Mason & Dixon - Part 1 - Chapter 19: In Search of Lost Time

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 1 - Chapter 19: The George, from Julian to Gregorian, Macclesfield and Bradley, Mason's Defense of Power, the Natives of Stolen Time

Returning home has not been kind on Mason. So far he has been separated from his friend Dixon, been questioned by various authority figures, been treated like a stranger by his two sons, and been denied presence at James Bradley’s bedside after his death. Not a thing has gone right for him since; and it’s not as if his time at Saint Helena or Cape Town were all too convivial either — for the most part, at least. Therefore, as he does when times are tough (or really, just ‘as he does’), Mason heads to a bar to get drunk — this time a bar known as The George. But even here he cannot escape talk of Bradley. And on top of that, his own morality and complicity are called into question in this same coming conversation.

The controversy being discussed is Bradley’s involvement in a change “that stole the Eleven Days right off the Calendar” (190). What the patrons are referring to is the switch from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar, the latter of which we still use today. This shift was decided upon firstly due to more accurate knowledge of solar time, specifically that the solar year was not 365.25 days, but 365.2425 days.1 And secondly, since the Julian Calendar had been used for almost 1600 years around the world, and over 1700 years in Britain, that small variation in average days per year (a variation of .0075 per year too many) thus led seasons and equinoxes to slowly shift over time to the point that, if things were to continue like this, one day summer would be winter and winter would be summer. This ‘shift’ was fixed by moving the calendar forward by the supposedly ‘lost Eleven days,’ returning the equinoxes and seasons to their original positions which would then be maintained by the introduction of the new rules.

All of this is quite a bit to explain to a bunch of angry and (though this is not a criticism) likely not too educated group of bar patrons. The only thing they see is that they went to bed on September 2nd and woke up on September 14th. Yet, even if this could be explained to them, despite its seeming superiority over that of the Julian calendar, they would likely not change their mind.

While here, Mason flashes back to the time when the calendar was incorporated in England, 1751, before he actually worked for Bradley. He remembers his father complaining about this exact thing. Taking us back to the topic of discussion between the Shelton and the Ellicott clock (1.12), neither the patrons nor his father seemed to realize how much of a construct ‘time’ really was. Losing eleven days, to Mason’s father, made it seem as if he had now become eleven days older given his birthday would be coming eleven days quicker. This is of course not true unless we were to look at time and age solely as words or definitions. Yes, semantically Mason’s father, and everyone for that matter, would reach their birthday eleven days sooner, making them older by definition. But time is moving forward at the same rate independent of our vocabulary used to represent it. If no calendars, clocks, holidays, or seasons were ever devised — if age was determined by appearance, wisdom, suns and moons, or winters past — then there would be no real difference but in name.

The same idea can be applied to borders. Natural borders such as rivers exist just like natural ‘tellings’ of time such as passing ‘cold seasons’ exist. These make sense and are tangible. But as with our development of the clock and calendar, our development of borders takes that natural realm into the abstract and purely definitional one. Walking across a river is one thing, but passing by an unmarked line only visible on maps and being subject to a wholly new set of laws and rulers could never make sense unless one were brought up to know exactly where that border lays. But if, like the calendar, those borders were changed, and if those who lived with one border their whole life must now rework their conception of that border and what lies on the other side, it would be quite jarring to realize that all of a sudden your home was in an entirely new land even if it appeared to be in the same.

And on top of that, it would be entirely more frustrating if the change of that border and that calendar was due to a religious leader some hundreds of miles away who did not even govern your land. Yes, Bradley brought the calendar to use in England, but it was all originally because of the Pope, living in the Roman Empire however far away. Just as so, England will subject America to its changing borders. This subjection was egregious in that firstly, the colonizers left England to escape its tyranny, and secondly (also more importantly), the Natives, whose land it actually was, should never have been subjected to these Elites whom they had never seen.

