Mason & Dixon - Part 1 - Chapter 17: Inciting Events

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 1 - Chapter 17: The Jenkin's Ear Museum, the War of Jenkin's Ear, Paradise Lost, Back to England

Following the advice of Rebekah’s ghost, Mason arrives at Break-Neck, a valley “just a couple of miles southeast of Jamestown along the shore” (Biebel, 84).1 The closer they get to James’s Town, the less noticeable the wind becomes; the further Mason gets away from the bare bones of the coming Imperialist world and the closer he gets to those acute pleasurable distractions which he can now smell, the less he is able to feel that obvious coming.

Speaking of the loss and gain of various sensorial experiences, upon making it back to James’s Town, Mason finds his way into the Jenkin’s Ear Museum, a museum set up to house the Englishman Robert Jenkin’s actual ear, severed off the coast of Spain while he was at sea — an event which set about the War of Jenkin’s Ear.2 However, despite this war being started and named after the stated auriculectomy on the Rebecca, as we know from modern history, the inciting events listed in history books are rarely the true root cause of a war’s beginning.3 For example, while in school we learn that WWI’s beginning is because of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, we all know that this was just one minute and almost unimportant aspect in the grand scheme of things. Or, as will soon be mentioned, Helen of Troy being the only cause of the Trojan War seems to be a similar absurdity. Yes, these may have been the sparks that caused the explosion. However, the gasoline was spread, sometimes purposefully sometimes not, well before the match was lit. This ear — and the museum for it — serves a similar purpose. Because “this is but one Ear, yet in its Time, it sent navies into combat ‘round the Globe” (176). And anyone would have to admit that that seems just a bit simplistic.

But before we get to that, Mason must make his way down into the museum. He squeezes his way to the main room, hindered just a bit by the weight he put on indulging in the food at Cape Town,4 and coming out to the main room where he is greeted by the attendant to this museum: one Nick Mournival, the specter-like husband of Florinda who Mason and Dixon briefly met upon landing at Saint Helena (1.11). Apparently, Florinda has abandoned him for another man, probably giving Mason a little confidence since he believes that he and Florinda had a stronger connection back then anyway.

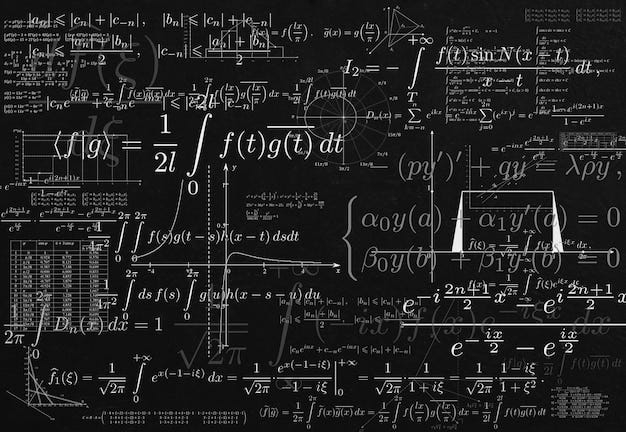

Mournival gives Mason a tour of the main showroom. To proponents of the coming world order, on an island such as Saint Helena, it is important to maintain the belief that war is started because there is a natural tendency for humanity to be at odds with one another, especially after acts of violence which come just as naturally. Many of the politics or the economic incentives should be as hidden away as possible so to placate the masses. Mason, and anyone who is being ‘educated’ on the Western Empire’s version of history, would be “awash in monologue and vocal Tricks” (177). Anything and everything will be done to ensure the listener or learner obtains the ‘facts’ but remains uncritical of the validity. Any sort of trick or rambling would be taken to ensure this. While these ‘monologues and vocal tricks’ are being placed upon him, Mason looks through something known as a Chronoscope which gives him the image of the Rebecca, Jenkin’s ship, as well as presenting some of the history of this so-called inciting event. But as stated, while this historical turning point was reported on in a museum, “the Event [has] not yet ‘reduc’d to certainty” (176). Instead, it is “wind express’d as its integral” (177). The wind, as known from Sandy Bay (1.15 & 1.16), represents the onward trajectory of history, specifically of a history moving toward Imperialism and Fascism. This historical path (also known as ‘the wind’), can only be understood in ‘integrals’ — integrals being, in calculus, “used to find the area underneath a curve by dividing that area into smaller pieces and then summing them” (Biebel, 86). In the same way, Saint Helena’s wind and thus the actual path of history (not the path stated in a history book or a museum) must be taken apart piece by piece. A single event like the removal of Jenkin’s ear or the assassination of an archduke is one slice of the ‘curve’ of history. What goes ignored or unseen are those other slices, namely the arguments over colony borders along with various trade disputes that were held between the two nations.

