Gravity's Rainbow - Part 1 - Chapter 14.1: Hansel and Gretel

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 1, Chapter 14.1: Katje and Blicero

The Present: Katje

Katje’s freedom has never existed. There has been the illusion that she was, or is, free — that she can travel and leave whenever she desires — yet this mist will disperse over time. She has arrived here, at Pirate’s flat, from somewhere far away, now followed by an unseen camera held by an unnamed man, each step and gaze tracked as she, feeling like she has the jump on him, watches Osbie Feel in Pirate and Co.’s flat. Osbie has harvested his crop from the roof — not Pirate’s bananas, but the poisonous mushrooms that he grows alongside them. As he concentrates their potency, and uses their chemistry to produce a psychedelic effect, it calls to mind the coming age — intelligence officers creating psychedelic drugs, hippies losing their conscience in search of that perfect high. That perfect hallucination. We are seeing the outcome before the outcome ever occurred, seeing its roots mapped over the past. Though, for now, as Osbie opens up that oven to process the mushroom, it shakes Katje as she realizes that for her, the oven will never close, and that “she is corruption and ashes, she belongs in a way none of them can guess cruelly to the Oven . . . to Der Kinderofen” (94).

The Past: Katje

“She recalls” (94). We move back in time to see her before her escape. Before she stood, watching Osbie, unknowingly filmed. And the first thing she remembers are his teeth. The teeth of Captain Blicero (Chapter 5 brought him up as Dominus Blicero, calling to mind a sort of God of death who is now equated with yellow teeth) are all that we can see of the human skull before death. Blicero is death peeking out of life — the absolute desire for the gums and mucosal tissues to peel back, for skin to follow, shedding itself to dry and crumble on the ground, leaving behind not only him, but the rest of the world, unmoving.

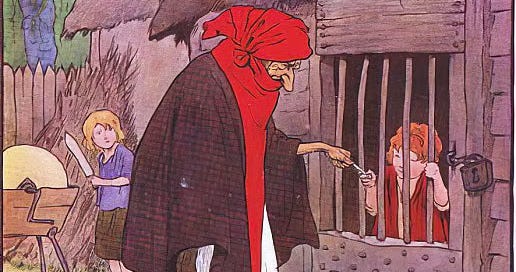

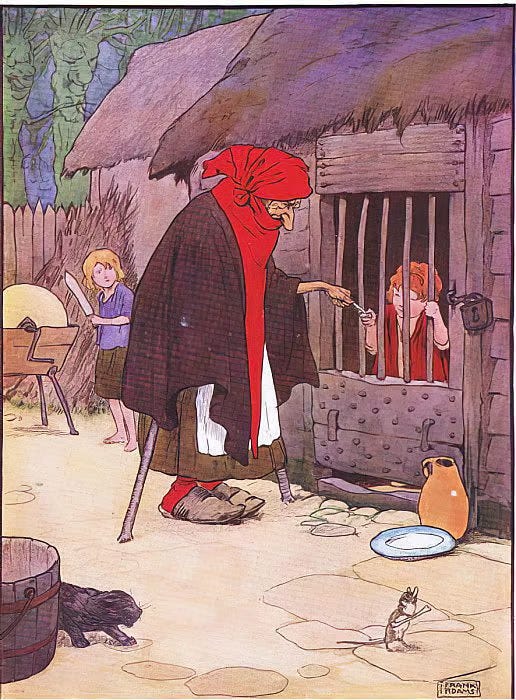

There is another enslaved with her — a boy, Gottfried. They are both there willingly, if you were to ask them, at least. They serve as submissive sexual objects for Blicero’s indiscriminate use, and that of anyone he wished to have them as well. Blicero plays not only the dominator, but the dominatrix, standing in drag as Katje and Gottfried kneel before him. His costume and “mock labia and bright purple clitoris” (95) are of course made of synthetic rubbers, in this case, a substance known as Mipolam. She and Gottfried are metaphorical siblings — Hansel and Gretel kneeling before the fire of the oven, subdued and abused yet, in this story, there is only one who seeks escape. Blicero takes away their identities — they switch between male and female, between Gottfried and Katje, they wear hair longer or shorter than their own, perhaps even grow and cut their hair, wear each other’s uniforms — and confuses them, but always returns them to their place: the “maidservant, and […] fattening goose” (96). And Katje knows that the goose is destined for the oven. Blicero, their captor, can be pushed into the fire, but the caged one must desire to be saved. Blicero, like Pointsman, has perfected his methods of control. He has led one of them to accept — even prefer — their place below. Even though he is controlled and exploited, his situation is preferable to whatever worse world may be out there.

