Mason & Dixon - Part 1 - Chapter 4: Mutual Extortion

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 1 - Chapter 4: Ethelmer, Captain Smith's Boarding Fee, Attacked by the l'Grand, Invisible Gamesters

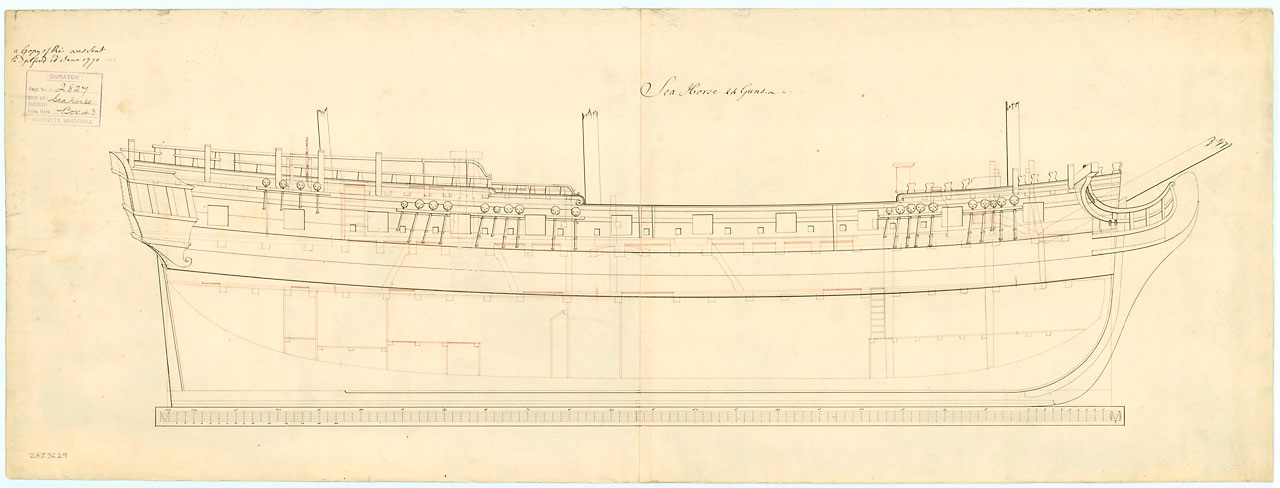

We are back in the house of the LeSpark’s, or in other words, back in the America that was formed from Mason and Dixon’s quest — the America which is now presenting the history of those two men for better or worse. Revd Wicks Cherrycoke is the one still telling the story, only being allowed to stay in the home of the LeSparks if he tells it like the Elite believe it should be told. We earlier learned that after posting up anonymous fliers around the city revealing the crimes of people, Cherrycoke was punished by being sent into exile upon a frigate known as the Seahorse manned by Captain Smith, headed ‘East’ (1.1). This happens to be the exact ship on which Mason and Dixon will soon board, headed (apparently) to Sumatra. So, while the previous chapter is told through a series of lenses which the Revd was not truly able to verify, this one is told through a more verifiable perspective (that is, if he is telling the full truth). He is starting this part with a hook via some foreshadowing, hinting at the fact that the Seahorse will soon be attacked by the French, just as Hepsie predicted.

Joining the listeners now is Cousin Ethelmer, appearing randomly one day, back from college at, though it isn’t explicitly stated, Princeton. Ethelmer is the son of Ives LeSpark who we earlier learned was the brother of J. Wade LeSpark (1.1), thus making Ethelmer J. Wade’s nephew. He is an Ivy Leaguer, just as Slothrop would be 150 years in the future, and so likely represents something similar. However, whereas Slothrop was only seen after his indoctrination into the world of intelligence agencies via the Ivy Leagues, Ethelmer is currently in the midst of his schooling. Obviously, Ivy Leagues in the 18th-century did not hold the same trajectory of purpose that they often do in the 20th- and 21st-centuries; however, they still were a place where those within the realm of the Elite could collude and fraternize or even join potentially ‘secret societies.’ This does not impose an evil connotation upon how Ethelmer should be read, he is merely on the foothills of evil’s origin, or at least where many people in that realm will originate. So, he should be interpreted as someone who is misguided and both potentially salvageable and irredeemable depending on the path he takes forward. He would be like Slothrop who, at the time of his schooling, did not realize what path he was being led toward, and so cannot fully be blamed for any misbeliefs he may have just yet. Interestingly, also being nephew of J. Wade LeSpark removes him from being an inheritor of wealth from the Military Industrial man but still keeps him within the family. Therefore, he is influenced by the desires of that family but is not driven to maintain their aims and objectives since he knows he is not the direct inheritor of their dynasty.

