Mason & Dixon - Part 1 - Chapter 14: Hell Painted White

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 1 - Chapter 14: Dixon Attacked, The World's End, the Black Hole of Calcutta, the Great Trek, Children of the End of the World, Musings on Clocks, Surveillance

No longer with Maskelyne, Mason stands atop a ridge thinking of Dixon. The two have not been together for long and have been briefly apart for an even shorter period, yet still Mason feels like he has lost a part of himself. When the story gets just a bit too precise, one of the twins, Pitt, questions Cherrycoke, asking him how he could possibly know the exact contents of the letter that Mason wrote to Dixon if he did not even send it. If it was sent, that would be one thing, for it is possible that the letter still existed or was reported upon by someone else. But without even that, the letter was likely destroyed or never shown to a soul. Uncle Ives (Ethelmer’s father and J. Wade’s brother), congratulates the twins on figuring out the potential lie. He likely, like J. Wade, would want them to be skeptical about some of the stuff that Cherrycoke is ranting about — namely, questioning the hegemony of the age or bringing to light the existence of a shadow state. But also, even if Cherrycoke were being subtle enough so that the LeSpark adults did not pick up on these ideas, they likely would have picked up on his historiographic retelling of what really was going on. And one thing that these men would not want is for the youth to question the ‘official narrative’ which they have always been told. If the official narrative were discounted or even rendered to be as valid as any other narrative, then they might come to those more subtle ideas on their own.

Back to the story, told through Reverend Cherrycoke’s lens, shows Mason thinking on Dixon returning to Cape Town — a place that has more historical and material reason to exist than Saint Helena but that has suffered all the worse for it. And then, not only is it Cherrycoke telling the story, but Cherrycoke telling the story that Mason told him about Dixon far, far away. Dixon, who has now arrived back at Cape Town with the Shelton Clock, realizes that rumors have already been spreading after his and Mason’s departure. It does not seem true that Mason ended up acting upon his urges by sleeping with Johanna, but the people of the colony do not so readily believe in a man’s ability to withhold himself from sin, especially to someone who is willingly asking him for it.

The irony remains that Cornelius purposefully set up the old seduction plot, using Johanna and his own three daughters to get Mason to sleep with Austra. He willingly allowed the four of them to seduce Mason, sometimes even with physical touch. However, now that this seduction became common knowledge and now that the town gossips have sent out rumors like a game of telephone, everyone seemed to believe that the seduction’s purpose was pure adultery. Cornelius could not let this rumor affect the appearance of his masculinity, for he was the patriarch of not only the family, but the colony as well. Therefore, like many hypermasculinized men today, his only option (according to him that is) is to reassert his manhood and reclaim the woman which his people believe was ‘taken’ from him. He follows this supposed ‘Code of Honor,’ shooting at Dixon in retaliation. But when Dixon also retaliates, Cornelius screams, “No! I am supposed to do this!” (148) as if it should have been understood that in the code of manhood, the patriarch must ensure that he stakes his claim and takes revenge if what is his is taken. This obviously foreshadows much of the hypermasculinity of the modern day where men so often view women, or anything feminine, as something they can stake their claim on — something they must protect with unnecessary violence. However, this so-called protection does not have anything to do with actual protection but is instead a preservation of one’s manhood via holding onto one’s ‘property.’ And this, again, transfers into the realm of territory, where similar moments of unnecessary violence are acted upon when land is threatened or even said to have the potential to be threatened.

