Gravity's Rainbow - Part 1 - Chapter 3: Coffee, Paperclips, Heat Maps

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 1 - Chapter 3: Teddy Bloat and Slothrop's Desk

Before he reaches his destination, Teddy Bloat, one last time, finds himself with the remnants of the glowing consumer lifestyle, now instead of shiny aisles filled with neatly stacked variations of produce or clean containers, it has become the filthy, cheaply made product, never lasting more than it was intended to last, wrapped in a substance made from another derivative of petroleum. Our modern life and work is rendered possible by shitty products sealed in alchemized oil.

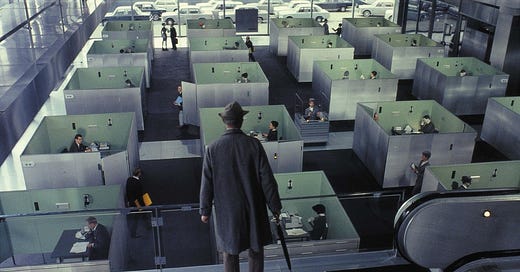

He is on a mission today — a quiet afternoon, finally, not filled with sounds of war but, instead, with those of birds and nature. Hidden away in these quiet environs are "a million bureaucrats […] diligently plotting death[,] and some of them even know it" (17). This chapter briefly concerns itself with the horrors of intelligence agencies — their motives hidden away in the back-alleys of paper-based bureaucracy, a silent death within a silent life, the pacified adenoid hiding away the evil that was once on the surface of things.

A picture is created for us: unobservant office workers sitting around day drinking, your stereotypical secretary obliviously and cutely stationed behind a desk to give the employees someone to flirt or chat with, each and every person looking at least somewhat alike, names unknown or forgotten, all coming from this or that prestigious Ivy League. They are the creators, consciously or unconsciously, of the New World: "the slummakers of war" working on "typewriters tall as grave markers" (17). Whether they know it or not, those typewriters are sending and have sent many to their own graves, yet the scene itself poses no hint of sin or iniquity. It is a simple panorama of the prototypical Western Workplace, where our middle-class heroes go to protect us from threats both foreign and domestic.

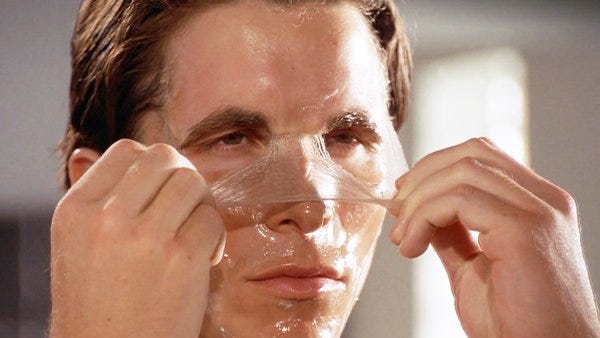

Bloat has arrived to spy on one Lt. Tyrone Slothrop (who, if you haven’t read this novel before, is someone you should pay immense attention to). Tyrone’s desk is a mosaic of the worlds hidden within the bureaucratic system — we begin by reading of pencil shavings, paperclips, different caffeinated beverages, cigarette scrap, and random pieces of junk. The reader’s, or observer’s, mind wanders as the list grows and they may briefly miss the quick glimpses of the office’s true purpose — maybe those more literal ones like the "few old Weekly Intelligence Summaries from G-2" or the symbolic "distant cloud [with] the orange nimbus of an explosion (perhaps a sunset)" (18) or perhaps not.

Bloat photographs an odd map that Slothrop has tacked up on the wall, drops his camera back in his bag, and is on his way. The map geographically catalogues encounters that Lt. Slothrop has had with women ever since he began going out searching for rocket disasters. As we discover later, these same sexual encounters are exactly where V2 rockets have dropped, shortly after he left. The correlation though, at this point in time, is simply unknown — there is a code built into them based on colors, yet the code itself is indecipherable (or, They want us to think it is). We will learn later that the code holds no meaning, that it is born purely out of the inner feelings of a single mind, but in the postmodern world that is the world of Gravity’s Rainbow, a single mind is not necessarily a thing anymore — each individual has lost their singularity. We are an amalgamation of all that is forced upon us.

Tying It Together (Chapters 1-3):

(Note: I may include sections like this occasionally, especially if the chapter itself is a shorter one as this was. These first three chapters have been rather disjointed, and connections may remain unclear. So here we go, for clarity’s sake and to build an understanding of Pynchon’s thesis as we move forward).

Let’s build it from the bottom. In three chapters, Pynchon has shown us a post-apocalyptic dream vision, an odd intelligence officer finding happiness in creature comforts derived from exploitative practices, the same officer’s ability to control the fantasies of others, and now horrifying genocidal practices held in the silent, unassuming workplace.