Britain, before the war, essentially gave the Spanish the ability to board and search their ships to curb smuggling; however, in time, this led to the Spanish abusing the privilege, eventually leading to the severing of the ear of one ship’s Captain: Robert Jenkin. On top of this, while the British had colonized Georgia and the Spanish had colonized Florida, the boundary dispute was contentious.5 So, as with Helen of Troy, the ear may have been the match, but the fuel had been laid long before. As with all wars, the root cause is greed for land, the resources of that land, and wealth in general. In the 1700s, these disputes were far less visible without media or instant communication but were also easier to comprehend if these events were to be somehow discovered. In our modern world, with easier access to information, inciting events and surrounding events need to be more complex and obscured. For example, while 9/11 or October 7th, 2023, were said to be the inciting events of specific wars and genocides, the desires and histories of the nations at war have far more to do with, again, resources, land, wealth, and nationalism than any one moment. Those surrounding events and history, however, are the harder-to-perceive integrals on the side of a curve whereas the inciting event is the one standing tall and apparent for all to see.

The final room of the museum is where we can see the preserved ear itself — the literal symbol of that war’s beginning. The ear has become an object of worship: an idol. Mason sees it for all of its lustful properties and is told, by Mournival, to speak to it, read to it from the Bible,6 and tell it secrets. In our modern times, we are told to trust in what we are taught regarding history as if it is the word of God: that the nuclear bomb was dropped solely to prevent our troops from having to land on mainland Japan, that the attack on Pearl Harbor was the only reason we decided to join the war, that the Cold War was ‘cold’ at all, that America’s instillation of ‘democracies’ around the world was to better nations that didn’t have the privileges we do, that certain attacks were done unprovoked and were not retaliations for decades of egregious atrocities.

Mason appears to see past this odd form of worship and uncritical trust. He views the ear as one integral section beneath the entire curve of history, understanding that to comprehend the real implications of what occurred or why, he would have to develop an immense body of knowledge similar to what a mathematician would need to do to further perfect their knowledge of that curve. Mournival continues to ask for Mason’s obeisance and trust in the Ear, which “has now definitely risen up out of its Pickle” (179). The absurdity and hilarity of this scene directly mimics the absurdity and hilarity of our own worship for apparently factual history. History rises up, erect, almost asking us to have faith. So, when Mason is finally forced to whisper something to the Ear, he initially wants Rebekah to live but realizes that Rebekah’s Ghost has taught him enough about history and how to perceive our world so to not wish for something as selfish as bringing back the dead. He instead focuses on saving the living, wishing Dixon would return back home safely.7 Afterward, scared of Mournival’s insanity, he runs off —

— and exits into what looks to be the Garden of Eden: what the world should have been with “Bright green Vines with red trumpet-shap’d Flowers” (180). Instead, however, it is not Eden. It is Eden after the Fall. As we close out our stay at Saint Helena, we learn that is exactly what this all was: “The St. Helena of old had been as a Paradise,” (1.11, pg. 105) but was paradise no more. Our world has similarly always been filled with bloodshed, but it was never as senseless and for such purely antihuman purposes as it is now. Paradise has fallen and we are left with its remnants — a world in which mankind can build whatever selfish and evil systems it desires.8

