Gravity's Rainbow - Part 1 - Chapter 7: The Old and the New

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 1 - Chapter 7: Dognapping with Pointsman

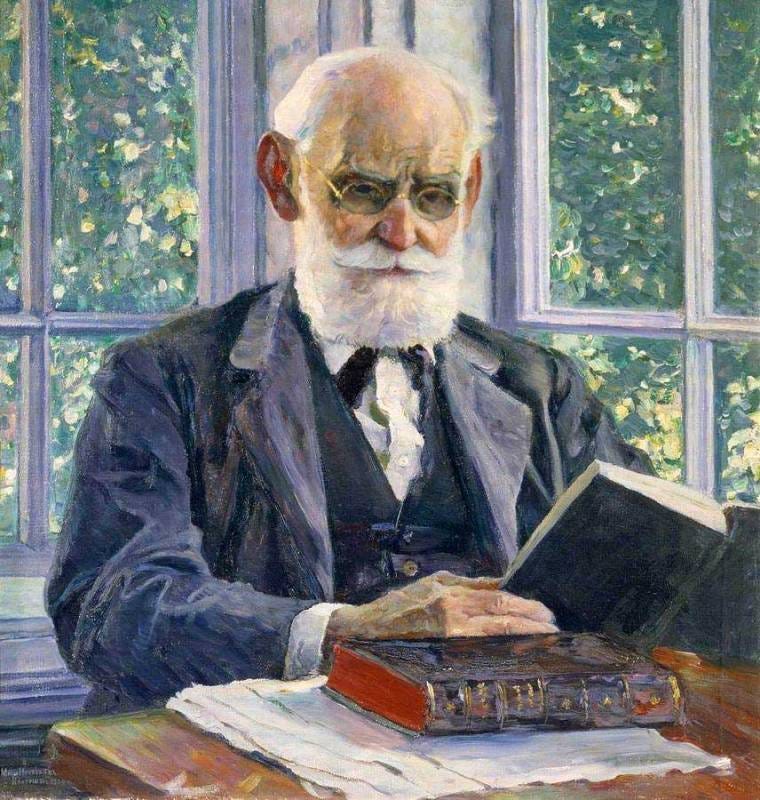

Today, Roger and Jessica are on their way to make a rendezvous with one Pointsman, a Pavlovian who performs certain experiments on dogs which he captures in war torn London — dogs who Pointsman names “Vladimir (or Ilya, Sergei, Nikolai, depending on the doctor’s whim)” (42). Despite it being World War II, the West was already finding its bearings in the anti-Russian/anti-Leftist sentiment1, and Pointsman, like Slothrop in a later chapter, steps directly into a toilet but, unlike Slothrop cannot see the shit which his people have and will perpetrate onto one another. He is instead stumbling about, crippled by the idea of having to come to terms with his bigotry or Fascist tendencies (or, at least, unaware of what the vessel may be trying to tell him). To some extent, he is incapable or unwilling to change his outlook. No matter what history may lie ahead or what evil may lie at his root, his plan must move forward. His plan though, as of now, remains unclear — though as a Pavlovian, it is sure that his interests lie within within the realms of control (set out in explicit terms in Chapter 6) and conditioning (which is coming).

Roger and Jessica find him in this awkward state in the middle of a bombed out building — one destroyed by a V2 rocket that “took down four dwellings the other day, four exactly, neat as surgery,” (43) as if that was all it was intended to do — not to enact some specific plan, but just to destroy. Jessica is the only one to react to the horrible situation on an expected emotional level: she sees the dog that Pointsman is after and imagines it “waiting in the night and rain for its owner, for its room to reassemble round it” (43) because to her the refuse of this war is as sad a thing as the death that stems from it. War may be all she has ever known, it may be the very fiber of her being, but that does not mean she cannot fathom, desire, or fight for change. Think of systems we live within — they are all we have ever known as well, but do we not hold back tears as she does as we look upon their ruin?

Roger, yet to react to much being the desensitized nihilist that he is (though remember, this is not a condemnation of him as it is of the society which has made him as such) is simply ready and willing to help Pointsman catch his dog, despite him likely seeing some of the more nefarious reasons for this act: the dogs being a stand in for those war time victims now being sought and exploited to better perfect our techniques of control and conditioning. As they are continuing the chase, the dog has a thought while picturing the “light” from the day before: “Light from the rear signals death / men with nets about to leap can be avoided” (45) — the new war versus the old, both terrifying, but at least you have a chance against one. And, with that, the dog does manage to escape, it had that chance, and did so in quite a comic fashion too, leaving the building to crumble nearly on top of its pursuers. Pointsman, fed up with this type of chase, lets his mind wander off onto other forms of prey. How else, what else, or who else, could he capture? Roger holds his silence.

They retreat back to the Hospital of St. Veronica, a structure built on the subconscious philosophy of the labyrinth: where humanity lost its interest in building upward, reaching toward or pondering the search and existence of God, any deity, or even anything grander than us, but has now decided to build the maze, a place designed on the idea of fright and escape, where we could live among (but still hide from our sight) the “industrial smoke, street excrement, windowless warrens” (46). Here, Pointsman needs to speak with one Dr. Kevin Spectro, “casual Pavlovian” and “one of the original seven owners of The Book” (47). Though, whatever that may mean will have to wait, for not even Roger and Jessica know. They instead are bound for home, hoping for a bit of peace.

