Mason & Dixon - Part 1 - Chapter 1: Writers of History

Analysis of Mason & Dixon, Part 1 - Chapter 1: The Home of the LeSpark's, Between-Times, the Family Introduced, the Story's Beginning

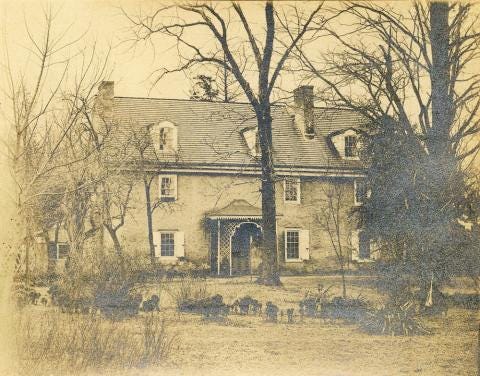

Our story begins during Christmastide of 1786 in the Philadelphia home of a wealthy couple: husband and arms dealer John Wade LeSpark and his wife Elizabeth LeSpark. It is a beautiful home, one which even 240 years previous to our contemporary era was able to build ‘outbuildings’ on their property, afford sleds with “Runners carefully dried and greased,” could refer to its kitchen as a great Kitchen, owned numerous types of pots and pans for various forms of cooking, and was even able to procure luxurious foodstuffs such as “Pie-Spices, peel’d Fruits, Suet, [and] heated Sugar” (5). Today, the children are having a snowball fight. The tidings seem lighthearted and gleeful, though specific uses of vocabulary hint at something ominous behind the more innocent tone. For instance, while they may just be snowballs, something having ‘flown its Arc’ calls cannon fire and artillery to mind, and the line “given over to their carefree assaults,” (5) especially given this was during the time of the horrific genocide of the Native population, calls to mind the nonchalant nature of continued assault on a people who have already been oppressed and killed for as long as the surviving members can remember. However, while the children are the apparent assailants in this situation, theirs is no complicit assault. They are the mere allegories of said oppression, and barely at that. For, they have been raised in this household — the home of the truly complicit. Their home is a representation of America, a land built on genocide and oppression which they have only had the misfortune (or the fortune, depending on how or where you look upon it) of being born into. Here, in this house, they have been subjected to objects as natural as Card Tables, which while they may appear innocent given it is what they were raised with, have actually caused “an illusion of Depth into which for years children have gaz’d as into the illustrated Pages of Books” (5).

1786 is an important year — or at least those years surrounding it are important. It is, like the dates in which a majority of Pynchon’s novels take place in, a between period1 of history — in this case, between the end of the Revolutionary War and the ratification of the Constitution, giving way to our first ‘glorious’ US president. (Similarly, while this time period in the home of the LeSpark’s is our frame story for the true story of Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, the main story of those two characters will take place within another ‘between period’: between the long centuries of America’s colonization and the beginning of the Revolutionary War). This, 1786, is the time period in which we will be observing the formation of America and the West. We will see how the characters who built it without knowing its intentions react; how certain mythologies or allegories will be used to represent it consciously or subconsciously; how power structures would bring about its creation; and how the implications of its creation could be tracked from their initial formation into their contemporary states.

In the year of the frame story, “wounds bodily and ghostly, great and small, go aching on, not ev’ry one commemorated,— nor, too often, even recounted” (6). Bodily wounds are what we can see and observe without much thought: a broken bone, a gunshot wound, a death. Ghostly wounds are something altogether different: mental tarnishing, spiritual death, religious faltering, the giving up of one’s humanity. It is not something you can altogether see without a complex observation of the surrounding provocations and implications. But with these observations (via the entirety of the coming novel), these wounds will emerge as something not only ‘ghostly,’ or even ‘bodily,’ but a wound wholly destructive to all we have ever known — a wound to the human condition, to society, to love, to family, to our people. Some of these ghostly wounds may even be seen in products that we consume every day and may not even think of as wounding. Coffee, for instance, “flows ev’ryplace, borne about thro’ Rooms front and back” (6). It is a substance which could not exist in the countries and states which it does without colonization and imperialism. South America, parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, all grow the coffee which is brewed today in America. We grow virtually no coffee in the US: only in Hawaii and Puerto Rico (which, if we can be honest, should not be territories of the US), and in parts of Florida. These substances of colonization lead to “Hammers and Saws [to] have fallen still” (6) — they allow us to relax, take a load off of our shoulders, sit down to have a drink of Madeira, all at the expense of a subjugated world of people who we will blessedly never have the misfortune to see.