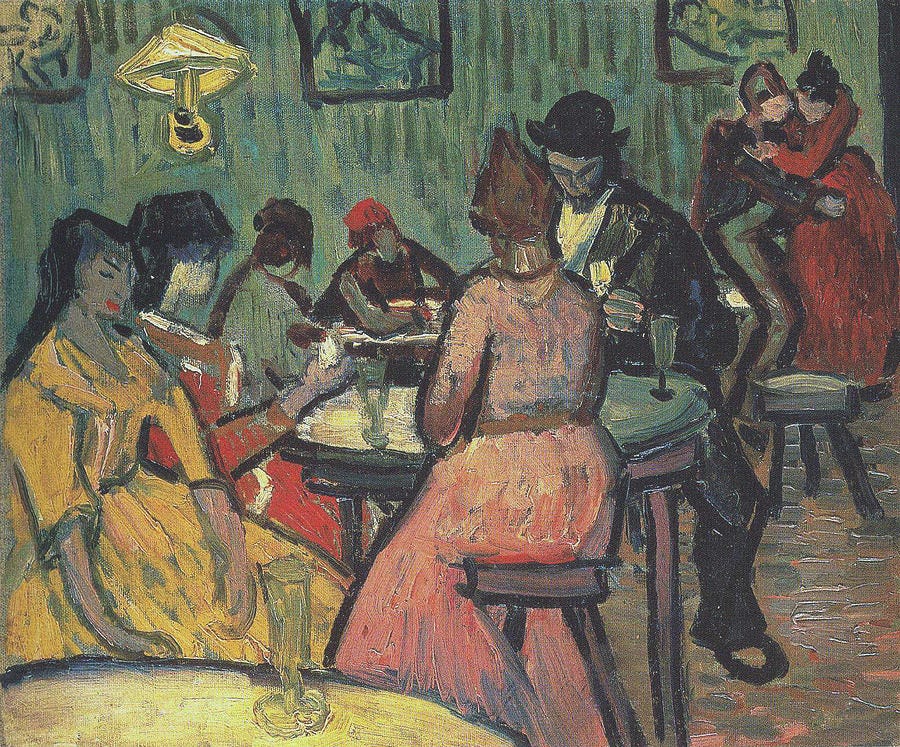

But when Dixon calls Cornelius out, he convinces him that his actions are genuinely insane given he’s not even Mason — the supposed perpetrator. So, the two of them retreated to Cornelius’ favorite Cape Town bar: The World’s End. This bar, appropriately named, is another foreshadowing of the coming global imperialist world. It is home to Filipino guitarists who spoke Spanish only because they had been colonized by Spain, home to Sumptuary Laws “designed to restrict consumption based on social class,” (Biebel, 76)1 home to slaves who have been so conditioned to accept their oppression that they do not feel comfortable going against these laws even if they were able, and home to goods from other lands such as “Opium, Hemp, and Cloves” (149). There too are many more comparisons to this coming world than are immediately seen. A fitting regular spot for the patriarch of this colony, but funnily enough, the patriarch does not even feel as confident as he is made out to be. And in such a place, Dixon does not feel as if he can “clear Mason’s Name of all Suspicion” (149). But luckily, Cornelius suggests that they seek other quarters to discuss.