Being a college student, Ivy League or not, Ethelmer does have a pretty specific thing on his mind — women. And so, he begins his flirtation and showmanship in an attempt to woo Tenebræ. To do this, he pokes fun at the fact that those like Cherrycoke and LeSpark prefer tales which are calm and don’t set their heart afire. The irony is that while J. Wade LeSpark may want stories to be told without too much cultural criticism on the colonizers since that would incite an understanding of the evil they committed, he “made his Fortune years before the War, selling weapons to French and British, Settlers and Indians alike,— Knives, Tomahawks, Rifles, Hand-Cannons in the old Dutch Style, Grenades, small Bombs” (31).1 Therefore, given that this is how J. Wade LeSpark made his immense wealth, he is a precursor to the Military Industrial Complex. Just as during WWII Shell sold and helped launch weapons for various sides of the war (to both the Axis and Ally powers), LeSpark did not have any true loyalties except to profit for himself, selling weapons to any side independent of which side he was ostensibly on. Thus, his home, a representation of America, is built on this type of industry, this lack of loyalty, and on the pure interest of capital alone. So yes, he may be a traditionalist in the sense that he doesn’t want his children to hear stories that get them too hot-headed about the real state of America. But look beneath the surface a bit to see which project he may be grooming them to continue. Things that stir the emotions of the average citizen are not all too good for Their purposes. Either way, Ethelmer is more than happy to make some light-hearted jabs such as this in order to flirt (especially if it’s with the character who is already more aware of the evils at hand), but in reality, he gains quite a bit from his proximity with Uncle LeSpark, and so doesn’t stir the pot too much. I mean, what better friendship could there be than a Military Industrial man and an Ivy League student ready to make his way in the world?

The story moves back to Mason and Dixon now getting ready to board the Seahorse. But there’s a slight hitch. The captain, Captain Smith, wants them to pay an absurd sum of money to board and be taken to Sumatra, most likely doing so knowing that the two are fully funded by the Royal Society and that this society would pay just about anything to get the information they needed. So, while Mason and Dixon may be peeved, and while the reader may initially infer that the captain is incredibly greedy, he really is just a man trying to make it by taking a little bit extra from a group that can more than afford it. So, can we really blame him?

The scene quickly cuts to the society trying to figure out what they’re going to do about this qualm. Ironically, these wealthy men in white powdered wigs claim that Smith’s fee is “not to be easily distinguish’d from petty Extortion” (32). And so, in the end, they send a letter back to Captain Smith accusing him of this extortion. In order to save face, Smith makes an obviously fake apology meant to please Mason and Dixon and thus the Lords who were so peeved at the Royal Court. While Dixon seems ready to accept his apology (given his more lackadaisical, carefree nature), Mason immediately begins his accusations: “Saintly of you, considering your Screams could be heard out past the Isle of Wight” (33). However, Smith and Dixon convince Mason to settle down, and a deal is made that ensures the Navy itself will help fund the travel.

About to head out, “On the eighth of December the Captain has an Express from Admiralty, ordering him not to sail” (33). It is revealed that their destination, Bencoolen (a territory on the coast of Sumatra), has been captured by the French. And as we know from Hepsie’s prophecy, the French have been a bit gung-ho about capturing British ships nowadays, so heading there may not be the best idea. Captain Smith states that they will in fact continue to sail, hoping that by the time they make it to the Cape of Good Hope (today known as Cape Town, South Africa), the order is removed. However, this makes the lot of them feel rather paranoid. If the Society knew that Bencoolen had been taken by the French, then was this expedition purposefully destined to fail from the get-go? Or at least to never to make it to sea? Mason’s question, however, does give a hint about what is going to happen: wondering, why is there not a team of observers heading to the Cape of Good Hope in the first place?