Pynchon’s thesis thus far is arguing that evil is hidden in plain sight, and that the simple shuffling of a piece of paper can have dire consequences. Our world is built on this paperwork. It is entirely unreal — a theater set. We have set our livelihoods and existences on the necessity to work menial office jobs. Thus, we do not question the system when we notice oddities popping up in otherwise bland places. Things, on the surface, like the placated Adenoid itself, may appear to be just another line of text in an email, another news headline that has no effect on your life, a sticker on the flesh of a piece of fruit. They have crafted this fictive world to make our lives just bearable enough, or, to those whose lives are not bearable, as those train riders in the apocalyptic vision, have stripped away any form of power or voice they may have.

Our lives being bearable, why not simply move on with the pack? Why fret about how we get our fruit, or what may be happening behind tinted windows in secure buildings on the corners of main roads, or about a giant death machine that has the ability to do harm, but just seems to be sitting there, quietly, for now? If there are colors on a map that may signify an unbearable answer to this world’s horrors, why would we delve into it, expend every ounce of brainpower we have left, and become more upset and uncomfortable at the state of things in the end? (And maybe not every puzzle has an answer, but why not look if we can?) If we have the chance to just gawk at that pretty secretary behind the front desk, or to drink with co-workers without worrying too much about what our jobs are really designed for, why do more? We’re happy, right?

Because if we don’t, we will be the train riders. We aren’t the lucky ones (at least, most of us aren’t) who will be ignoring borders, flying away from danger without a care in the world. We will be on that rickety train heading off to be stuffed in cramped rooms, awaiting Their vision of the future.

They want us to believe that true change would mean the loss of our lifestyle. What they don’t tell us is that we won’t have to give up our comforts to achieve the world of our dreams. Pirate may love the pleasures derived from consumerism, but he has created his own communal method to achieve these without stooping down to accepting exploitation or colonization as the only means to maintain his lifestyle. Pynchon, so far, has been arguing that we must look carefully — don’t just scan over the pages and take a list for what it is at the most basic level — and seek answers outside of what They want you to seek. Their worldview does not need to be our own.

(And may I argue, you need to take this same method through the rest of the novel to better understand it. Don’t read it as you would read another book. Look beyond the typical literary analysis. Get weird with it. You may not always be right, per se, but if you go about it critically and with a good heart, you’ll never be wrong).

Two major things to note before next week. These first three chapters have been largely based on the more literal political analysis, which may turn a lot of people off. I’d like to first say that you need to understand these ideas before you look at the more individually human side of things, which is why I started so hard on the politics, conspiracy, and condemnation of capitalism and greed. I will maintain these ideas throughout the analysis, but next week we will also begin to get more down to the human psychology of why an understanding of these political events are so damn important. What does it do to us?

Up Next will be the first half1 of Chapter 4 (top of pg. 25, ending with the words “inside a parable”), how the history of a nation’s psychology can be explored through one character.

I was going to do Chapter 4 as one long post, but it’s been the last week of work before summer break so I’m trying to maintain my sanity in the meantime.

I love the first encounter of Slothrop via the layers of detritus on his desk. For those of us who are writers, it's a technique that we can incorporate even if we lack the towering genius of Pynchon; introduce your character through a description of their objects.

I don't know if you guys like the podcast Death Is Just Around the Corner, by Michael S Judge (who his fans refer to as MSJ). One of the things he points out about Slothrop's Desk is the "dictionary of technical German." This is one of the only nods to the intense, savant-like intelligence of Tyrone Slothrop, to have such a sophisticated technical understanding of a brand-new technology in a second language. After Part I, the novel lives in the German-speaking world, and all of Slothrop's adventures would have been conducted in German. Readers, especially self-identifying males, love to identify themselves with Slothrop, but this is only possible because Slothrop's own self-image seems not to acknowledge his vast intelligence. I think it's reasonable for Pynchon himself to identify with Slothrop, but kind of arrogant for any of us normies to truly believe we see ourselves in him. Not only the intelligence, but his irresistible charm, his sexual appeal, and his wit/humor. I would give anything to hang out with him.... sigh...

The Firm really are evil: Bloat has to work on his lunch hour!

So I’ve fallen way way behind due to catching COVID and immediately afterward having to do a month-long mental health treatment, but I am still committed to this read-through!

Advice to first-time readers: don’t feel like you have to google everything, but know that the connections of even the seemingly-random stuff could fill up another book the same size as the original novel. (The Thayers were a Boston Brahmin family whose brand of health products were purchased by L’Oreal, a french cosmetics company which began as a front for nazi collaborators. The News of the World got Mick Jagger arrested and was almost bought by Ghislaine Maxwell’s dad.) Also, as Andrew writes, pay close attention to what you are told about Slothrop, what you know for sure and what you don’t, and what other characters think they know and how they know it. This line of inquiry proves deeply illuminating on re-reads. Spoilers: https://pynchonnotes.openlibhums.org/article/2867/galley/3258/download/

“Darlene” returns later to further complicate the Slothrop story, and the placement of “Alice, Dolores” in the list forecast certain, uh, “proclivities” that our protagonist ends up developing.

I always think of Slothrop’s map as an American flag and/or the state flag of the latent Raketenstadt- what could be a more perfect symbol?