Mason & Dixon - Part 1 - Chapter 6: The Microcosmos

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 1 - Chapter 6: Tenebræ's Confusion, Lomax Arrives, the Brilliant, Captain Grant, the Military Band, the Equator, the Higgs-Boson, a Microcosm

The previous chapter’s letter exchange is now being discussed in the home of the LeSparks. Despite the fact that they were both threatened with legal prosecution if they disobeyed, Mason and Dixon cared a bit more about the preservation of their lives than the act of legal repercussions. So, while they agreed to continue with the plan to map the Transit of Venus, they did at least try to change the location at which they would observe it. And yet, in return, they are continually threatened: “No matter that the Astronomers were right and the R.S. wrong,— they had to comply” (47). As discussed previously, the profit that the Elite must procure far outweighs the safety and well-being of anyone below Them, at least in Their eyes. Brae (Tenebræ), being the bit of hope we have for America’s future,1 does not see the rationale in this. How could an entity be so cruel so as to risk the lives of our beloved protagonists just to procure a bit of data? Is the gain worth the loss of life? Do they simply see those below them as irrelevant and thus are willing to dispose of any and all souls? Does the data, in reality, not even matter all that much? thus leading to the conclusion that Their appearance of power or Their desire to control is even more important than what They can gain?

The fact is that often yes, the appearance of power and control is often more important. For, “when next our Astronomers put to sea,” (47) the Royal Society did send them somewhere else, though now supposedly of Their own volition as opposed to the request of their underlings. Even if that was the plan all along, a body as powerful as the Elite must appear to hold utter control. As in the modern world, when an employer may easily be able to give someone a day off or even let them go early if they aren’t entirely needed, ceding to these requests will open up the door to more, and therefore maintaining that appearance of complete control is a necessity for the Elite. Brae, however, is still too young and naive to understand these aspects of control and power. We do, however, see her mind turning, trying to comprehend the insane facets of the world which quite literally make no sense if we were to have everyone’s best interest at heart, and not just that of the Elite. Yet, as the novel progresses, we will see her further understanding and disenfranchisement with these structures, perhaps due to the Reverend’s story, or perhaps due to something inside herself.

In walks Uncle Lomax, or Lomax LeSpark, brother to both J. Wade and Ives LeSpark, brother-in-law to Elizabeth LeSpark, and Uncle to Pitt, Pliny, Brae, and Ethelmer. Lomax owns a factory which makes something known as Philadelphia Soap, or as many in the area call it, Anti-Soap. Rather than cleaning whatever body it attempts to clean, this Anti-Soap, upon contact with any form of moisture, “becomes a vile Mucus that refuses to be held in any sort of grip […] and often leaves things dirtier than they were before its application” (47). He is thus the perfect analog for the coming chapters — being a producer of an entirely useless, mass-produced product which is sold as something that will clean things up and make them better, when in reality all it will do is leave behind more scum than there may have been before. A parallel to the colonized destination that the Astronomers will soon be arriving at.

We start this chapter of the main story with Cherrycoke belowdecks with Unchleigh, the man who went up the mast with Bodine to scout the l’Grand (1.4). He, along with Mason and Dixon, are upon the Seahorse, manned by a new Captain, which is now in convoy with a larger frigate, known as the Brilliant, 36, that could provide protection if needed. Unchleigh is among men who discount the benefits of possible Civil Unrest, stating that Print and Coffee-Houses are what cause this unrest. And he is not wrong, for Print is the means by which theoretical and revolutionary thought can be transcribed, and a so-called Third-Place like a Coffee-House is where that information can be disseminated. Among this talk, the Reverend — a potential revolutionary mind — has an ‘inward lament.’ Cherrycoke pines to return to a Cross-Roads, where choices of ‘paths taken’ can be remade. The crossroads is a diverse symbol, which can be read as a historical branch-point: one in which a pointsman2 has complete control of. The Reverend’s hope is thus to return to the point in his life that switched his own historical trajectory, choosing instead of posting up the revelatory fliers to doing something less overtly revolutionary that could incite understanding while not landing him in exile. Or, even not doing anything at all. That is Their desire — that with the punitive measures taken against more benign actions of revolution such as this, the likelihood of them reoccurring (or even better, the likelihood of non-benign actions occurring at all) would be rendered entirely extraneous.