The Seahorse disembarks, travelling West from Portsmouth through the English Channel while sailors and men aboard the ship discuss the precariousness of travel. Nonetheless, they believe that Captain Smith must have some skills at sailing given he’s been around for so long. Because of their surety, they proceed to sing a song about the land they are bound for: Sumatra — “Where girls all look like Cleo- / Pat-tra, / And when you’re done you’ll simply / Barter ’er, / For yet another twice as / Hot” (34). Indonesia, thus Sumatra, is and was a heavily colonized land for a long period of history, and one thing which the White Man loves to fetishize is the exotic nature of dark-skinned women in foreign lands. Their song, therefore, is a call to what many men aboard the ship are looking forward to: not scientific discovery, not even the furtherance of one’s country’s power abroad, but to that consequenceless playground that a nation’s colonies are so known for, where women are as ‘unique’ as they are ‘barterable’ and ‘useable.’

Captain Smith, though his crew seems hopeful in his abilities, is not all too happy about being captain of this vessel. It was assigned to him against his will, the ship being a sixth rate: and “Sixth rate is the smallest rated class” (Biebel, 25). Thus, it is almost an insult for someone who believes himself to be a great captain to be given such a paltry vessel, especially one that in its past was used for what amounts to diversionary tactics “under the French batteries of Beauport” (35), or one that is known colloquially as the Jackass Frigate. But not just this: insult upon insult proceeds to find him. For, as he stands atop the ship, a random sailor named possibly the stupidest name imaginable, ‘Blinky,’ tells him “you’ve got a good job,— don’t fuck up” (35). And while he does not respond sharply as a captain typically would, we learn (via Cherrycoke’s discourse with the Astronomers) that Captain Smith simply wants to be taken seriously — wants to be known as a Man of Science and to be recommended to the Royal Society in order to perhaps be granted more respectable ships to sail. He is insecure, and like anyone trying to make it in an ever-expanding world, simply yearns to be taken seriously, to be respected, and to live comfortably. Maybe this is why the sailors and captains alike have these tendencies toward colonial expansion and fetishization. Not that it is an excuse for their actions, but it gives sense to this evil as this is the one iota of respect and power they can ever come across. And thus, perhaps the Royal Society itself forces these needs upon them by balancing their desire for power and their attainment of power on a thin razor’s edge so that these men possess those evil tendencies — so they are willing to go as far as they do to gain power by whatever ghastly means they can find.

While travelling across the English Channel, the l’Grand, a French ship — the one which Hepsie had warned them about — is sighted. So, to prove both his bravery and his scientific prowess, Smith prepares for battle and sets the crew to work. He calls the first two sailors (notably White European sailors), Unchleigh and Fender-Belly Bodine, to climb the mast “with a watch a compass,— and if it proves to be a sail,” (36) to attain some bearings. However, the third sailor who he calls, an Indian man named Bongo, is given other instructions. Bongo is called like a dog — “Here then, Bongo! Yes!” — and then is given alternate, not too ‘scientific’ instructions — “Yes, Captain wishes Excellent Bongo smell Wind!” (37). Or, in other words, while the White European is tasked with finding the coordinates and veracity of the French ship’s position, the foreigner is treated like an animal — tasked with using animal senses to verify the same thing. Oddly enough, Bongo is far quicker and more successful than Bodine and Unchleigh; the magic of the old-world still seems to have more power than the science of the new. So, while he is treated as an animal, spoken to as one, and told to do as one does, he is nonetheless more in tune with the very nature of the Earth. When Bodine and Unchleigh finally come to the same assessment, the ship is already responding to Bongo’s call.

And with battle unfolding, the Astronomers are asked to go belowdecks: basically, to get the fuck out of the way.