We begin to meet members of the family, beginning with “the Twins and their Sister […] 'gather[ed] for another Tale from their far-travel’d Uncle, the Revd Wicks Cherrycoke who arriv’d here back in October for the funeral of Friend […] and has linger’d as a Guest in the Home of his sister Elizabeth, the Wife, for many years, of Mr. J. Wade LeSpark” (6). So, to start us off with our character list of those within the LeSpark household, we have the Patriarch, J. (John) Wade LeSpark, briefly mentioned above already. As was told at the beginning, and what will be discussed at further length later in the novel but is important to remember now, is that he was an arms salesman and achieved his wealth through this industry — a precursor to the military industrial complex. His wife is Elizabeth, who plays a more minor role in the thematic layering of the novel, which in itself is a thematic layer, also occasionally goes by ‘Zab.’ We will not learn much about her until later. J. Wade and Elizabeth have three children: the ‘Twins,’ Pitt and Pliny, and their older sister Tenebræ. Pitt, named after both Pitt the Elder and Pitt the Younger, and Pliny, named after both Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger, were named as such since “none could agree which had been born first,” (7) and thus they could both be referred to as Elder and Younger. They are the future American Patriarchs given they are the sons of our Military Industrial man, and they will be the main listeners of the story of Mason and Dixon soon to be told. Thus, what they are told will influence the leaders of the historical future — not in the sense of political leaders, but leaders in the realms of wealth and status. Tenebræ, the daughter of J. Wade and Elizabeth, older sister of Pitt and Pliny, is named after the religious service which represents the coming ‘shadow’ or ‘darkness’ after the death of Jesus. Since she is the daughter, thus not being the one who will fully inherit the wealth of the current Patriarch, and since much of her character’s exploration will be in regard to early feminism and comparisons between the power dynamics of her and other men listening to the story, the connotation of the ceremony in her name represents a coming darkness to the hope that exists for those like her — meaning both in the feminist sense and in the sense of those with less power or wealth. Finally, we meet Revd (Reverend) Wicks Cherrycoke. He has come to town to attend the funeral of a former friend (who we will learn of soon) and is allowed to stay for an extended period of time at the LeSpark home if he entertains the children with a story. His name, obviously signifying he is a Reverend, also signifies something ‘saccharine.’ Thus, we should interpret the story he tells as being, at least at times, overly-saccharine — or, to put it otherwise, glossing over some of the more nefarious instances of scenes, making America and the act of colonization seem a bit less brutal than it actually is. Of course, saccharine stories do not mean he is purposefully trying to whitewash our history (more on that later) but that he is, in some sense, glorifying it. His allowance to stay in this house can be interpreted as, ‘as long as you can make light of certain worldly events, thus teaching the future generations of a military industrial man how to think, you’ll be allowed to stay in America.’ As we’ll see, inklings of doubt to this ‘making light of events’ will seep into the story quite a bit, but very rarely will the story ever explicitly state it. (Of course, there are numerous versions of stories being told ranging from Cherrycoke to storybooks, likely to Pynchon himself, so some narrators or storytellers may be more liable to allow a slip than others).