The new captain of the Seahorse is one Captain Grant, and he may quite literally be insane (though more on that in a second). As the two ships move on in tandem, Grant tries to pass the time by pretending to ram the Brilliant, 36, which in turns pretends to prepare for battle. The ships, in the open sea with no one around to save them if something goes wrong, begin to play chicken while Mason and Dixon watch, lamenting about the insanity of what is going on. And, as it turns out, some other insanity is going on behind the scenes regarding “a mysterious seal’d Dispatch” that was given to the Captain upon leaving Plymouth which would direct them only “as far East” (50). In other words, the Royal Society has actually changed their mind on where the two Astronomers would be headed. It therefore turns out that their original request would in fact be fulfilled because the RS realizes that an arrival at Bencoolen in Sumatra would likely lead to capture or possible death, and thus the failure of the R.S.’s goals as a whole. However, as previously stated (1.5, and in this chapter), while the Society may fully agree with Mason and Dixon’s perspective, They could never allow the grand plans of the Society to be amended by two measly underlings. Or, at least, They could never let the underlings and any who may hear about it know that this is why the plans were changed. And thus, the Astronomers sing, continuing their lamentations, cursing the Society for treating them as slaves in that someone in a position such as theirs could only hope get their work from nobody except those with immense wealth. They realize that scenarios like this will occur again and again as long as they work.

Captain Grant, previous to being captain of the Seahorse, was waiting for any ship that he could take under his command. However, despite his initial qualms with manning a ship as lowly and broken down as the Seahorse, he eventually relented. One Admiralty Fopling gave him the above-mentioned letter and told him not to open it until Tenerife, one of the Canary Islands off of the coast of Morocco which, ironically, was not a territory of Morocco, but which had been a Spanish Colony for nearly the past 300 years. Grant is anxious given the original destination of the Seahorse was to be Bencoolen, and he wonders if the new destination, not to be revealed until Tenerife when it would be too late to turn back, would be somewhere equally or even close to as dangerous. The Admiral basically says, ‘Oh well, not my concern!’ Though a musing goes on, stating that “so much more swiftly than the Trade Winds, these Days, do the Winds of Diplomacy blow” (51). The colonies are spreading; whether it be Tenerife, Bencoolen, the entirety of Indonesia and Sumatra, or the actual yet-to-be-stated destination of the Seahorse, the Empires have spread their people wide and far, claiming already inhabited lands for their own colonies to act as two things: a means for accumulation of resources, be that inanimate product or slaves, and a playground in which they can do as they will without repercussion.