Back at the LeSpark’s home, Cherrycoke embellishes the story just a bit so to entertain Pitt and Pliny, speaking about the “blasting! and smashing! and masts falling down!” (37). While J. Wade LeSpark’s greedy, power- and capital-hungry eyes are likely gleaming at this aspect of the story, believing his sons are being (though he would use a less connotative word) fully ‘brainwashed’ with this scene, Cherrycoke likely sees this as another opportunity — one to show them tales of bravery and of humanity’s elevation above mere individuality: tales of survival amongst Death — where the individual forgets his own mortality for a moment in the hopes that he can save another, performing surgeries and suturings at sea while death is imminent at every cannon fire. Incessantly, Cherrycoke spoke of “dying, nausea, Speechlessness, Sweat pouring” (38). It is a story told like a modern-day action-adventure novel, keeping the suspense at its height, though leading us to question whether this type of story is something that gives the children (the future generations) hope against Death or an imprudent impulse to confront it.

The battle rages on upon the ship and Mason and Dixon lie “Below-decks, reduced to nerves,” (39) watching as sailors were brought down with dire wounds, feeling entirely useless among so much death. But the Captain asks the question that really may be setting the Astronomers at unease: “Are you two really that important?” (39). Well, it depends which perspective we’re looking at. Because no, there likely is not an ethical reason that the brutal death of thirty men could be worth a single furtherance of science. And Mason and Dixon, despite being men of science, have so far been characterized to have at least some hint of a moral compass. They are aware that the lengths the Royal Society is willing to go to — to allow death to curse their people, to spend unnecessarily large sums of money that could go to whatever other noble purposes — proves that the end goal would have far more wide-reaching intentions than the mere furtherance of our understanding of the cosmos. Something else out there must be worth whatever gain they may procure. Venus’ coming transit holds meaning in the realm of science and magic, but also to that of Capital and Power.

Oddly, the French ship stops the attack. The Commandant (the Captain of the l’Grand) even comes aboard to have a conversation with Smith. This attack and retreat both came out of nowhere, forcing the reader and those aboard to ship to question if there were no other intentions or reasons for such an attack. But what could they be? It is not the first time where oddities or coincidences make themselves fully seen to all willing to look, and while it is entirely possible that the attack was just an attack, after so many of these coincidences occur in the later pages, it will become quite clear to the two astronomers that something is afoot.

Unable to pursue the French ship, the Seahorse docks in Plymouth, a port on the very Southwest end of England, at the very edge of the English Channel right before the ship will begin travelling South. More information is revealed: that the l’Grand itself was known to be suffering from low morale and a paltry number of guns. Thus, the scrap between two lesser ships, along with “Invisible Gamesters who wager daily upon the doings of Commerce and Government” (40) heavily calls to mind the cockfights at the bars in Portsmouth (1.3), but on the scale that the Elite prefer to bet on. So, while those cockfights did have hints of darkness within them, their stakes were the lives of chickens, which obviously is not to discount the fact that such animal cruelty is something to be dismissed, but it is nowhere near the wide-scale death and destruction that such naval warfare would lead to, nor the insane wealth to be derived from betting on or funding this warfare. And if the parallel between the cockfight gambling and the warfare gambling can be made, then what is the analog to the labyrinth of hallways at the back of the barroom where sounds of ‘pleasure’ could be heard but not seen?

Finally, Mason and Dixon confer once docked, going over the numerous paranoias they encountered just this day. Most importantly, if “They knew the French had Bencoolen,— what else did they know?” (41). If the lives of the sailors are expendable, even desired if it makes the Invisible Gamesters enough winnings, then why would the Astronomers’ lives be any less so? In order to drown out this paranoia, “They pass the Bottle back and forth, and when it is empty, they throw it in the Sea, and open another” (41).

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 5

Despite me talking about how he was an arms dealer in 1.1, this is actually the first time it is mentioned. I just felt it was vital to mention back then to set up the Frame Story correctly.

Really enjoying your analysis (M&D is my second-favorite Pynchon novel, tied with ATD). Can we hear more about Rev. Cherrycoke as an unreliable narrator, please, and how that impacts our understanding of M&D? I've always struggled to make sense of that character and his role in the telling of the story.

Nice call on the ship battle paralleling the cockfights...hadn't thought of that. Brutal.