Story time is about to start: Tenebræ, takes up her spot on the mantle, engaged in the Needlework that would have been expected for a young woman to engage in. The Twins, Pitt and Pliny, arrive with a basket of sweets — as if about to attend, in our modern day, a movie — as well as bringing coffee for the Reverend. They have been told numerous stories before, all by Cherrycoke. Yet now they ask for one about America. This electrifies the Reverend’s imagination, calling to mind numerous names, most of which, at this point, we’ll have never heard, but who we soon will learn much about: “Mason and Dixon, and all the McCleans, Darby and Cope, […] old Mr. Barnes and young Tom Hynes” (7). For, Reverend Cherrycoke was on the trail with Mason and Dixon and spent much time with them before they ever went to America; so, if anyone knows their story, it would be him. He wants to tell of these names, though ponders on whatever happened to them after Mason and Dixon left America, shortly before the Revolutionary War began. He believes that many of them likely lost their lives in this war, just as Mason has now lost his — Mason being the funeral he had come to town to see, dead a couple months earlier in October of 1786, having outlived Dixon by a bit over seven years.

The story begins with a few musings.2 Cherrycoke thinks on the line that they all had devised — that is, what is now known as the Mason-Dixon Line, an East-West border separating the southern edge of Pennsylvania from the Northern edge of Maryland, and a North-South line separating the western edge of Delaware from the eastern edge of Maryland. Just as many things begin, this line was originally “drawn as a result of a property dispute between the Penn family (of Pennsylvania) and the Calvert family (of Maryland)” (Biebel, 13).3 As Elite power structures will do, They will take disputes and render them beneficial to Themselves. So, while this line’s original purpose was “‘nullified by the War for Independence,’” (8) it is not as if the line were erased from history. It remained as the dividing line between America’s North and South, between slave-states and the purportedly free-states, between a Union and a Confederacy. Therefore, while the line’s original intent was not a fabrication of history, all things funded by those in power have a duplicity. They knew that it could hold many other purposes within itself.

Cherrycoke ends his musings and begins his story with a ‘parsonical Disguise’ — the imitation of a moralizing cleric-like figure — thus furthering the notion of his style of storytelling, both saccharine and moralistic. Though, quite often, moralistic tales miss the forest for the trees (both in the platitudinal sense and that of the natural destruction necessitated by the line’s formation). Even better, Cherrycoke begins with quite the hook: “‘It begins with a Hanging.’ ‘Excellent!’ cry the Twins” (8).

Ah, it is not a true hanging, but a metaphorical one. Cherrycoke waxes on about his nontraditional nature as a Reverend, calling Wesley and Whitefield to mind, two ministers who disagreed over the topic of ‘predestination’ (Biebel, 13-14) — the fact that certain people have already been predestined by God to be chosen for heaven, while others have been deemed already sinful, with no chance to be saved. This calls to mind two terms we should be familiar with in Gravity’s Rainbow, the Preterite and Elect — or who those familiar with a certain philosopher should know as the Proletariat and Bourgeoisie. Why should some be destined for greatness — heaven, wealth, eternal life — while others are destined to be stepped upon by their ‘superiors’ — hell, purgatory, poverty, peasanty, slavery, death. So perhaps, while Cherrycoke may be telling a highly saccharine version of this coming story, he is well aware of the many implications it will hold. John Wade LeSpark wants him to somehow indoctrinate his children in the light of American History and Greatness, and while the Reverend isn’t wholly exempt from blame, he may be using this as an opportunity to enlighten them, just as Pynchon is attempting to do the same to us.

Another character is introduced, Uncle Ives, or Ives LeSpark, brother of our Patriarch, John Wade LeSpark. Thus, while he is associated by blood with our American Miliary Industrial man, he is not at that same level of power. Is he us? Or those who are simply attempting to survive by benefitting off of those industries? Or is he complicit as well? Either way, he is curious as to why Cherrycoke was nailed with specific criminal charges. Apparently, backing up our evidence of Cherrycoke being privy to Preterite/Elect dynamics, he was clapped in ‘the Tower’ for posting up anonymous messages revealing crimes “committed by the Stronger against the Weaker” (9) — many of these crimes, such as ‘eviction’ and ‘Activities of the Military,’ still being perpetrated both in Pynchon’s later novels and our real contemporary world. And because of this, Cherrycoke was arrested, deemed insane, and realized that his “name had never been [his] own,— rather belonging, all this time, to the Authorities” (10). Being deemed insane would be highly beneficial to those in power,4 rendering the class-conscious ‘ramblings’ of a Man-of-God to be nothing but the misfiring of some neural lobe. His penance for his crime: exile on a sea voyage on which he would meet and accompany Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon.