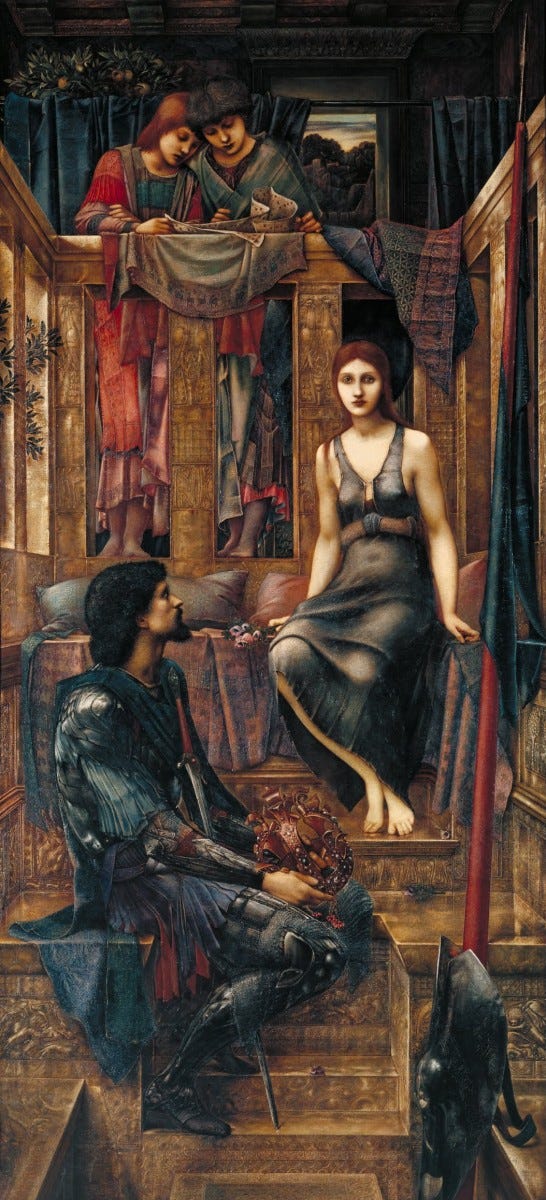

Those quarters, unfortunately, happen to be a brothel where “Austra, in a black velvet Gown and a leather collar, being leash-led by a tiny, expressionless Malay Sylph” (150) is brought by. Austra is not brought for Dixon or Cornelius, however. She simply is being dragged to another room to be forcefully prostituted out to whoever will pay the price. Pimped out more like since she will never even see a penny of the profits gained. And this is where we learn of Dixon’s unfortunate tendency of complacency. He cares but will do nothing to help. Austra notices immediately upon seeing him, through all of her pain and anger, that he will do nothing. He was here mere weeks ago feasting on the foodstuffs of the natives, wading his way through the prohibited districts, indulging in anything he could, all while returning back to the colonizers’ home to sleep comfortably. He is the modern man, making use of the pleasures that imperialism has brought about only to return to their domestic comforts after the fact, not giving thought to what has gone into these commodities. But here he sees what goes into them. He sees a woman — collared, broken, deadpan — and can only gape.

While Dixon gapes in horror and does nothing, at least he is not like Cornelius who doesn’t even not care but actively lusts after the exploitation of these people: “Let no one say that we cannot have fun” (150).

This brothel is covered in white, a veiled illusion of purity: “what light there is as White as Wig-Powder, flowing from pure white candles, burning smoothly in the still air, and from bowls of incense close by, white Smoke in the same unwavering Ascent” (150). Given that with Pynchon “white often equals death” (Biebel, 77) as a sort of subversion of the norms, white here is subverting the ‘purity’ of the environment and thus the ‘purity’ of the men in attendance. As we saw with Cornelius, many if not all of these men believe themselves to be the epitome of masculinity who are here to protect and provide to their wives, going so far as to defend their honor by any means necessary. Like those who believe in traditional ‘family values’ today, this is just as if one were to paint the walls of hell clean and white. For in reality, these white brothel rooms are hell, home to ‘Sloth’ and ‘Lust,’ where men can “escape from some Woman,” (151) even if that woman is who they had pledged their love and loyalty to. It is where men can indulge in several of the world’s deadly sins and purchase the bodies of others to use freely without the consent of the body being used, only because of the allowance of that body’s ‘master.’ Those family values and man’s supposed benevolence, loyalty, and love, in many cases are just hell painted white — an illusion meant to provide cover for the men in power, giving them the ability to indulge in their perverted fantasies and maintain their dominion all under the guise of ostensibly innocuous realms like ‘tradition’ and ‘family.’

As always, this specific social critique finds its way outward: “Many who have been to Rooms forbidden the others, report seeing, inside these, a Door to at least one Room further, which may not be opened” (151). The white painted rooms are hell, but they are only the first layer. Just as at the bar in Portsmouth where Mason and Dixon first met (1.3)2, the main rooms are open to anyone with at least some power, and the rooms further back are reserved for those who have proven their worth and who are likely willing to commit far more evil sins. And those deeper rooms possess doors that hold even worse things behind them. We see this same trend in the real world of sex work and sexual exploitation, where the strip clubs remain open to most, the brothels to even fewer, and then as wealth grows, more and more becomes available — high-end escorts, sex tourism to countries with fewer laws, the back doors of Hollywood, private islands owned by men with private jets. The brothel lobbies are one thing, but they seem innocent compared to what lies behind closed doors.

