Gravity's Rainbow - Part 1 - Chapter 19: Death to Death-Transfigured

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 1 - Chapter 19: The Pöklers and Rathenau's Seance

We find ourselves back in the early 1930s when Peter Sachsa was still alive. It could be Eventyr’s unremembered discussion with Sachsa’s ghost, or the transcripts which were recorded of said conversations. But either way, back in time, Peter Sachsa’s lover, Leni Pökler, has left her husband, Franz. She has taken their daughter Ilse and now ponders on Franz’s “toy rockets to the moon” (154), Franz being a rocket scientist. Leni was, and at heart still is, a revolutionary, staying now with a group of women in a dormitory, actively working against the current Weimar Republic. Her and her fellow revolutionaries sit around discussing “the forms of capitalist expression” (155), all perversions focused on the idea of satisfaction, or a quick and easy solution. For, as they know, the maintenance of the capitalist system relies on brainwashing its constituents with mindless revelations, always teaching them to believe that a solution to their struggle is as easy as the conclusion of a shitty television program, or similar to the simple release after an erotic film.

Even as Leni is getting caught up in the revolutionary and feminist movements, her psychological state is highly focused on sex and love, noticing the sexuality of those around her in animalistic terms and pining over a man named Richard Hirsch — not a real person per se, but a onetime lover from childhood who is now a figment of her daydream, borne out of this desire for true love. All she had experienced before was the deadpan stare and impassion of Franz, the knowledge that he works for those dead set on killing us all, and she knows she deserves more. But the writing on the wall gives her an inkling that what she is striving for, or at least the method of which she is striving, is bound to fail: “AN ARMY OF LOVERS CAN BE BEATEN” (158), calling to mind Plato’s quote from The Symposium:

“If there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their loves, they would be the very best governors of their own city, abstaining from all dishonor, and emulating one another in honor; and when fighting at each other's side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world.”

Yet, the line Leni sees answers that by saying, not in this world. They have set things up a bit differently now, and falling for something like love leaves you vulnerable to more of their attacks. The ancient days are behind us now that They have taken over.

Before she left him, she and Franz often argued about Their attacks when Leni would want to go off to protest. He told her he was worried, knowing well that she could not be confident that those around her were not “working for the police” (158) or that she would be safe from any violence that may arise, for the forces at work were indiscriminate in their evil, and what would Ilse do if Leni got entangled in a resistance to the resistance? Though it seems cowardly, he is not wrong, necessarily. The ability to enact change in the world has become dangerous. It has been purposefully set up so that one must make a choice for a safe family life, or one where you can hope to ensure every family’s safety for the future. The latter could quite literally kill you. So, we end up with the disparity between those like Leni, who are willing to risk themselves for this prospect, and those like Franz, “the cause-and-effect man” (159).

Franz is haunted by childhood — his childhood and that of others (though, we will only see the others much later). As he walks alone one night, images and abstractions work their way into his mind. The sound of a waterfall in an ammunition dump forces a reflection on his own childhood: a trip with his mother and father where he held both of their hands. Whereas Leni’s mind maps abstractions of the world’s horrible inner workings over each other, Franz maps those of his past over those more awful ones. Perhaps this is where his profound paranoia and sadness come from — not a cowardice, though maybe a little of that, but from the fact that childhood seems to be something he needs to protect and maintain, and Ilse is that last vestige of hope. He cannot lose her.

What better to mar the reminiscence of childhood than the explosive failure of a rocket launch. As Franz walks into that ammunition dump picturing this childhood trip, he witnesses a group of shady individuals testing a rocket which subsequently explodes just above the stand. Terrified, he crouches until an old friend steps up to find him. This friend is Kurt Mondaugen,1 recently returned from a trip to South-West Africa (and we simultaneously learn that Franz was a one-time student of Laszlo Jamf, the same Pavlovian who had experimented on and conditioned young Tyrone Slothrop. All evil seems to stem from he who conditions us to act a certain way). After talking for some time at a bar, Franz returns home to enthusiastically relate to Leni what he had seen, a rocket test failure, but one that surpassed all previous tests in the possibilities that lie ahead. It was the V-2 rocket in its testing stage — the rocket that would barrel across the world, unheard, until well after it made its landing and destroyed whatever it happened to hit. This is how Franz, as we saw in the previous chapter, became an engineer in the German rocket industry, assisting in perfecting the V-2. Leni would have no part in this, and after some time waiting, hoping that some aspect of him would change, eventually left him and arrived at the dormitory where she now stays with Ilse.