Though Mason cannot be fully implicated in this transition, similar to how he cannot be fully implicated in the drawing of borders just yet, he has been unknowingly a part of this system for some time. The entire point of Part 1 has been to show the emergence of Mason’s societal understanding — not exactly a full-on realization or comprehension, but a subconscious, repressed idea of what is actually going on in the world. An idea that is being slowly drawn out and becoming more and more impossible to ignore. So here, while he did not actively work with Bradley or the Royal Society when the Gregorian Calendar was being introduced in England, and while that introduction was not an entirely horrible cr ime like certain things the R.S. did, Mason did still side with a party who was notorious in their purveyance of power over the less powerful and over those not even within their nation. In summary, with the introduction of the Gregorian Calendar, Mason may have known about the history of that act but did not realize the implications that such a thing held and likely did not realize that this type of action would be conducted time and time again to even greater, more evil, degrees. His journey to Cape Town and Saint Helena had revealed to him that foreign nations are still using their immense power to impose their own rules of law on these other nations. And thus, now being here after those trips, he should be finally aware.

When a patron of The George Bar asks Mason about his complicity in the calendar change, Mason assures him that he had nothing to do with it, though he would tell them all the story if they had enough time to listen. But as he begins, “A gleam more malicious than merry creeps into his eyes,” (192) signifying that, as with his story about Rebekah, he will not be telling the whole truth. And a malicious gleam signifies that unlike the other story, this is not to preserve the subject’s grace, but to maintain a facade. The story begins with George Parker, the Earl of Macclesfield, and James Bradley (who was already the Astronomer Royale by this time) walking near Greenwich Park. Macclesfield was his superior, being the President of the Royal Society from 1751-1763.2 As the two walk around, they discuss something known as the Great Chain, what we today would call a chain-of-command — the difference being that while a chain-of-command in our modern day typically refers to well-documented levels of authority, the Great Chain has more clandestine features regarding who may hold authority over who.3 Macclesfield rehashes the same rhetoric that Maskelyne did with Mason (1.13), telling James Bradley that while he and certain others may have more power than those like our Astronomer Royale, this so-called power comes at a price. This price is part ‘noblesse oblige’4 as well as the necessity of ‘lying.’ Or as Macclesfield puts it, “We who rule must tell great Lies, whilst ye lower down need only lie a little bit” (194). Maskelyne’s version to Mason had to do with ‘debt collections’ in that with less responsibility comes less likelihood that the power that was granted would ever be ‘collected’ on. So we see a Great Chain emerge, Mason being below Maskelyne, Maskelyne being below James Bradley, and now James Bradley below the Earl of Macclesfield. It is true that some of these debts exist, that the lies that must be told are there, and that some form of noblesse oblige is expected. However, one would have to be insane to believe that these qualifications make the possession of wealth and power more of a burden than not possessing it. Nonetheless, the never-ending reminder that these disadvantages and liabilities exist perpetuates the propagation down the line. If Macclesfield tells Bradley, then even if Bradley does not immediately believe it, once he starts using the same tactic to Maskelyne, he will fall into self-delusion. And then the same thing will happen as the Chain moves down: Maskelyne will not initially believe this, but once it gives him an advantage over someone else (in this case Mason), he will use it too. Mason thus aligns himself with these men in power, excusing their actions so that he will not have the blame placed on him. It is not that he condones their actions; but think of it as if Mason was a middle manager at a corporation like Boeing and Macclesfield was the CEO. No, Mason and some of the other managers may not fully condone the company’s actions, but in order to maintain their position, they have to excuse even the worst atrocities that those CEOs commit or else it will all fall back on them.