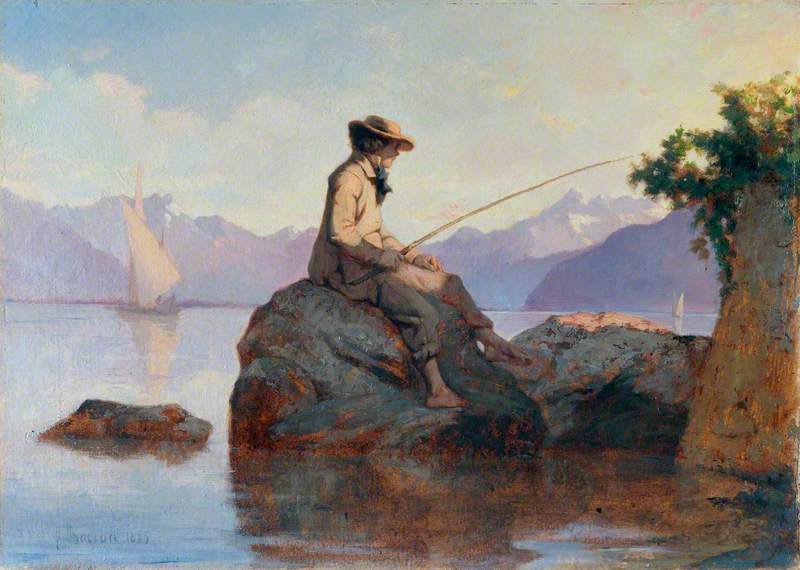

Time skips past when Dixon returns, past when Mason told him about meeting Rebekah at the Cheese-Rolling Festival (1.16), and onto when the two were now aboard another ship finally heading back to England where Mason told Dixon the entire story of what occurred upon the island while he was back at Cape Town. Dixon even states that he believes he heard Mason’s wish for his safe return while at The World’s End (1.14). And the two even discuss, for the first time, both of their love of fishing, something they hope, one day when all things settle, to do together.

The penultimate conversation turns to Maskelyne, who remained upon Saint Helena for apparently unknown reasons. Dixon proposes, like Ethelmer inferred before (1.11), that he remained for the easily accessible and consequenceless pleasures such as sex and booze. Mason, while likely agreeing to some extent, given he had seen Maskelyne’s gluttony and insanity firsthand, also brings up the fact that despite failing in observing the Transit of Venus, in finding the Parallax of Sirius, and so on, he now has the ability to further the science of calculating longitude using the Lunar Distance model, and so may be staying for that reason.

All this talk of Maskelyne is to avoid conversation of their future. Specifically, about something that Maskelyne has heard rumor of and that Mason now, finally, brings up to Dixon. The Royal Society is looking for astronomers to soon map an East-West border for a boundary dispute between Pennsylvania and Maryland. The two don’t believe — likely because of their disfavor with the Society due to their Letter of Reproach (1.5) — that they would be asked to do this, nor do they believe Maskelyne has any interest in such a job. However, given we know the name of this border in our period of history, we also know exactly who will be given this task. And with our recent discussion of history’s writing, learning that a boundary dispute between Georgia and Florida was one of the more hidden inciting events of a war, this next dispute very well could signify far grander implications than just a mere argument between landowners.

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 18

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.

This war actually did occur (historically) between 1739-1748. All of the history surrounding this event discussed in the chapter is pretty much true except for the existence of the museum on Saint Helena (Biebel, 85).

Think of Morituri’s story (Gravity’s Rainbow, 3.16) and its discussion of the true but often unstated politically or hegemonically beneficial implications for the war’s true purpose.

Seems that Rebekah’s saving of him in the story he told (1.16) didn’t fully remove his gluttony.

Robert Pumphrey. “The War of Jenkins’ Ear.” Warfare History Network, 21 Sept. 2022, warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/the-war-of-jenkins-ear/.

Mournival also mentions that he reads The Ghastly Fop to the ear, which is the title of a publication that you should remember for a large section in Mason & Dixon that occurs much later in Part 2.

Remember that even though we flashed forward in time in 1.15 and 1.16 to where Dixon was back, we flashed back in time after that to where Mason was still with Maskelyne at Sandy Bay, to Mason’s ride back to James’s Town, to now at the museum. So, Dixon is still not back.

This should also call to mind the Zone in Gravity’s Rainbow, being a blank slate for corporations and Military Industry to rebuild.

Aside that your use of images is stellar. I've been confronted with an odd issue releasing digests of my "Pynchon dailies" made in anticipation of Shadow Ticket, where when I don't have a specific image attached to a post, I am looking through Substack's stock picture app connected to Unsplash, and whereas any individual image I find works fine, the sum of them calls attention to their stock-ness, the weird detached authorship lacking personality vibe that ultimately makes stock libraries so frustrating.

On war: the moment in Against the Day when a couple of characters find an oil pipe in development and immediately realize that they won't be able to prevent the "general European war" they feel coming haunts me. I think that's another aspect of Pynchon's deftness with marginalia history: "Don't look at the event, that keeps your eyes looking only at what they want you to see. Look around at the stuff happening elsewhere to the event, there you'll see the activities causing the event."