Mason & Dixon - Part 1 - Chapter 10: Vectors of Desire

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 1 - Chapter 10: The Orrery, Vectors of Desire, the Transit of Venus, Fear of God, Return to Normalcy, Departing from the Cape, Tenebræ's Love, Euphrenia

From his Unpublished Sermons, Cherrycoke expounds on the connection between material and spiritual worlds. He elaborates on how our connection with nature is like our connection with God; independent of our comprehension of these entities (for example, how their laws work or what purpose they ultimately serve), our trajectory around them is the same. With the material, we follow Kepler’s laws in our orbit around the sun, and with the spiritual, we are tied (or are said to be tied) to God via the laws set out in the Bible and the teachings spoken by the prophets. Cherrycoke has therefore come to a conclusion that would potentially satisfy the astronomers’ (and particularly Mason’s) qualm in connecting the material and spiritual realms with his own worldview. But would it really satisfy them or him? It seems to say that these worlds are one in the same — that neither could truly exist without the other, or even that each one is a part of the same body of a singular entity. The issue (at least what Mason may say is the issue) is that this still provides no answers. If he were to ask the grander questions such as: is there truly life after death? are we meant to impose these invisible borders on the land? do the practices of these natives really connect them with the spirits? — then certainly just telling him, ‘well, it’s kind of just like Kepler’s law,’ would not entirely satisfy his desire for knowledge. Maybe that is the only answer that we can possibly get though — that it is just a part of the world we live in. Any further understanding must come through experience, or a deeper internal search.

Pitt and Pliny, new on this Earth (relatively, at least), show that their wonder at the material world is just as fascinating and confusing as that with the spiritual. They have an immense enthusiasm for the Orrery: a small-scale model of our solar system. To them, the mechanisms of this are just as fascinating and thought provoking as the possibility that realms beyond our perception (be they religious, ghostly, alien, or purely spiritual) could exist, and how they may function. In this way, it may be our constant exposure to the scientific phenomena that makes the material world so readily comprehensible and derivative, reducing our fascination with the fact that so much occurs before our very eyes which should invoke immense awe, but doesn’t anymore; it reduces it so much that it almost gives necessity to a belief in something beyond perception. Could it be an indoctrination with the separation between science and spirituality that renders us docile to something beyond mechanistic function? And even if mechanistic function (such as that of an Orrery) is what derives motion, why does that remove the possibility of something imperceptible?1 The children certainly don’t seem to see the difference, so when did we learn to separate these ideas?

While Ethelmer and Tenebræ continue their flirting — this time far more heavily — the twins tinker with the Orrery. It is revealed that a new planet, Uranus, was recently discovered, and the maker of these orreries traveled across America to make the addition. However, while making these additions, he designed the new planet in differing ways with each orrery similar to how history was being written at the time — the overall picture was kept the same, and yet minor embellishments were being added not necessarily out of ill intent or fabrication, but epiphany and artistic expression. And the three siblings loved this addition, creating new worlds and stories out of a simple added globe. They were taking history and crafting the implications of the new findings surrounding it. However, the difference in which they added these stories is quite telling, the boys using it to describe methods of war and Brae using it to derive “scientifick Inventions and Useful Craft” (95). She sees no point in continuing history as a series of combats and confrontations, or forgiving the fact that history is this. Instead, she wants history and discovery to continue as advances leading to the easing of humanity’s suffering.

And now, Cherrycoke explains parallax to the twins in the same way that Mason did to Jet, Greet, Els, and Austra in the previous chapter (1.9), furthering the theory that Cherrycoke is attempting to instill the view of history’s formation to the successors of America in hopes they can break the cycle. Joining them in this viewing of the Orrery is DePugh LeSpark, son of Ives, brother of Ethelmer, nephew of J. Wade, and Cousin of Brae, Pitt, and Pliny. He responds to Cherrycoke’s lesson with the phrase “A Vector of Desire,” (96) which is “an infant’s desire to reunite with the mother, and with the womb in particular [despite] […] this perfect (re)union [being] impossible” (Biebel, 53).2 This Vector is related to parallax in that parallax specifically shows the various potential paths that could have led to an end point. The Vector of Desire however seeks a ‘nostalgic’ path backward to the desired start point, or the path that has the most desirous trajectory of history. In other words, the Vector of Desire seeks a romanticized version of history that reinforces one’s own preconceived beliefs — a singularly biased path back through the moments that led us here.