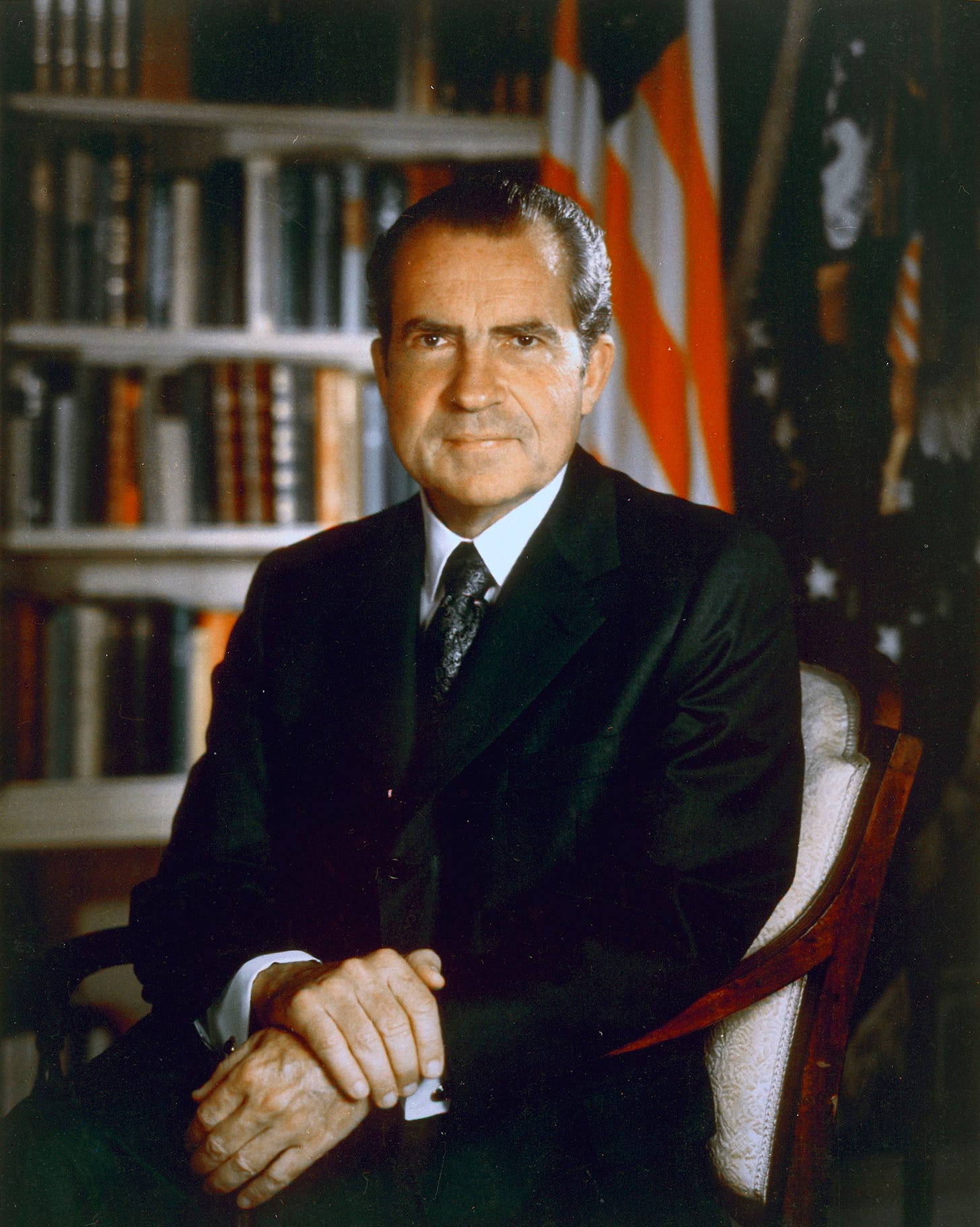

Despite his qualms, Captain Grant takes the letter and the ship. He pretends to fire at the Admiral, and we learn that much of his shtick is “pretending to be insane, thus deriving an Advantage over any unsure as to which side of Reason he may actually stand upon” (51) — the reason he decided to play chicken with a vessel as comparatively powerful as the Brilliant. Treading that line ironically allows for more safety in this world, given if he were to appear perfectly in possession of his faculties, he may be (just like Mason and Dixon are) asked to succumb to Their will and complete tasks which are both beyond what he desires, and which may be far more detrimental to his livelihood. On top of this, an appearance of insanity calls to mind one Richard Nixon, in that “according to his chief of staff, [he] once talked about acting irrational in order to gain an advantage in negotiations with North Vietnam” (Biebel, 31).3 If a foreign body, or even the governmental body of one’s own land, were to believe a person irrational and insane, any sort of provocation toward this proclaimed ‘madman’ would have to go through more channels than it initially would have. Similarly to how Nixon may have presented as insane in order to prevent any foreign attacks on or negative policies in regard to the US, Grant is doing the same but in regard to his position as Captain.

As Tenerife comes into view, Grant views Mason in a scene that we will see repeat a few times throughout the novel: keeping vigil on an anniversary of his wife Rebekah’s passing. As we learned during the scene with the Learnèd English Dog, Rebekah is the reason why Mason’s slight disenfranchisement with the sciences occurred, and why he now is attempting to find solace in the spiritual realms or at least force himself to believe that the spiritual is as present as the corporeal. Due to his vigils, the crew deems him as — or at least close to as — insane as Captain Grant. The difference here is while Grant is using his apparent insanity for his own gain, Mason is only being observed as insane due to his divergence from the norm.

