Mason & Dixon - Part 1 - Chapter 5: An Invisible Face

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 1 - Chapter 5: Discussions at Plymouth, the Letter to the Royal Society, a Letter of Reprimand

When Mason and Dixon first met (1.3), they only learned select things about one another. Through their slightly awkward conversations, they learned of each other’s superficial desires along with how they interact with the world around them; however, it wasn’t until the Seahorse was attacked that either of them truly knew the moral and situational fiber of their being. Each very well may speak what they believe or hide what they think is necessary to hide, but it is not until a moment where one is surrounded by death and danger where one’s true character will arise. They both now know “exactly how brave and how cowardly the other was when the crisis came” (42).

They discuss Dixon’s former Quakerism before he was expelled for drinking excessively and keeping company which the church did not consider suitable. He also states that others have been expelled from the church due to “working for the Royal Society” (43). What we are seeing is the level of power which certain institutions hold over the lives of their members, and the control which they can so easily implement. Obviously, Dixon’s expulsion from the Quakers does not seem something all that dire to him, yet it sets the stage for what these institutions can get away with. If the Quakers can remove you from their practice for socializing with undesirables, what could a more powerful governing body do? Nonetheless, even realizing that writing to the Royal Society is writing to one of those far more powerful governing bodies, the two begin to compose a letter questioning and partially accusing the Royal Society of either hiding information or being malicious in their intentions. They wonder how it is possible that the notion of attack could have gone unpredicted and what potential reason exists in that a French ship would attack an English ship of quite literally no threat. Dixon’s expulsion from the Quakers, and the both of their already disenfranchised view of the Royal Society’s inner-workings, introduces the idea that neither of the two will be all that deferential or obedient to the powers that be — a sort of parallel to many of Pynchon’s other main characters being disenfranchised with their leaders: Slothrop or the those who formed the Counterforce in Gravity’s Rainbow, or those like Oedipa Maas, Doc Sportello, and Zoyd Wheeler in his California novels. While many of these characters are working for the system which is oppressing them, they are well aware of that fact and are usually only doing so out of necessity, not out of any nefarious intentions.

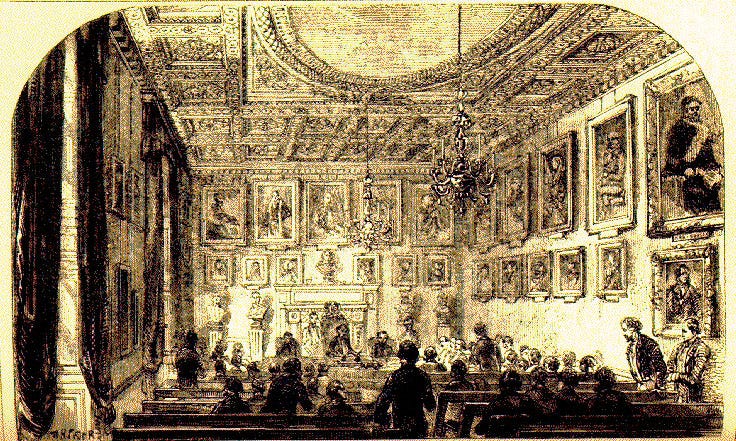

Moments go on, punctuated by their paranoid conversations and their paranoid silences. They speak, then take a break to smoke, and eventually speak again. Each time they try to understand more and more about what may have happened in regard to the recent attack. Eventually, the letter that they compose shows their wariness at continuing along a path so destined for failure and possible death. But the Royal Society responds, saying, “their refusal to proceed upon this voyage after their having so publickly and notoriously ingaged in it, will be a Reproach to the Nation in General, […] [and] in the case they shall persist in their refusal […] they may assure themselves of being treated by the Council with the most inflexible Resentment, and prosecuted with the utmost Severity of Law” (Heindel, 1939).1 Notice the use of the word ‘their’ as opposed to ‘your’ despite the letter being directly addressed to Mason and Dixon, as well as the lack of a complimentary close or signature. It is written as if being a direct statement to the World by “some faceless committee” (45). Even though their letter was originally addressed to Bradley, the Royal Astronomer who Mason was assistant to, the reply comes from this faceless committee with no hint of knowing or familiarity, just pure bureaucracy.

This is how the system is built. We may have friends in high places whose faces we know — or acquaintances at least. And if we do not, then we at least have those we can go to for help. If one has proximity to or representation by one of these individuals — say to a legislator in a state one lives in, a manager or owner of a business, or anything else of that sort — it is understood that, in a time of need or simply because one seeks to alleviate themselves from some ill, services or advice could be requested. Much of the time, this help would be granted, or a promise would be made that they are ‘working on it’. That is, until the request became a disservice, an inconvenience, or an outright attack on Them (the Royal Society). When that occurs, the person or body of governance that you once thought had power will have anything but. The letter will be passed down the line to the appropriate new level of power, rising in the ranks as faces become blanker and more obscured. At some point, we do not know who these members of the ‘Royal Society’ are. They are hidden away among layers of purposeful obfuscation, ready and willing to punish with the ‘utmost Severity of Law’ — or, if They do not want word getting out, with the utmost Severity of whatever other means are at Their disposal. It is impossible to remove oneself from this system.

As a worker, you may do something as simple as request a day off. Sure, under many circumstances, that could be granted. But what if your demand as a worker begins to seek freedom for your class as a whole? What if that day off, granted or not, turns into an order from all working-class people desiring more freedom from their exploitation? That is when the Royal Society steps in to quell the People. There will be no specific face telling you what the outcome of leading this fight will be, just a blank expression, a letter with no name, and the threat of prosecution, punishment, or worse.

Our choices are innumerable — to fight back, to relent, to proceed using quieter means, to compromise, to reduce what one is asking. There is “no single Destiny, […] but rather a choice among a great many possible ones, their number steadily diminishing each time a Choice be made, till at last ‘reduc’d,’ to the events that do happen to us, as we pass among ’em, thro’ Time unredeemable” (45). Or, in other words, whatever that single choice we make out of those innumerable options is, will in the future reduce the other possible outcomes. If we relent to their demand, the options of ‘fighting back’ will diminish in potential every time the opportunity arises again. The lens that captures the light of a hundred-thousand stars will watch as each one diminishes, as the fire of the universe winks out because we were too afraid of the dark — of the faceless beings who threatened us with death.

The two now know that there is no hope at proceeding by any other means than following orders. They chose the option of relenting just as we so often do. Blame cannot be placed upon them just yet, for they have not seen enough to say for certain that their paranoia is anything but just that. Nonetheless, a star is extinguished, a historical turning point is chosen, and a path is closed off. But how many paths can someone close off before we are to ask if blame is now deserved? or if the answer is now so clear, that one is clearly acting to preserve oneself? Time and time again we will see answers become clearer, and the decision for when blame is deserved is up to you to decide. But it cannot be withheld forever.

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 6

Heindel, R. H. (1939). An Early Episode in the Career of Mason and Dixon. Pennsylvania History, Official Organ of The Pennsylvania Historical Association, 6(1).

I have only partially quoted this letter for the analysis. The link below will show both the full letter along with the one composed by Mason and Dixon which the Royal Society was responding to.