Mason & Dixon - Part 1 - Chapter 12: The Many Faces of Time

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 1 - Chapter 12: The Moon, Maskelyne's Birthday, the Clocks Discuss Time, Dixon Departs

In a bar on Saint Helena known as The Moon, Mason and Dixon sit with Maskelyne, the soon-to-be Astronomer Royale who was originally to be Mason’s partner during the Transit of Venus and who was later paired with Waddington due to a bit of nepotism (1.7). Though, ironically enough, Mason and Dixon were the only pairing of the two groups who actually somewhat succeeded in attaining the information that was needed from the transit. Even more ironically, this does not really matter all too much since Maskelyne will be receiving far higher adoration for other reasons in the near future.

The group at The Moon discusses Maskelyne’s time spent working at Pembroke College, one of the oldest colleges at the University of Cambridge. It quickly becomes clear that Maskelyne, being so long at Saint Helena, is not exactly in the right state of mind. He has an immense self-consciousness regarding his one-time servitude of attendees at Pembroke College, especially since Dixon, despite being of a much lower class than Maskelyne, is now is familiar with the people whom Maskelyne once served. Along with this, Dixon insinuates that he believes many of the people who attend these colleges and universities end up going slightly insane whether it be due to excessive work, an overabundance of knowledge about the universe, or even whatever societies, secret or otherwise, the attendees were likely to join while at such a prestigious University — one that would be of the ‘Ivy League’ class if it were back in America.

Mason interjects, stating that we cannot forget about London itself causing some of this insanity, it being the chaotic mess it was described as with the people dwelling so close and growing in anger and irritation; as Dixon said, “How can Yese dwell thah’ closely together, Day upon Day, without all growing Murderous?” (1.3, pg. 14). The two clearly see how someone such as Christopher Smart could have gone off the deep end, starting in a place that breeds insanity and then moving on toward a college which allows it to grow. Maskelyne, however, is doing anything he can to ignore this conversation, for he himself has been growing rather insane upon Saint Helena, another quite obvious breeder of insanity given its propensity to cater toward momentary pleasures as a distraction from reality not much different from our world of quick consumables such as fast fashion, addiction like cell phones, or even pornography. An overconsumption of anything that begins the dopamine train, throws that individual further down a hole of mental anguish than really anything can.

However, Maskelyne’s insanity has not taken away his sense of humor, for as a cake is wheeled out, he realizes that they know it is his twenty-ninth birthday and so proceeds to lament about what he views as his final year of true youth.1 While it is pretty clear that Maskelyne is putting on a show with this lamentation, he is similarly reinforcing everyone else’s beliefs in his teetering on the edge of sanity. And even further evidence comes when Mason realizes that the Plumb-line on Maskelyne and Waddington’s Shelton clock2 was faulty, meaning the data which they collected in reference to discovering the parallax of the constellation Sirius and the moon (another task they were attempting to accomplish at Saint Helena) would not be complete without comparison to elsewhere on Earth.3

With the Shelton clock’s miscalibration Dixon is tasked with taking it back to the Cape of Good Hope to ensure that any mistakes with its calibration were fixed so to render whatever readings Maskelyne and Waddington were able to get at least slightly more accurate. The clock’s purpose was to move past the lunar-distance method of determining longitude and instead using the clock for a more accurate measurement (especially now that clocks were becoming far more reliable at sea). It should be no surprise that the lowlier people (in the eyes of the higher-ups) have been tasked with rectifying the mistakes of those same higher-ups. Would Dixon receive any more compensation or acclaim due to this extra endeavor? Likely not. Would Mason, who must now wait upon Saint Helena for Dixon’s departure and return, receive anything at all for this inconvenience? Also likely not. But as always, the average folk will be expected to fix the mistakes of those above us not due to any contractual obligations or even for a reward, but merely because we have been trained to believe we must do so and because it would breed ill will against us if we were to not. Maskelyne has some other stuff upon Saint Helena which he is far more intent on completing, hoping, likely, to ensure his notoriety and thus his eventual elevation.

This is why “When inform’d that he must return to the Cape directly, Dixon remains strangely calm” (121). He realizes that the expectation exists, and he very well may even be so indoctrinated into the hegemonically based mindset that it genuinely does not faze him. Maskelyne even gives him his ‘thanks’ by saying, “I’ll be sure to pass the Word along to London” (121).

