them, who have been rewritten and transfigured so many times that their own identity is not their own. And in one of Pynchon’s many shifts to second-person, he calls on you to be their savior — you see how the state of these subjects — children, exhausted, crying, selfless, innocent — being used for the furtherance of the State cannot be allowed to go on. You must be “the Traveler’s Aid” (51).

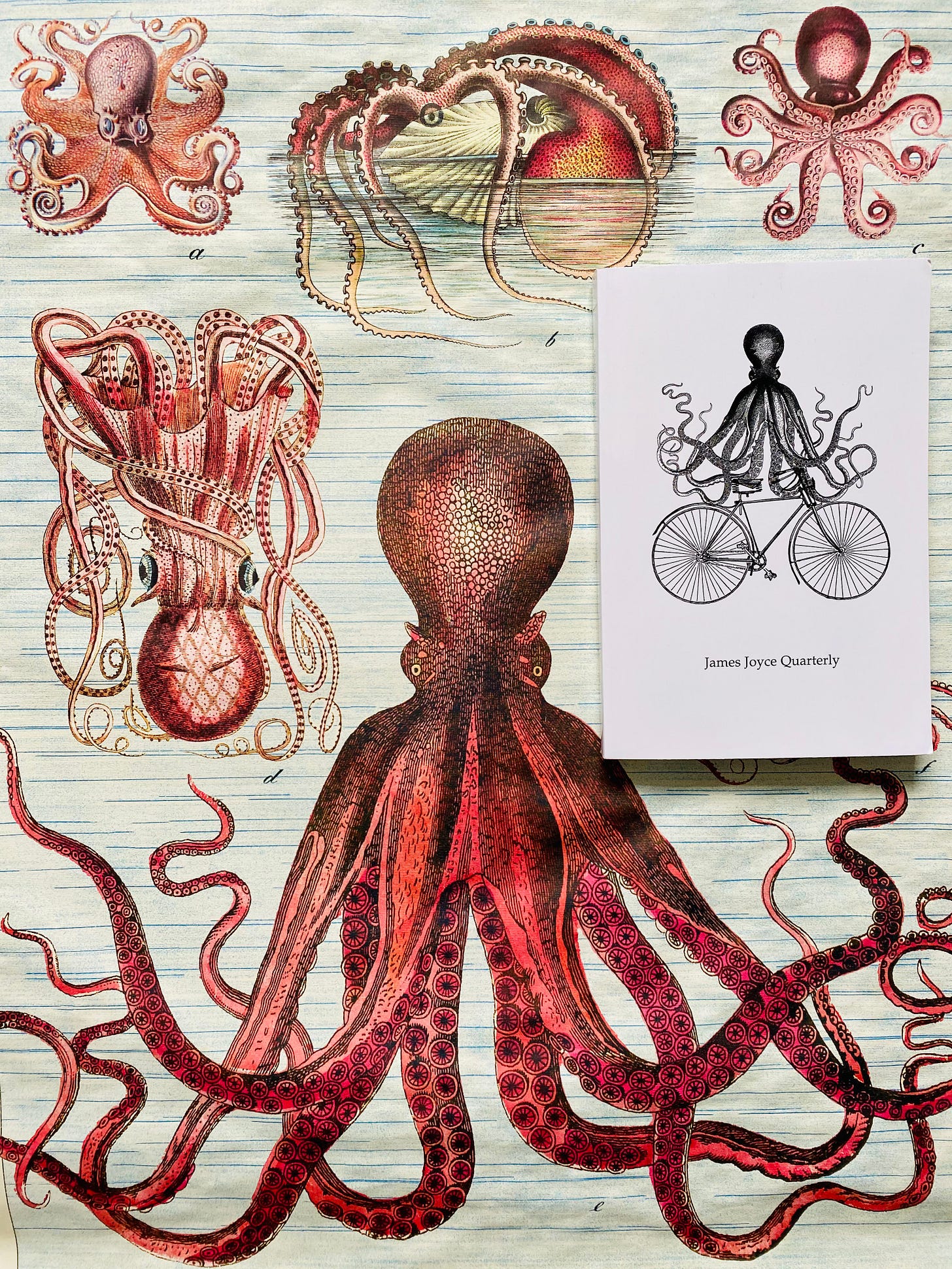

In the meantime, whether he gets his “fox” or not, Pointsman has a new subject to condition: a gigantic octopus — “gray, slimy, never still” (51) — known as Grigori, another Russian name, something he can manipulate and train to further his own goals, in getting one step further to our hopeful hero.