Things are moving along smoothly on my end! Currently around page 500 of the reread (over halfway into Part 3, not that I’m writing about every chapter as I go, but you know, I feel like it helps to remember what happens later as I write about earlier chapters) and God damn this book is perfect.

Next week should cover the whole of Chapter 8 since it is a relatively short one, but I’ll let you know if things change because I recall it being very dense.

Up Next: Part 1 — Chapter 8

Read Jed’s comment below. The dogs are named the same as Pavlov’s. So while the tendency toward anti-Communist sentiment may be pertinent here, it is more likely (though both could be true) that it is actually Pointsman’s love for tradition and love for Pavlov that lent these names their importance. Which in a way humanizes Pointsman and shows how the systems which formed his adoration of and belief in pure science may make their way into the human mind through faux-emotional connections.

I do have something else to say about the Pavlovian aspect of the novel, was trying to decide whether to post about this here, or later, but here we are. In college, I focused on other aspects of the book, but then I had an autistic son and was struck by the capacity that this book has to be the most articulate enunciation of so many different things that become relevant at different times in life. I haven't really tried to write the following down; maybe this feels like an unthreatening context for me to do so. My son was diagnosed at age 2.5. We were living in Brooklyn; I called the diagnosing psychiatrist (sent as part of our early intervention evaluation), and he patiently explained that my son needed 40 hours per week of ABA therapy. For the past 2.5 years, I had been struggling to work exactly 40 hours a week on no sleep and with no family support -- every minute of childcare that I didn't perform had to be bought (My wife was similarly strung-out, of course, but she worked in Big Law and had to work many many more hours per week, and we had to prioritize that). So my baby boy got his own first full-time job, being conditioned (though we never really got above 20 hours/week), and I was (and am) completely sure that this was, if not what he needed, then at least the very best we could do for him. Our choices for intervention in Brooklyn--which, when it comes down to it, is a very conservative city in many ways--were: terrible ABA services covered in-network by insurance (the online reviews were terrifying reading), and the best-in-the-world ABA services. We read books about people doing other kinds of interventions (like Barry Prizant's book), but none of those services seemed to be available; there was a once-a-week hour long playgroup in New Jersey, whereas ABA service providers were available to spend hours a day working with him. So we paid, out of pocket, for the very elite ABA, performed directly BCBAs rather than BTs, and it was good. It gave us a start. In those days, he was constantly screaming. Being conscious seemed to be immensely uncomfortable for him; the worst was when he was waking up from sleep, which seemed like a physically painful process. At 2.5 he had no reference point in the world, nothing to hold on to: he didn't know how to play. Whatever that thing is that very young kids do to explore the world: he didn't know how to do it. ABA showed him how to learn something: by repetition and determined practice, by pushing through the pain. If being alive was painful, at a minimum uncomfortable for him, then he'd have to learn how to learn despite the discomfort.

Conceptually speaking, ABA is not far evolved from vulgar Pavlovianism. You identify your target behaviors, and then run trials, rewarding successful attempts and, in our case, ignoring rather than punishing undesirable outcomes, and this latter part is how I made myself comfortable with the practice. If it was traumatizing, it would only be the trauma of trying to do something difficult, and failing; not of being punished from an outside source. Nonetheless, today's behaviorism generally is fundamentally Pavlovian: ABC, Antecedent, Behavior, Consequence. Pynchon shows us how to wonder how information can be encoded into the antecedent in ways that are legible in the behavior. For us, ABA was more about training the parents than the kid; we were forced to tolerate & endure seemingly endless meltdowns; autistic advocates would surely say I'm centering my own pain when he was the one doing the crying and therefore obviously the one in distress, and they'd have a good point, but the fact is that ABA didn't end up doing much, really changing much. The thing with keeping track of data is that you can see the limitations of the data: he'd have good days where he met his goals, and many bad days when he didn't, but both parents and therapist agreed that he knew how to do the thing, was capable of doing the thing, but just didn't because he was tired, or maybe didn't want to. ABA didn't increase the number of good days and decrease the number of bad days. We stopped it after we moved to California -- we moved around age 3.5 and stopped by age 4. He's 7.5 now. I think in the end the only thing that "worked" was time passing, him growing on his own.

But it struck me how....wise?...it was of Pynchon to linguistically metabolize the 20th century love affair with behavioralism that was still so active at the time he was writing, in the MK Ultra programs that were brainwashing and derailing the counterculture and defanging the antiwar movement...these technologies of behavioral modification really were the subject of much obsessive investigation on behalf of the anticommunists, and it there can be no question that the victims of these programs were like Slothrop used, traumatized and discarded, and greatly suffered as a result. I don't think that's what happened in our family, to our son; you have to be capable of nuance. But as with Slothrop, part of that nuance is that we had no other options, no other type of support to deal with a disability we never could have planned on. ABA was and still is the only evidence-based therapy for autism (besides speech and OT, which are sort of "for" other things), the only one that would be covered by insurance, and so it is still over-determined by history that our son would participate in ABA in the same way that it was overdetermined that Baby Tyrone was surrendered to the inquisitive care of Dr. Jamf. ...

Pointsman's names for his dogs are the same as Pavlov's for his lab dogs, or at least recall Pavlov's dogs (Pavlov of course having been Russian/Soviet), so I'd see it more as his bookish devotion to his intellectual tradition, but I support the project of finding hints of the pivot from anti-fascist to anti-communist tendencies.

Weisenberger identifies The Book as volume 2 of Pavlov's Lectures on Conditioned Reflexes, which includes the letter to Prof. Janet that is directly quoted later in this section.