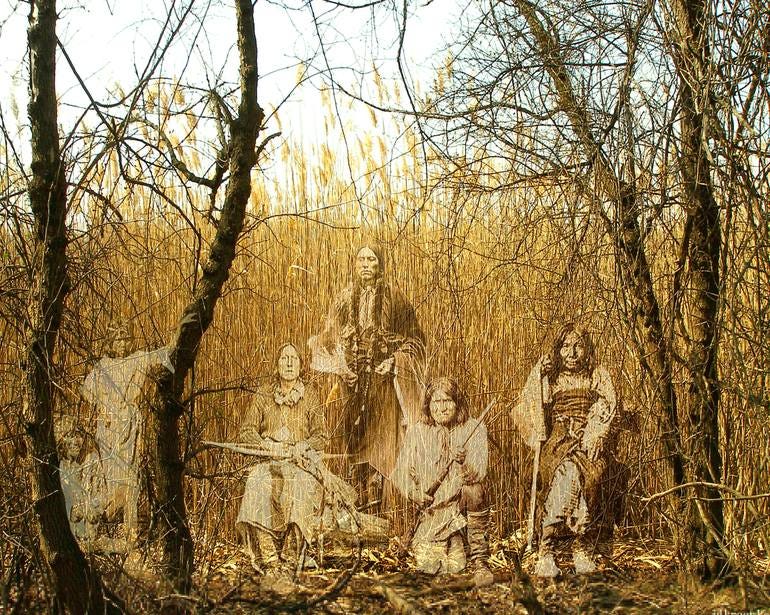

In this next section,5 however, while it is still Mason telling the story to the patrons based on how the novel is being told, we get a hint that this part is told by the Reverend Cherrycoke: “so the Revᵈ, who was there in but a representational sense, ghostly as an imperfect narrative to be told in futurity” (195). All parts told directly by the Reverend, especially those that are to some extent fabricated, have been allegories or warnings to the children he is telling the story to — and this one is no different. Remember that ghosts have been discussed previously and we have concluded that many within this novel remained on Earth for the reason that something was taken from them (1.7). These ghosts (or, as Mason calls them, pygmies) have had Time stolen from them. But since we know that no ‘time’ was technically lost, we can look at time as the same allegory we viewed above: an abstract concept imposed-on or taken-from a people. These ghosts that live within the eleven lost days will always live in the past, trailing behind the population who was affected by this change but who was not native to what was altered. In other words, while those who colonized certain lands are the ones who we will hear complaining the loudest as borders are shifted in America, they are not the ones who have truly had something stolen from them. They will not pass and become ghosts, awaiting to see whether their people are freed or not. Similarly, though more dishearteningly, those people ‘native’ to time will not see any of the so-called progress that the future brings, for they will be drawn back into the past, only ever living out a reality that should never have existed.

Or, perhaps it is the opposite. Are they the ones living in the true reality? A world that had never come but that should have been the future? The answer is unclear. All that we know about them, and all that they know about us is that “[they] haunted each other” (197). The ‘past’ and ‘present,’ reality and fantasy, are in communication. We see the ghosts asking for what is theirs, and they see us with a knowing look in our eyes, unwilling to give that thing back.

Similarly, Mason still sits in the bar, knowing now that the project he serves may have more evil intentions than he ever could have guessed. He has looked in Austra’s eyes, has witnessed the coming world on Saint Helena, and has seen how history will be rewritten in a museum upon that island. But still he sits here, excusing the actions of those who have stolen what was once these ‘natives.’ All while he thinks on how going back to his family now may not be so bad. He even looks forward to it.

Yet, that is the thing in itself. He has a family to go back to; he has a choice to go back to them or to stay here, buying pints for men so that they believe in what he says or at least like him despite their disbelief. But those native to so-called ‘time’ do not have that privilege any longer. It was stolen from them by the same men who Mason now defends.

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 20

To fix this, instead of just adding a day to the calendar every four years like the Julian Calendar did (a leap year), they crafted a system where every year that was divisible by four would be a leap year except years that were also divisible by 100 (i.e. 1800 or 1900) unless that year that was divisible by 100 also happened to be divisible by 400 (i.e. 2000 or 2400). All of these rules would balance the solar calendar so that on average the number of days per year would equal 365.2425.

It is now early in 1762 at the time Mason is telling this story, so his presidency is going to be over by the time Mason and Dixon are ready to set sail for America.

An example in Gravity’s Rainbow would be (in 3.30) during the discussion of the Freemasons and the Illuminati in regard to Lyle Bland. Whether or not these groups have legitimate power over elected officials is not something I am going to get into heavily, but there definitely are lesser known or unknown figures working within the shadows.

The supposed obligation that the wealthy and powerful must help the less privileged classes.

The analysis of this coming section took me quite a lot of time to develop. I had trouble coming to conclusions and there is literally no extensive writing that I could find on it elsewhere. I am relatively happy with the conclusion that I came to after hours of thinking through it, but I still do believe that this is one section of Pynchon that I either am not getting correct or at least am missing something major from. So, if you have other interpretations, please let me know in the comments.

What is the significance of Clothiers, and the defenestration thereof? They get mentioned often enough and in such seemingly unexpected contexts that I feel like there must be a meaning besides "someone who makes clothes" that I'm unaware of.

One of my favorite Pynchon relishes is when inherent and irreducible errors in measure carve out alternative timelines and geographies.