Upon these vessels of war, run by men feigning insanity in order to excuse their actions, lives an entire lineage of men who won’t be remembered by history, just as the riders of the ‘train’ or those who live solitarily in the colonies will not be remembered. In this case, we see the Seahorse’s Military Band as an analog for those men of history. When time passes and history moves on, members will depart, though no matter when or where they leave, they will forever be known as ‘musicians’ of that specific vessel. During wartimes, as with the l’Grand, when old members reboard or when new members join, “Amid the Blasts, the heavy tun’d Whirrs of enemy Shot, the mortal Cries, could the Instruments ever be heard” (53). Their voices, laments, complaints, cries, and all that they say, will be heard over the war’s crashing, but the war is all that will be remembered. Among these men is where the real life resides, for it is the common life unlike the life lived by the Elite. And because of that, it is not too rare to find Royalty wanting, at times, to live among the common man. Just as we saw Thanatz find solace and understanding among the Preterite (Gravity’s Rainbow, 4.5), we also now see “a Royal Artilleryman […] in a Sailor’s Haunt […] surrounded by them who must be both Gunners and Seamen,— hoping, I confess, to pass as one of them” (53). These Elite will imbibe in the same drink and learn the stories of the ‘musicians’ who are only remembered by their own clan. And through spending time with men such as these, these Royal men may learn to appreciate what it means to be Preterite. For each man has their own odd story, their own history, and their own nuance that will never be told in books of history but are just as enthralling or ludicrous as those told within, and far less destructive. This, however, is not a common thread, for most of the Elite will prefer to remain on their throne, never to interact with those below Them.

Having passed Tenerife, the Seahorse now moves on past the equator. We learn of the man holding everything together upon the ship, though one who often goes, like the military band, unrecognized and unnoticed: the Boatswain, Mr. Higgs. Rearranging his name to Higgs Boatswain, he is reminiscent of the Higgs-Boson: the God Particle in quantum physics. Mr. Higgs, almost literally tying things together upon the ship, acts exactly like the Higgs-Boson. Before scientists had discovered the Higgs-Boson, they had theorized its existence. In the 1960s, it was theorized that in order for certain elementary particles such as quarks to have any mass whatsoever, the Higgs-Boson would need to exist. The issue is that the Higgs-Boson had never once been observed or recorded in any sort of experiment, so its existence was unknown beyond theorization. But without it, and thus without any real theoretical explanation for why something such as the quark or the electron had mass, this would in turn render our then current understanding of particle physics impossible. It wasn’t until 40 years after the hypothesis of this particle that it was finally discovered experimentally. Similarly, our Mr. Higgs, Boatswain, made the entirety of the boat’s operation possible with his “Lashings, Seizings, [and] the art of making a Turk’s Head” (55) — in other words the knots he ties to literally ‘tie it all together.’ Without him, despite how small his job may seem over the grand scheme of things, the entire functioning of the boat would fall apart. Nothing would work as it should. And despite his importance, very few even notice his presence. That is, except “as to provide a source of Amusement for the Captain, who finds him an ideal Subject to practice being insane upon” (54). As we have discussed, pretending to be a madman allows the men in charge to do as they will while having an excuse, and practicing one’s ‘insanity’ on someone as important as our Higgs-Boson counterpart would allow the supposedly insane leader to control the ship (or the World) without having the actual qualifications or insights. It would, instead, just as the Royal Society is doing with Mason and Dixon, be acting as a pointsman, switching the world’s trajectory and history’s branch points by controlling the ‘train’ and the ‘riders of the train’.

As the Equator is crossed, as things begin to heat up given the Southern Hemisphere is in Summer at the moment, and as the riders of the boat begin to perform odd theatrics, the picture of this entire chapter becomes clear. The boat has been set out as a microcosm for our modern world and the world of the mid-1700s. The boat, and our world, are run by leaders who know exactly what they are doing. Yet, they are feigning insanity in order to take advantage of their place of power while removing the blame from whatever their more evil intentions may be. And the people who they are controlling — the riders of the boat, the riders of the train, or the Preterite of the Earth — are defined only by their place on this Earth. They are ‘The Military Band’ who will be known for where they are from and nothing else, while the wars that surround them and those who started the wars will be written about in history books. And with all of that, we learn that the world is only held together by men like this who will never be remembered; for, without the Preterite, the worker, the or the citizen, all the knots would go untied and the world would fall apart. Yet, the man who abuses this system is the one who will be considered great.