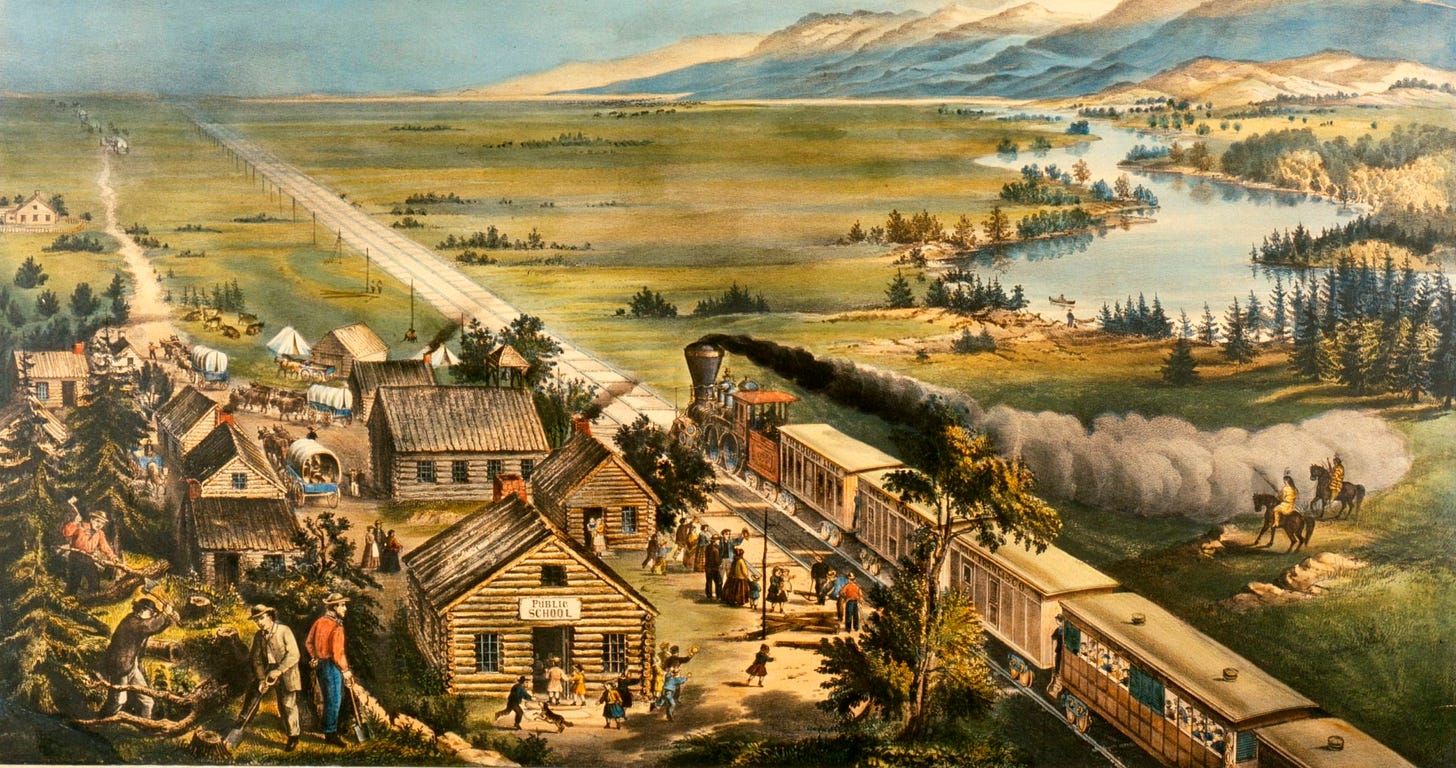

Mason and Dixon were last seen in the observatory with the three daughters and Austra, explaining parallax (1.9). Now we find them back here to observe the Transit itself — to experience their own singular ‘pathway’ of the event while others around the world view theirs. At the moment, Venus has touched the solar border and “A sort of long black Filament yet connects her to the Limb of the Sun” (96) just as in the fractional moment where a waterdrop merges with another and a thin ‘filament’ connects the two before they become one. This filament is, in other words, the Vector of Desire: a connection similar to an umbilical cord, but one which is now signifying the merging of two bodies rather than the separation of the two. Just as Biebel stated that the Vector was “an infant’s desire to reunite with the mother, and with the womb in particular [despite] […] this perfect (re)union [being] impossible” (Biebel, 53). Venus’ transit will only last so long, showing how that type of ‘reunion’ also cannot last, or symbolically showing how this sole vantage point merely provides the singularly nostalgic and romanticized view of history. Because history is not only being morphosed and altered from this single point by two men, even if those men’s names are the ones we will mostly remember. It is instead being altered and witnessed by those like the Military Band (1.6) who are speaking

in Latin, in Chinese, in Polish, in Silence,— upon Roof-Tops and Mountain Peaks, out of Bed-chamber windows, close together in the naked sunlight whilst the Wife minds the Beats of the Clock, […] Observers lie, they sit, they kneel,— and witness something in the Sky […] [.] [T]he moment of first contact produces a collective brain-pang, as if for something lost and already unclaimable.