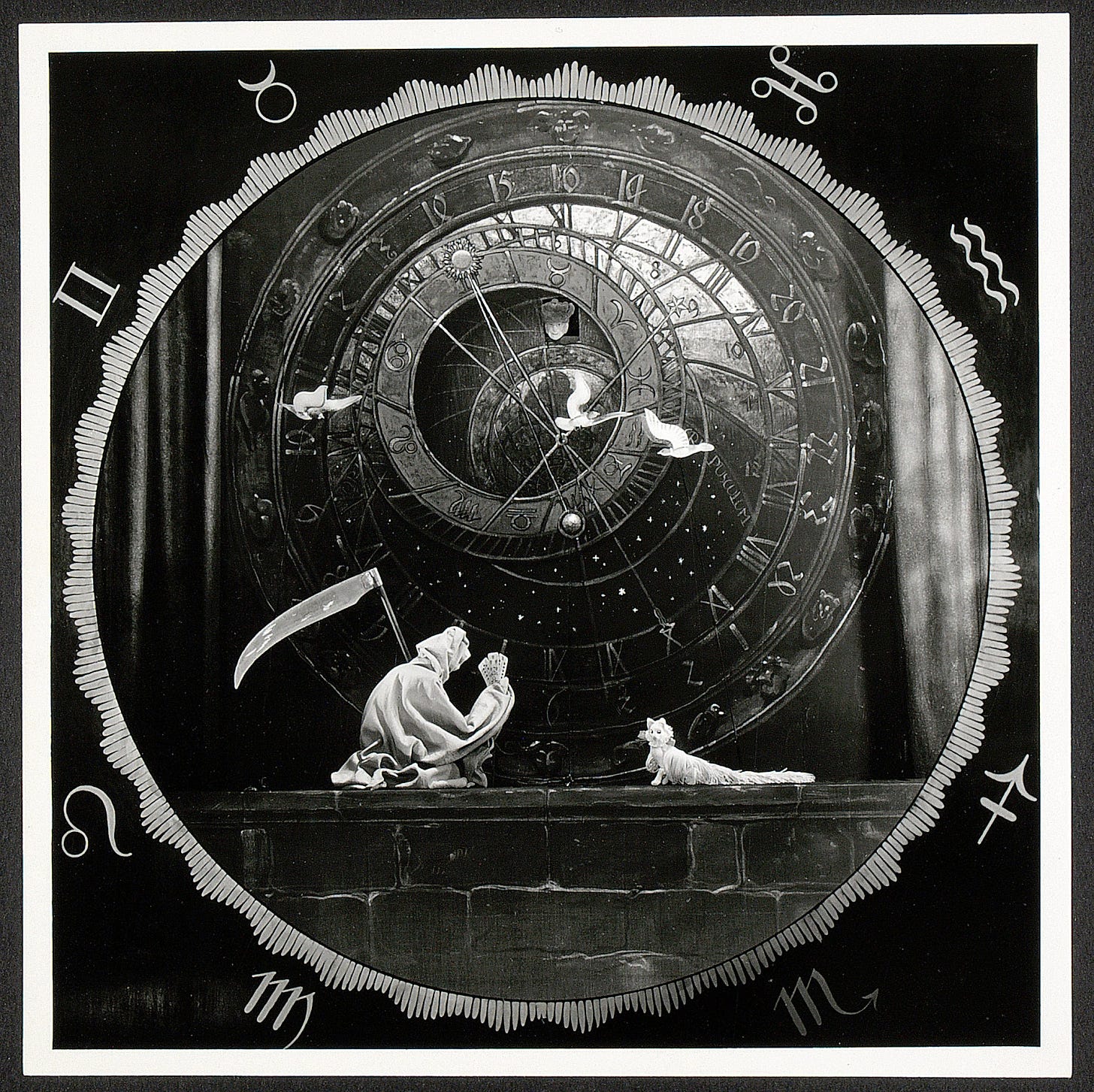

Before leaving though, and before much of this chapter’s events had actually occurred, Mason and Dixon’s Ellicott Clock4 stood alongside Maskelyne and Waddington’s Shelton clock upon a shelf. Because of the odd and mystical properties of Saint Helena and the ocean surrounding it, the two clocks are actually able to communicate for the short time they are together. As the clocks tick in tandem with the natural rhythm of the ocean, the conversation begins. Initially, the Shelton asks the Ellicott what things are like in Cape Town. This brings up a discussion regarding divisions of time. Time, in the modern sense, is — no matter how banal the saying — a construct. It is an abstract division of a day or a year splitting things up into fragments of our cycle around some solar body or upon the axis of the Earth: divisions of 12, of 7, of 24, of 60, of 365, of 52 . . . and even these aren’t perfect, furthering the proof of their abstract nature. For at times, those reoccuring divisions of 365 must be readjusted, those days in the second month of twelve must be reduced to account for ‘time’s’ imperfection. And we can even see how our Earth time varies completely from universal (in the sense of the actual Universe) time, given even the Transit of Venus comes at different times of the year, not bound by Earthly law. And this, inherently, is not a negative abstraction that we have created, for it gives us the ability to make better sense of our world and organize our days and years more effectively. Similarly, borders are not an inherently negative partitioning of land. But alas . . .