Hi again all! I will be going on vacation from tomorrow until Sunday, and then later next week my summer break will be over and I’ll be sadly heading back to work (though, I am kind of excited because I am trying to get The Crying of Lot 49 approved for my Honors Seniors). So it is possible that I may have to delay next week’s post by a week, though I still do think I should be able to maintain the schedule. But I’m letting you know ahead of time just in case.

Up Next: Part 1 — Chapter 9

A response to stimuli that far exceeds one’s capacity.

Really interesting...I hadn't seen that parabolic graph of behaviorism before; of course it makes utter sense that it would be a parabola and so mirror the Rocket's path.

Continuing to turn pavolovianism over in my mind since last week; for me, it is revealing to contrast Pynchon's emphasis here with the prevailing civilian theories of mind that were dominant in his moment, namely, psychoanalysis. Pynchon resists and mocks psychoanalysis in the text--I argued in my thesis that GR is parallel with Deleuze and Guattari's resistance to freudianism, that it was anti-oedipal. Pavlov was nothing if not an empiricist, only venturing into the realm of psychology after years of studying the body's physiological reactions. We now know that the two (mind and body) are profoundly interrelated: the conditions of the body do much more to determine the conditions of the psyche than any symbolic construct erected in a child's youth. It is the parasympathetic or autonomic nervous system that was manipulated to create baby Tyrone's small erections. So while someone like Philip Roth was out creating self-indulgent (onanistic in the literal sense) fables based on symbolic Freudian constructs, Pynchon was out there calling out the secret/occulted technologies of the mind that were being developed while the counterculture was distracted with psychoanalysis and acid.

Pynchon was obviously writing against (satirizing, lampooning) the military-industrial complex's experiments with mind control/behavior change that would only become common knowledge much later, and would never be a topic of conversation in polite company, and yet has now been thoroughly documented. Throughout that whole time period, from WWI on, but reaching a real climax both in world war II and then an even bigger climax in the MK-Ultra programs of Pynchon's day (which are still ongoing), countless clandestine organizations both domestically and globally were conducting research into mind/behavior control by this kind of pavlovian conditioning (stimulus, response), using the science of cause and effect to increase susceptibility to hypnotism, suggestibility, and so on. Behavior control was demonstrated to be effective, and more importantly, cheap and straightforward to study: pay Michael Aquino to traumatize some children, see what happens. At a minimum with these blunt, abusive instruments, they became adept at a minimum of creating disassociated personalities (think Sirhan Sirhan), which were obviously useful in the field of clandestine control in which they operated. I think Pynchon saw this stuff clearly, and saw that eventually the military style of pavlovian control would eventually and inevitably colonize the civilian psychological space (as it has, with ABA, CBT, etc.) Or at least that it had the potential to do so -- he need not make a prediction to make a profound point here.

Pavlov/Pointsman/Jamf is our main rubric that the author gives us to try to understand the mystery named Tyrone Slothrop--why he is so important to so many, why he is the sole subject of ornate systems of surveillance and control. I guess it could be said that in the third part of the novel, when he's running away from something, it is his Conditioning that he is running away from...

How do you read or understand Spectro's refusal (or at least reluctance) to give Pointsman his foxes? Is there some kind of moral line for Kevin that he's shying away from, some ethical division between his work at the hospital and Pointsman's at the White Visitation? If so, it might seem arbitrary and hypocritical (perhaps that's what Pynchon wants us to think). Or it's budgetary and bureaucratic perhaps? Pointsman obviously believes it's personal, it's a personal slight.