(97)

This historical moment and path forward are viewed by every person, speaking every tongue, in every position, and in every situation. Some may have more effect than another and some may have very little effect at all, but each one of them has now been cut off from a certain possibility and has been sent in varied ways to a final event. History is derived from parallax. And not even just this one event can predict or give us the full picture. For we will need to see how things end up and change in eight more years when the next Transit can give us an even fuller picture.

Taking us back just a little, the clouds were heavy as the Transit was about to begin, setting everyone but the astronomers to worrying. Cornelius, despite never having shown much interest in anything that the scientists were doing here, even shows some fear that the clouds will remain, as well as showing an interest in what the transit will reveal. He is thus fearing that history will progress on a path that cannot be analyzed and observed, fearing that he will not be a part of what led us from point A to point B and will thus only be a rider on the train as opposed to a pointsman switching those tracks. We can thus see that men of this sort of power only really show interest in the workings of the world (be it science or spirit) if it serves to tighten their grip on the lever. And while during the transit, as we read earlier in the chapter, Mason and Dixon seemed quite levelheaded, it turns out here that they too were becoming a little bit antsy at the possibility that the clouds would render their journey pointless.

However, when it arrives, and when Venus’ ‘filament’ finally merges with the sun, when the child falls back into the mother’s womb, Mason and Dixon start recording the times. They realize that the culmination of scientific history has led to this moment — the history regarding Galileo’s discovery of heliocentrism and his use of the telescope, Newton’s laws of motion and of gravity, Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. All these discoveries and laws have coalesced to allow this new observation to occur, and it is occurring all around the world. Parallax even occurs in the near proximity as we see Mason and Dixon’s recorded times being slightly off from one another. And since it is obvious that they didn’t literally see a difference in when Venus touched or passed over the sun, it can be said that parallax does not just occur from varied points on Earth or varied perspectives, but from distraction or emotion. One of the two may have been distracted for a moment, forgetting to start their stopwatch, or even overcome with the emotion of the event and having done the same. Historical parallax occurs in a similar manner as this. We have already discussed how varied perspectives around the world from an immensely diverse human population can affect history’s reading. But here we see that people with the same goal in mind, in the same place, with the same heritage, speaking the same language, and who are even familiar with one another, can still produce parallax. A heightened emotion can render our reading of history different than someone who was purely stoic, or our inability to completely focus (be it purposefully or by accidental distraction) can do the same. Jet, Greet, and Els experience this event simultaneous to the Astronomers, producing another form of parallax. They are witnessing the exact same event from nearly the exact same location, but their breadth of knowledge (likely not including much Galileo, Newton, Kepler, or other scientists) is not nearly as extensive. One might as that if they literally observed the same thing, what renders their observation, interpretation, and memory any different than our Astronomers? This is a form of intellectual parallax where before we’ve had emotional, observational, locational, demographic, and so on. There are a near infinite number of ways in which this singular ‘turning point’ can be read.

And just like that, the Transit of Venus of 1761 has passed. Though, it will return in about eight years in 1769.

With the transit over, in the time between it and “when Capt. Harrold, of the Mercury, finds a lapse in the Weather workable enough to embark the Astronomers, and take them to St. Helena” (99) — their next destination before returning home — the Dutch simmer down. There are no antics to try to get Mason to sleep with Austra, the girls act almost as nuns, and the Vrooms “walk about for Days in deep Stupor, like Rakes and Doxies after some great Catastrophe of the Passions” (99). This event, though literally a thing that occurred in history, really is history itself — or a metaphor for a turning point in the story of mankind. Even the most powerful in the land, independent of whatever parallax they may have viewed it through, cannot bear its weight without showing that it has changed them. For a bit even, perhaps due to the scientific and spiritual worlds melding in the transit, making them recall a fear of God or an otherwise otherworldly revelation, the Dutch are “beginning to talk to their Slaves[.] Few, if any beatings” (100) have occurred since. It reminds Dixon about “when Wesley came to preach at Newcastle,” (100) instilling this fear of God in the people and teaching them that if they ‘sat quietly,’ ‘abided,’ and “tend[ed] to our various mortal Requirements,” (101) Christ would return and forgive those who were worthy. The Transit of Venus thus acts as this sort of religious fear in the same sense of contemporary religious epiphanies which can make someone improve themselves for a short while, but where their true self will always be ready to reemerge if they are tempted by the ‘Devil.’ Similar to that reemergence, things return to normal at the Cape, as well. History may have changed, but the people haven’t (at least in anything more than the acute sense). So, when a group of Company Writers from the EIC arrive, the girls and Austra resume just what they had been doing with Mason, realizing that Mason was not a target that would likely relent. On top of this, “Any fear that things might ever change is abated. Masters and Mistresses resume the abuse of their Slaves” (101). The fear of God has left.