Blicero uses the concept of routine to provide them “shelter, against what outside none of them can bear — the War” (96). He has instilled a fear of the outside in order to exploit on the inside. If all that is presented to them is death and horror, then how could they not find solace in their routine — in the fact that their responsibilities are to none but him and that they can all be achieved within his cage. But it is never enough to fear only what is out there, for eventually, the outside will seem so far away that it is as if watching fictional events from a television screen. Your desensitization will let them fade away like background noise. So, the tragedy, the sound, must occasionally break your routine. Whether planned or not, “not far from the estate, [a rocket] fell back and exploded, killing 12 of the ground crew, breaking windows for hundreds of meters all around” (96) and while Katje likely feared for her safety, she saw Blicero tremble with pleasure.

The Past: Blicero

Blicero has his fears as well. He is not just death, but the party of genocide. He is the Nazi — both officer and scientist — as Slothrop is the American. And along with the inherency of evil (for his is evil personified as well) being this archetype leads to the realization that he is hunted. He fears Katje knowing she is immune to his grasp. She serves her role and nothing more. Where Gottfried may be the brainwashed man or child who loves his oppressor, who knows they are controlled but believes the cost is worth it, Katje plays her part but knows what else may be out there. “Her commitment is not emotional,” (97) it is endured until something can be done. She is the one whom the oppressor must fear — the expressionless face, the ghost you do not truly know, the one who knows the truth. Even with his fear, he cannot get rid of her. As evil, he is beholden to keeping the oppressed nearby, and there are too many suspicious faces to merit their immediate expulsion. Besides, his body requires those lusts to be fulfilled. He would wither away without them, pass on into nothing but unimportance, impotence, and inadequacy. His lusts would not be sated, so what purpose would his place above any longer serve.

In the past, decades ago, he was known by another name; it was before he became The Witch — the Nazi. For before the transformation into pure evil, there is always the person. He once had a friend whom he lived in awe of, was once athletic and lived as any child in Europe may have. Blicero ponders where things may have changed: where the turn in his life came from, that obsession and desire to obtain and master the realm of death. The novel passes back into Sudwest Africa during the Herero Genocide. Blicero was a German at the time of the invasion, a captain.1

Here, Blicero fell in love with a young Herero boy. They fucked under the name of God much to Blicero’s paranoia of blasphemy. To Blicero, at the time, God was God — a creator and omniscient being to be praised and served. But to the boy, to the Herero’s, and to many cultures who had not yet fallen into pure monotheistic worship, God, or the Gods, were everything. The served as metaphors for life, opposites, glimpses into expressions or feelings that had no name. Blicero could not comprehend him, and it drove — is still driving — him mad. He named the boy Enzian, meaning gentian, picturing Rilke’s blue hillside. But Enzian states, “Look at me. I’m red, and brown . . . black” (101). His love has warped Enzian for he sees him not as the Herero, he sees him as its opposite, its negative, there across the seas on the other side of the world. He sees Enzian not as a person, but a point of light that the line of a poem sparks in the mind. Enzian’s God(s) is Blicero’s poem — their metaphors achieved through different means.

But, seemingly out of nowhere came “her sudden withdrawal from the game” (102) — Katje’s escape. She cannot save Gottfried, she cannot (at least cannot yet) push Blicero into the Oven. But perhaps, in the present, as she watches Osbie Feel inhale that hallucinogenic smoke, she can have a change of heart . . . and may even have a chance.

We got about halfway through this chapter this week, ending on page 102. Next week we will be continuing with Gottfried’s point of view.

This entire chapter, at least until a wonderful little anecdote near the end, is basically Pynchon’s version of character introductions. Katje, Blicero, and Gottfried (who we will be delving a bit more into next week) are major parts of this novel, and even though the analysis in this chapter is mostly just explaining how characters exhibit control or submission, they are the archetypes of those facets, so it’s still important to go over. But what I will say, the analysis is less important in this part than the language itself. Go back and savor those sentences, for how they’re written really gives you insight into who these characters are more than anything I could say would.

Up Next: Part 2/2 of Chapter 14

See Thomas Pynchon’s V. (1963) for a more lengthy and in-depth exploration of what happened during this genocide. Blicero was even in this chapter, though under a different name which we will discover later.

I don't know if this is the first time, but I noted that here is one place where Pynchon narrates through cinema: "The cameraman is pleased at the unexpected effect of so much flowing crepe..."; that's always been a technique in this book that fascinated me, and of course the significance of the reader as viewer is affirmed in the very last scene of the book...

Along with all of the rest of us preterite, I've only become aware recently of how pedophilia and sexual abuse are a key component of power out here in the real world. The oven game reads very differently today than it did before Epstein ... Pynchon knew, ofc.

"Special Attraction for Adults:

How Money Reproduces

Anatomically Valid

Not Just Entertainment

Money's Own Genitals

Nothing Left Out!"

-- Rilke, tenth elegy, Blicero's favorite