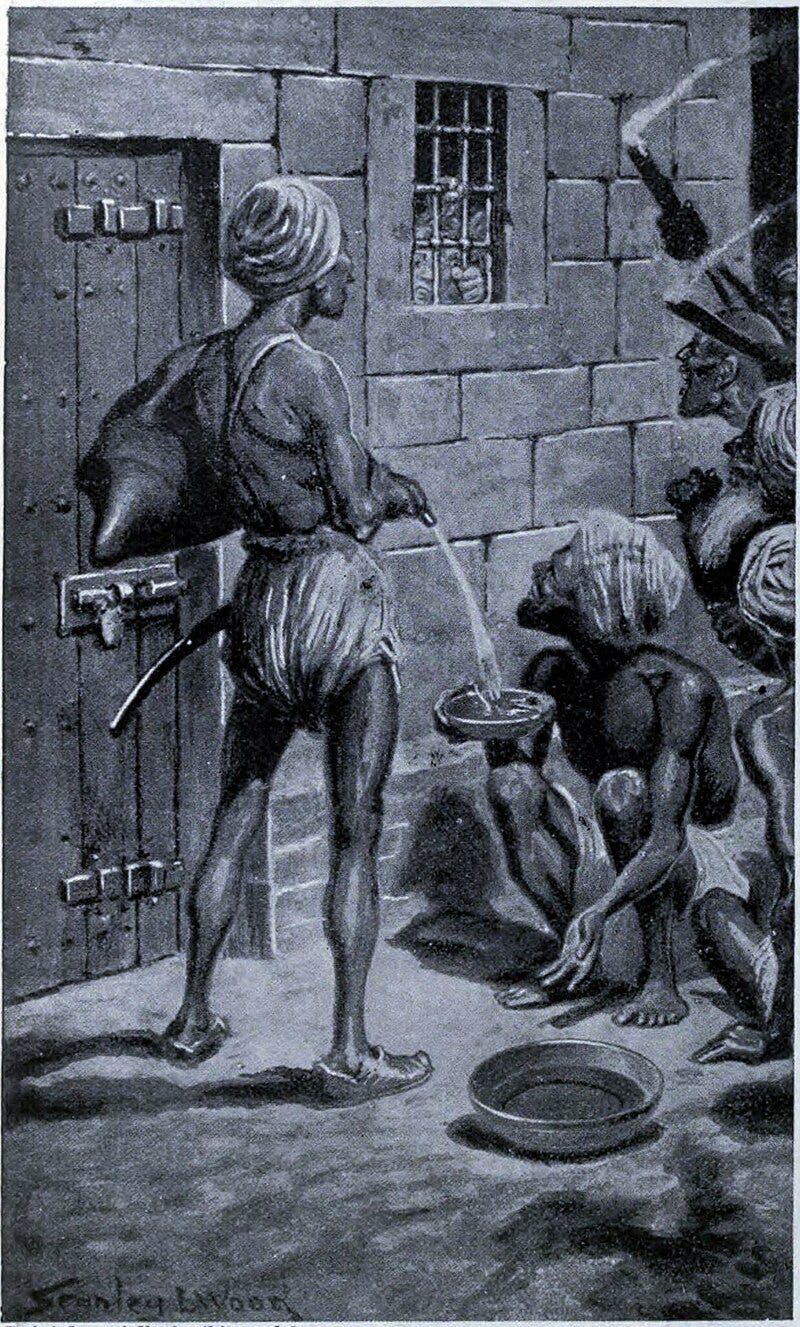

One of these rooms which we cannot see but can hear about by those who have, is a small-scale recreation of the Black Hole of Calcutta — a prison in Fort William, Calcutta (modern day Kolkata, India) in which a large number of British colonizers were crowded into a small cell leading many to die of dehydration. In this recreation, patrons of the room are able to experience an authentic moment of suffering — a fetishization of mass death. Given that the death of the colonizers came at the hands of an invading troop who were rivals to the natives that the British EIC were colonizing at the time, those who sought to relive this event also romanticized colonization as a beneficent force — one that may not always be pretty on the surface, but that was not the true evil deep down. Thus, those with enough power are not only able to recreate scenes of history which fetishize this type of death but can do so in order to reinforce the beliefs that all they had done in their colonization of the world was for the betterment of the human species as a whole. Cherrycoke critiques this view of the event in his Day-Book, stating that even this could not possibly justify any of the actions being taken: namely, encouraging “the teeming populations they rule to teem as much as they like, whilst taking their land for themselves, and then restricting the parts of it the People will be permitted to teem upon” (153). And when a British man (could it be J. Wade or someone of that ilk?) cries out, asking how the Reverend could be talking about the evils of the British when the British were the ones who were killed? the Reverend responds, stating how he sees that the death within the ‘Black Hole’ is nothing compared to the Indian lives taken by the ‘Company.’

And this all can still be seen today playing out again and again. We see acts of mass death such as the attack on 9/11 leading to an excuse for further acts of mass death that far outweigh the original. American’s sit and bask in the fact that such an act occurred on their soil, fetishizing it to an uncomfortable degree. But when those far more heinous acts being carried out abroad are called out, the Americans will accuse the accusers of being anti-American given the horrors that occurred on that ‘first day.’ Moments like these occur all over from small riots leading to absurd police brutality, a single retaliation leading to the genocide in Palestine, Pearl Harbor eventually leading to the dropping of the atomic bomb, and so on. All this while the ‘Company,’ the EIC, or more modernly the Military Industrial Complex, rakes in the profits no matter who dies or in what number.