With that, it is time to leave the Cape of Good Hope; they have gotten all they need. On their way out, Bonk (the man who welcomed the astronomers to the Cape — 1.7) reminds them that they will be reporting to some mysterious figure behind a desk once back in England, and that he hopes they will say good things about him. Mason does not believe they will be meeting any supposedly bureaucratic figure because he “again tries to differentiate the English from the Dutch, but Bonk knows better” (Biebel, 56). And so, they are off on the seas once again, this time to a small island we’ve heard about a couple times now as a waypoint back to their home.

At the LeSpark’s home again, the Reverend expounds on the differences in desire between the scientists and those paying the scientists. It turns out that there is not inherent good or evil in science just as there is no such thing in spirituality. While many may view science as the only means to view the world, some may view spirit as that only way, and some may have some combination of various balances, the thing that can produce good or evil out of these worldviews are the intentions for their use (or, in other words, Vectors of Desire). “The Astronomers’ own Desires” (102), for one, are rooted in science as both a curiosity and to further our understanding of the world. Mason too is using his spirituality and religion to find meaning beyond this. These are both obvious positives and goods within the two realms. However, we also see the “unshining Assembly of Human Needs […] including certainly the Royal Society’s need for the Solar Parallax” (102). This is a ‘rooting’ in science with far more evil intentions, using science as a means to perfect navigation, the development of borders and colonies, and as a control mechanism. Or, in spirit, this same society (or even societies far more hidden) will use spirituality and religion in theories such as Manifest Destiny to enact evils just as horrifying or even more so. Tenebræ, our glimmer of hope, realizes that what causes good in either of these realms (or in any realm for that matter) is something so simple that many may say it is a cliché or a platitude: love. And while it is a platitude, that doesn’t mean it isn’t true. It is overly optimistic, but it is only so because the world in which we and which they live in has done everything to subdue love that could possibly be done. Because love for another person, love for discovery, and love for some unseen spirit of the world all could lead to a desire to remove the systems that use those realms for evil.

While discussing Tenebræ’s love for discovery as she remembered herself once viewing Venus, Aunt Euphrenia walks in — sister of Revered Wicks Cherrycoke and Elizabeth LeSpark. She is quite a bit less timid and shrinking than Elizabeth, likely because she herself has not married a man who, while he may appear docile on the surface, given his job is anything but. Euphrenia gives Tenebræ a taste for what life for her could be like absent of the typical subjugation that a woman would face in that time when oppressed by a patriarch, which itself takes on allegorical means showing how a person could exist without a militarized imperialist state. Instead of suffering quietly, almost never to be seen like Elizabeth, Euphrenia pokes fun at the family, playing her oboe, and calling out certain Americans for pretending they are still apart of the old continent while only being able to satisfy their desire for that country via trade. And while Euphrenia too has desires for foreign commodities, it seems that she at least is willing to make those travels to foreign lands herself instead of relying (too heavily, that is) on global exploitation and commerce.

In all, the various Vectors of Desire are abound. Whether it be a desire to read history in the way that best suits you, to utilize science and religion for good or evil, or to remove oneself from a patriarchal structure to experience true happiness and freedom, each person and nation tethers themself to some hope for the future that has root in a nostalgia of the past.

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 11

I do want to take this moment to address my own point of view on materialism versus spiritualism so you are able to distinguish what might be my opinions and biases from what the text is saying. I try to keep my own biases out of this analysis, but it’s impossible to do so entirely.

I believe in the scientific world. I am not religious. However, I do believe that the ‘spiritual’ world exists in some sense, whether that be an imperceptible connection between man and nature, or man and the cosmos — it could be something ghostly, something alien, or something extradimensional. I simply cannot fathom the existence of the world only based on pure materialism. However, I also believe we should base politics and policy on materialism since that is what affects humanity on the most literal, observable, and verifiable level. That being said, a deeper connection with the ‘spiritual’ world would enhance many things that lead to a desire for material conditions to improve, so while I believe action should be taken purely from this material perspective, knowledge of our world should attempt to reach beyond. I also genuinely believe this is largely what Pynchon is trying to say in much of this novel. Could that be one of my biases? Definitely. But it’s hard for me to read it any other way.

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.