Leni, seeing Ilse is starving, takes her to Peter Sachsa’s for food and happens upon a seance. Sachsa is attempting to get in touch with Walter Rathenau — a German politician and industrialist in the Weimar republic who was assassinated by a far-right group after being deemed a communist sympathizer. The group present with Sachsa had certain questions for him, though certain members had to remain outside as the seance went on. These members — the Preterite — gossiped about IG Farben’s latest scandal. A powerful weapon was designed and ready to be proposed which would “turn whole populations, inside a ten-kilometer radius, stone blind” (163). While this seems like something the war departments would love, remember: “Don’t forget the real business of the War is buying and selling” (1.14, pg. 105). It has much less to do with the death and destruction we see. In reality, it is what the market wants, and a powerful weapon like this new design could put IG Farben’s dye market out of business. The Military Industrial Complex must profit before anything else. Even before we win the war. The group further discusses “the Staffs at the Chemical Instrumentality for the Abnormal” (164), poisoning groups in Prague — a little call out by Pynchon accusing the CIA of conducting war crimes abroad.

Within the seance’s crowd sit the Elites who in this case are the corporate Nazis. While Sachsa is far from a Nazi (we know he is eventually killed by a police officer while he is in a left-wing demonstration), he is contracted by them to conduct this seance. He even tells Leni that he has no idea what the purpose is. The purpose is clear though: Rathenau may have been deemed a communist sympathizer, yet he was anything but. Walter Rathenau saw the coming WWII for all its possibilities in the post-war state. He realized that what could emerge from the destruction would far surpass political barriers, far surpass politics even. What would emerge would be a true hypercapitalist state where the Corporation would be deemed the Citizen and where Business would rule.

Rathenau begins to speak through Sachsa:

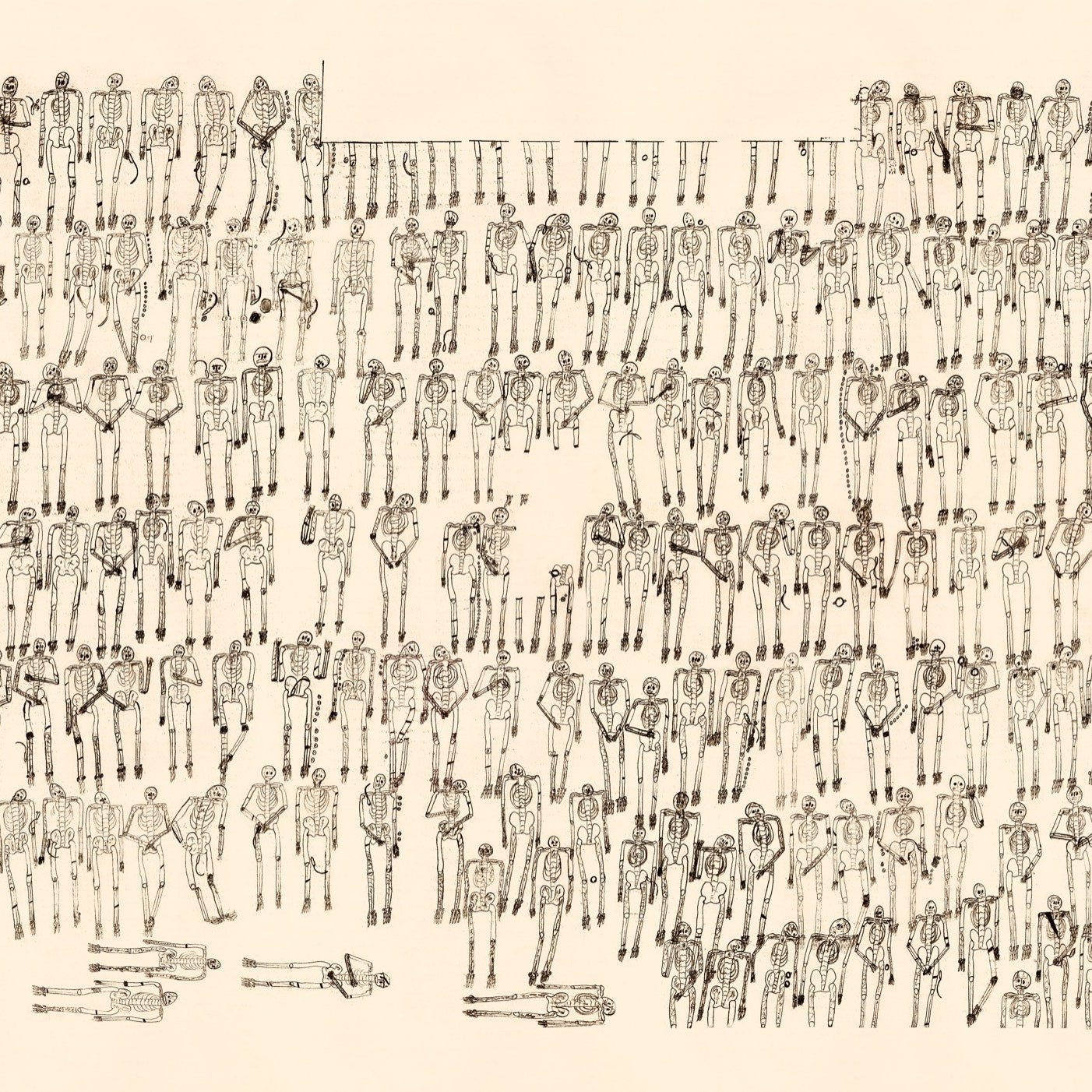

He speaks with a new understanding of the world now residing in the land of the dead. Knowing that “all you believe real is illusion” (165) and that no matter what he reveals to these Nazis, he knows they will adjust his meaning accordingly. But he goes on anyway, giving a sort of occult warning. He calls to mind coal, a substance that once had life: plants hundreds of millions of years old, broken down into decaying matter, pressurized, eventually become “the very substance of death” (166), a lifeless, dry, black thing. It is formed from species we have never and will never see, yet, like each person dying in the war, it will end up as that same piece of matter. Humanity has drawn out this coal, formed tars from its very essence, utilized those to craft shining steel. Of course, given the time steel came to life, “we thought of this as an industrial process” (166), humanity getting its bearings on what the Earth had to offer in order for us to build higher and better than ever before. We believe that we were creating life from death, yet “The real movement is not from death to any rebirth. It is from death to death-transfigured” (166). Where we thought humanity was evolving — learning to resurrect the dead to craft life — we were truly turning death into more death. New forms of death never seen. The coal tars would become steel; steel would become the rocket; oil would fuel the rocket. Death would be used to recreate itself.

The smokestacks, those polluting our air with the burnt up, dead corpses of coal, are themselves impervious and immortal. The molecules of death dictate that which we can create and repurpose. That which we can synthesize and control. But “what is the real nature of control?” (167). Of course, the Nazis only hear what they wish to hear. They do not see this as a symbolic condemnation of their entire plan, of the supposed birthright of the West, or of capitalism itself. They hear what will benefit them. They know what has been said, but the best they can do is giggle and ask, “Is God really Jewish?” (167).

Rathenau’s speech is a fantastic one, though in this instance I’ll have to give a lot of credit to Michael S. Judge from Death is Just Around the Corner for calling to mind its importance and giving me some background for my own analysis. My recommendation is to listen to his episode on this scene (or the episode that he guested on with True Anon) for a much better more coherent explanation (and I wish I could remember which episode that was, so if someone does remember, please comment below).

Overall, other than that incredibly important speech, this chapter served as an introduction to Leni and Franz Pökler, and though I analyzed it to some extent, it really should be read to better understand their characters and where they come from — the scared and intelligent man who will eventually realize his life’s mistakes, and the revolutionary woman filled with regret. They will eventually be used to reflect on the unfairness and hell of war.

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 20

A character in Pynchon’s V. who tells the story of when he was in South-West Africa during the Herero genocide with Lt. Weissmann (AKA Blicero). He also makes his way into Yoyodyne, a weapons manufacturer that plays a part in Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49.

Does Michael S Judge talk about this book in his podcast?