However, time (and borders) can be utilized in ways that make it (and them) a negative abstraction. For instance, our reminder of the passing day with a gong-like ring going off every hour is how we will partition off our workday, reminding us that we have only been here so many hours and reminding our employer than we have however many left. The Dutch take this to a whole new level, ringing this gong every fifteen minutes without warning, thus partitioning off the day into 96 distinct passing moments as opposed to 24 — a fourfold increase in the reminder of our servitude, the waning moments of our day, of our freedom, and of our life. Some, like Mason, may have a natural immunity to this reminder no matter the annoyance and discomfort it causes. Others, however, like Dixon, who had forgotten that time was passing, were instead “choosing, each time [they were] caught unawares to… well, scream” (122). Time therefore affects each individual in a wholly individual way, leading some to fear death, some to heighten their stress, some to bare down and get something done, and some to come to the realization that it is possible to commodify the entire concept of time. Maskelyne, for one, has lamented over the passing of his own years — twenty-nine cycles around the sun or ten-and-a-half-thousand rotations of Earth’s axis. It is not how he feels regarding his health, not that he knows what exact percentage of his life has passed, not that twenty-nine holds some truly horrifying possibility. It simply represents the end of a decade, a decade being another abstract concept whose passing we have been told to fear. All in all, the way in which we have divided time is no better than if we were to divide it by the rhythm of the ocean, for while that may not be a perfect science, neither is that of the stars. They all deviate at some point, whether over the short or long term, so what really is the difference? And again, the same goes with borders: whether it deviated a few degrees longitudinally in whichever way, nothing would really change. All of these are abstract creations which we have become accustomed to. They have been used for wholly evil purposes, but a reclamation of our world by the people who live in it would not necessitate the disposal of either of these concepts, for they both hold highly useful features. However, the fact remains that we cannot justify the continued exploitation and subjugation of a people based on these concepts. Because again, time and borders are abstract; people are not.

Before the two clocks can finally talk about the rhythm of the ocean, they are separated when Dixon takes leave with the Shelton clock to return to South Africa. On his way out, he and Mason say their goodbyes, calling each other by nicknames far more familiarly and friendly than they did not too long ago in England. Dixon says, “See thee at Christmastide Charlie,” (124) Christmastide being a year after their first meeting, signifying that our partitioning of days and time, of holidays and weeks, of whatever concepts that may very well be completely abstract, do in fact hold memories we should keep near to our hearts. Life, because of its absurdity, is filled with abstract concepts that have the potential to provide value, and yet those who control these concepts and the systems which rely on these concepts continue to commodify them or impose laws that only serve to separate us as people rather than bring us together.

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 13.1

Chapter 13 is another long one so it will be broken up into two parts. The first part will go from the beginning up until about halfway down page 134, ending with the line of dialogue that says, “‘Those of us with the Time for it,” suggests Mason” (134).

I write this as I’m quite literally also twenty-nine years old so this passage of Maskelyne’s lament (pp. 118-119), while always having been a funny one to read, is even better this time around.

A clock made by John Shelton specifically for the observation of the Transit of Venus.

Sections of this chapter and the last have always confused me regarding Maskelyne’s tasks upon Saint Helena. Namely, what he was doing with the Plumb-line and why it went wrong, what the Shelton Clock was used for, and his observation of the Transit, plus how they all tied together. Therefore, I emailed Brett Biebel who I’ve talked to before about this project and he cleared certain historical confusions up for me. So, for topics that involve the Plumb-line and the Clock, I attribute much of my historical understanding to him. This goes outside the scope of his book since it was through direct email.

A clock made by John Ellicott specifically for the observation of the Transit of Venus.

By the way, before I read the annotations, I thought Maskelyne was a made up character because of his absurdly Pynchonian name.

Another cogent and, if I may say so, almost prescient analysis.

I was particularly struck by your phrase, "But as always, the average folk will be expected to fix the mistakes of those above us not due to any contractual obligations or even for a reward, but merely because we have been trained to believe we must do so and because it would breed ill will against us if we were to not," which could almost serve as a commentary to my own career. Hopefully it doesn't reflect your own life experience as well.

Thank Glub I'm (mostly semi-) retired now.