When Cornelius goes off to indulge in one of his copious perversions, Dixon tries to escape. In many ways, Dixon is just like us, fantasizing about saving Austra (or in our case, one of the subjugated members or groups of society), but having no idea how to go about it or what one would actually do if they were to succeed. In reality, these excuses about uncertainty exist due to Dixon or us being too afraid to lose the basest creature comforts that we are afforded by those doing the exploiting. It is no surprise then that Dixon ends up at a tap room.

In this tap room is none other than Bonk, the VOC officer who originally welcomed Mason and Dixon to Cape Town (1.7) and who told Mason to put in a good word for him to a ‘man behind the desk’ back in Britain (1.10). Bonk, a settler and colonizer who did not have the same level of power as those like the Vrooms or the rest of the ‘Company’ (the VOC), has apparently had enough. He and many other standard Dutch settlers ceased working for the VOC because they had become disenfranchised with the loss of freedom and excessive surveillance.3 Initially, this is a commendable choice. Historically, however, this so-called Trek will lead to something even more evil. Biebel states that a Trek (known historically as the Great Trek) did occur deeper into South Africa in 1836 which led to the violent attack of many native populations who had previously been uncontacted. This would then lead to the Great Trek becoming a “part of Dutch nationalist mythology, providing the foundation for South African apartheid” (Biebel, 78). Soon, the same thing would happen in America. Certain so-called rebels would begin their trek Westward, displacing and slaughtering Native Americans as they went, leading to a genocide and apartheid in these lands as well. However, the self-proclaimed grace of the modern Americans would lead us to believe that while all that was bad, it was simply a part of our past and our mythology, and with our ‘gifting’ to the Natives certain reservations, we had atoned for our sins. It is thus that America itself lives in a state of silent and uncontested apartheid.