With the page break and with the words “Tho’ my Inclination had been to go out aboard an East Indiaman” (10) we lose the quotation marks of Cherrycoke’s narrative. Biebel states that this will lead “Cherrycoke’s presence as a storyteller [to become] more hidden or ambiguous […] and that will provide Pynchon with the opportunity to complicate his narrative and foreground questions of history and storytelling” (Biebel, 14). In other words, not only is this book going to be a revelation of the implications of historical actions taken by the Elite in the time of Mason and Dixon, but it will be an analysis on how history itself is written. Who are we to trust? Those who experienced history and told its story to their children? those who had the privilege to write history down in text? the courts of kings and queens? the unreliable journals of those who lived through it? We will see this story and history told through a number of these perspectives. It is always important to ask: who do we believe?

The Reverend’s exile was purposefully set to most inconvenience him, putting him aboard a frigate known as the Seahorse manned by Captain Smith. Upon complaint, he was reprimanded by his superior, the reprimand thus requiring him to fake his subservience to this entity. But either way, subservient or not, he is aboard the Seahorse, headed East. He knows that Westward travel has always implicated death, destruction, colonization, and the like. So, what he hopes is that this trip Eastward will provide him with something like those spiritual Eastward travels told of in many a tale. Yet, of course, the vessel which travels to the east is loaded up with “thirty-four guns’ worth of Disaster” (11). Perhaps it’s not the direction which implicates the outcome, but the objective. We rarely see a ship loaded with white men and weaponry and think anything but, ‘oh shit, here they go again.’

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 2

Next week’s chapter is the shortest in the novel, so it will be a quick post, but the week after that will begin the story-proper!

For example, many of Pynchon’s novels take place during the Cold War in America when the average American would not be experiencing the true horrors of the world brought to their front door. The only two of Pynchon’s novels which take place during explicit historical turning points as opposed to the more subtle ones would be Gravity’s Rainbow and Bleeding Edge.

When the story proper begins — kind of in Chapter 2 and full-force in Chapter 3 — we will see Mason and Dixon’s work and acquaintanceship grow well before they ever travel, or even realize they ever will travel, to America. But the Reverend’s musings have to do with America so to set the stage.

Biebel, Brett. A Mason & Dixon Companion. The University of Georgia Press, 2024.

Note 1: Brett Biebel has given me permission to use his wonderful companion throughout my analysis of Mason & Dixon. So a massive thanks to him. His work was incredibly enlightening and helped me fully form my thoughts on this great novel. I would also like to say that while I have read a decent amount of Pynchon scholarship, very little of it ever touches on the major themes that I’m interested in drawing out. Biebel’s work breaks that trend. He is fully interested in what I think Pynchon truly intended to elucidate in his works. So I highly recommend you get this companion to help in your own read as well, because there is plenty in there that you won’t find in my analysis. I’ll mostly be using his work for the historical aspects of the novel since I am not all that familiar with the history of the era, though admittedly, some of his thematic analyses were quite revelatory as well so I will cite those when they were not of my own devising.

Note 2: When citing Pynchon’s novel, I will only cite the page number (or the chapter if I’m referencing a previous chapter of the novel that I already wrote about), but when referencing the companion, I will reference the author as I did above.

A few characters will feign insanity for similar reasons, and a major discussion of this will occur in 1.6.

Cherrycoke and his reportage reminded me of William Slothrop, who similarly offended the authorities with his book "On Preterition."

Excited to be starting this one! It's interesting how the prose is still recognizably Pynchon despite the period trappings. Also impressive how I went from being kind of annoyed by said trappings to basically fully adjusted in the span of a dozen pages.