The scene shifts back to the home of the LeSparks where Pitt and Pliny are asking, “Did somebody make it a crime to cross the Equator” (56). Uncle Ives, the father of Ethelmer and brother of J. Wade and Lomax, states that crossing the Equator is simply an “Abstraction that cannot even be seen” (56). Ives, however, is ignorant of what borders could mean, for while yes, they are entirely abstract concepts created by humanity to divide geopolitical lines, crossing them could also entail “Tolls exacted for passage thro’ the Gate of the single shadowless moment” (56). Because while passing them should be the same as walking down a path in a park, or crossing from concrete to grass, the powers-that-be such as the insane captains of ships and our Elite leaders have instead designed it to extract our freedom and wealth if we were to cross when we were not supposed to. And on top of the politics behind borders, travelling South of the Equator is now meant to equate to travelling South of the Mason-Dixon Line, showing that one who does this would then witness “all-unforeseen ways of living and dying” (56): a way of life entirely unknown to them where whatever freedom one may have had would thus be proven to have been given by the ‘grace’ of the Elite, and is something that could easily be stripped away if one were merely of a different race or class than the ruling class’s cohort. Unsurprisingly, it is the Reverend making these statements about the reality of crossing borders — again given he is at least a somewhat revolutionary figure. And Cherrycoke finishes his lesson on borders by drawing the attention away from the more explicit revelation he is trying to make (because remember, he is in the home of the Military Industrial Complex’s forerunner) and is now trying to get that same message across in ways more comprehensible to children while remaining abstract to the adults. To do this, he shows the implications of having ‘Spotted-Dick’ (an odd raisin-filled British pudding) thrown in one’s face. Yes, much of it will just cause a mild inconvenience, but the pieces that cross areas that should not be crossed — such as when “it goes up your Nose” (56) — well, that is when the body will begin to fight back.

Back on the Seahorse one last time, we hear of the Trade Wind’s blowing. Biebel states that the wind, which comes off of the African continent, is coming from “the continent of human origins and often the site of colonization and oppression” (Biebel, 32). Because of this, he proposes that those upon the ship are now viewing themselves as returning to their own origin in order to assist what they would consider the ‘unevolved’ homo sapiens to achieve a civilized society. And yes, that is exactly what is happening, for the Astronomers, not even being a truly Elite class but merely those who help purvey the Elites’ goals, play a game of sexual fantasy. Dixon is not an evil man by any stretch, but he has been raised into believing that the women of these foreign lands will be beautiful and willing to do whatever he so desires. Mason would likely believe similarly, though cannot fathom it due to the love he still holds for his late wife, Rebekah. But these are mere fantasies in the minds of two men long at sea, imagining love and conquest as a game. The figures, the ‘phantasms,’ “enjoy private lives […] ever safe from the Insults of Time” (57). While the real and tangible people within these continents, and even those who aren’t nearly as oppressed, are not safe from these white men’s wishes, at least the imagined spirits are sheltered from the ‘insults of time.’

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 7.1 (Chapter 7 is a longer one, so I’ll be splitting it into two parts. I hope not to do this too often. We will make it nearly to the end of page 66 (about 2 lines from the bottom), finishing on the line “are quite us’d to even less inhibited Displays.”

Remember, her name means the coming darkness. Or, to analyze it a bit: she, as a daughter of the military industrial man, will see flaws in the story, flaws in her ‘father,’ and flaws in America; yet her hope may slowly die out as the candles in Tenebræ will (1.1).

If you have not followed along with the Gravity’s Rainbow analysis, a pointsman (also known as a switchman) is the person who pulls the lever which switches the tracks of a train. This idea is used as a metaphor for the Elite who control history. They are able to simply ‘pull a switch’ which will switch the tracks of history and thus alter the live of the ‘riders of the train’ — also known as: us, the Preterite.

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.