Dixon returns back to the Vroom house with Cornelius — the latter having indulged in the sinful pleasures of the brothel while the former remained chaste. At home, Dixon sees Jet, Greet, and Els for the first time in a while. He realizes what drew Mason to them was their willingness to look past what was told to them by their parents and “to seek the Shadow, avoid the light, believe in what haunts these shores exactly to the Atom” (155); or in other words to readily observe the ‘shadows’ that really made up the colonized land in which they lived. Therefore, they provided Mason with some hope that the coming generations would not be so easily swayed by the lies spoken to them by the rich and powerful, or even if they were, they would at least be critical and willing to seek out answers and truths on their own. However, while one can be observant and critical of the world they were brought up in, this is often not enough. For, criticism is one thing, but a willingness to relinquish one’s comforts and class status, even if it meant that these ‘shadows’ would fade away, is an entirely different feat. Greet and her siblings are the “Daughters of the End of the World,” (155) and having recently seen the brothel and all it held within, it is hard to believe that simple realizations and critical thinking could tear down such a structure. So, even though someone may be critical of the rising tide of evil, most action is kept suppressed by keeping the critics comfortable, even if it’s just comfortable enough. It is just how Dixon did not save Austra for the same reasons.

Greet converses for a bit with Dixon. She tells him that the Dutch have recently been attempting to better calculate longitude through the use of clocks that could keep time at sea, the same thing which Maskelyne was attempting and somewhat succeeded in doing. However, given the Dutch are trying to discover and take credit for this advancement, Greet tells Dixon that he may want to keep the clocks he is using secret, or else the Dutch (who are already wary about him being back here) may feel there is also now a conflict of interest.

Musings on this clock turn into musings on whatever is going on down at ‘the Castle.’ Here, technology is quickly advancing, and clocks are gaining the ability to break time down into smaller and smaller fractions. With heightened technology comes heightened surveillance; each time that time itself is broken down further, the more readily those who work within the Castle will be able to track and surveil whoever is doing what and when they are doing it. No longer will actions be tracked by the position of the sun, not by the hour or even the minute. They will be tracked by the second, and in not too long, as Don DeLillo would say in Cosmopolis, “Yoctoseconds. One septillionth of a second” (DeLillo, 79).4 But luckily for Dixon, no matter how much technology may advance, human error still lies within the picture. For example, there was a brief mix up as the VOC mistakenly labeled Dixon as having connections far more dangerous than he actually did, though this mistake led the Dutch to keep their hands off of him — conflict of interest or not — at least for now.

If it is not clear, the world being created by these various East India Companies, these men in Castles, these Royal Societies, and so on, are versions of a dressed-up Hell. Oppression, death, slavery, rape, subjugation, wrongful imprisonment, loss of true freedom, surveillance, are all a new part of this world. But the walls have been painted white, the children of the End of the World are given all the comforts they could ever hope for so to ensure that while we may be able to peel back that paint and see the fire that lies behind it, we will glue it back up, sit down in our reclining chairs, and forget about it for another day.5

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 15

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.

And in Gravity’s Rainbow in the room with high-backed chairs at the Casino Herman Goering (Gravity’s Rainbow, 2.2).

The idea of surveillance will briefly come back up shortly in this chapter, so keep it in mind given it led to Bonk and people like him to ‘abandon the cause.’

DeLillo, Don. Cosmopolis. Scribner, 2003.

This footnote has been added post publication (June 18, 2025): Please see my short conversation with CFM in the comments. They asked some excellent questions on certain things that I did not touch too much on (a separate interpretation of Calcutta and Greet exposing herself to Dixon). I think some of those questions are vital to the story.

I'm trying to read through, the book by myself. And I am so disappointed that I finally overtook you. I'll be coming back every week though. They really did help when I was starting out to look for certain things, which the more I read of yours. The easier it became to notice the same things you did! Probably not that great, in a chapter about indoctrination.

What do you think, of the Calcutta hole also being about sexual gratification of the powerful falling just to rise again? That seems interesting to me, the differences between men who have it all, living the fall,- to feel better(appreciate) the magnitude of power distance? Also any thoughts about the fact Greet exposes her bosom? The intent behind it? Another plot?

I really did make a substack just to follow you. Thanks for the effort.