Gravity's Rainbow - Part 3 - Chapter 24.2: Second Thoughts and Final Decisions

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 3 - Chapter 24.2: Pirate's Hesitance, Katje and Pirate Speak, How I Came to Love the People, Katje and Pirate and the People Dance

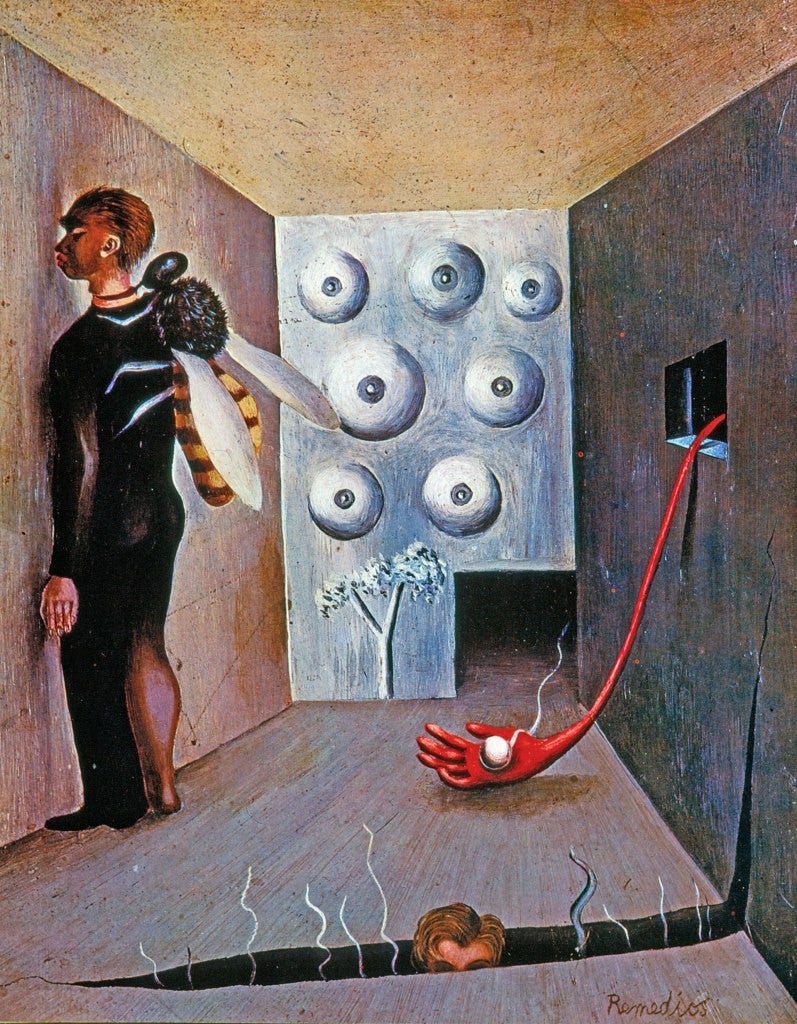

Still in his dream, slowly being convinced that he must help form this apparent revolutionary counterforce, Pirate recalls a film with an “approximately human, terribly pale, writhing [figure] behind the crumbled remains of plate glass” (542). It is a one-time soldier who worked for an espionage unit. Those people who worked for intelligence agencies, who have seen things that are not allowed to be spoken of, cannot lead normal lives afterward, and so he is here, symbolically diseased — scratching at the ‘sores’ that plague him — having attempted to live a normal life after being a partisan in the atrocities that were committed.

Pirate, seeing this, fears that it could one day be him — that given his own participation and subsequent desire for a normal life, he too would not be allowed freedom from suffering: mental or physical. But the issue is that in light of his coming desire to help fuel a counterforce, he also realizes that “‘No one has ever left the Firm alive, no one in history — and no one ever will’” (543). Therefore, he learns via a few hints from the cast within his dream that in order to conduct this necessary but almost certainly suicidal plot, he would need to play ‘double agent’ — as both an insider within the intelligence agency and a Preterite rising to bring said agency, and, as one would hope, the entire system, down.

This decision does not come lightly, and we can see Pirate’s struggle with the thought of it when, having “never cried in public like this before,” (544) he begins thinking of everything he could lose in the process. The fight would lead to him never again seeing the people he has met and loved, the things he has yet to see, even Scorpia Mossmoon, the married woman who Pirate was in love with and who the White Visitation used to both control his desires and ensure his obedience (1.5 & 1.11). He pictured those who he would have to betray: co-workers who, while they were committing the same acts he once was and were not having a change of heart, were still his friends. He pictured other past lovers and dead, living, or dying relatives, some of whom may be targets once he is found out or who he may simply never see again. He pictured the future which he would not see, the history which he would not bear witness to. It is that sense of Elect immortality that has been built up within him which gives him pause. Yes, he knows his name will be, maybe even already is, on a list, just like very soon other revolutionary men’s names will be on lists: MLK, Malcolm X, Salvadore Allende, Patrice Lumumba. But if he accepted the collective form of immortality, if he let go of the shame and guilt of committing the wrongs that have already passed, let go of the fear of leaving those whom he loves behind, then the path forward is obvious — necessary, even.

Katje — a dream Katje, though it is likely that the real Katje is going through a similar mental turmoil like Pirate — walks in. She wonders if here in Hell, after the death that may soon be coming for the both of them, the dead who attribute their death to her would haunt her — another fear of what may come. Pirate initially misinterprets this as a familial death, bringing Frans van der Groov back to mind momentarily, the symbol and allegory of ruthless and mindless genocide — that type of genocide being the same thing he and Katje are now contemplating fighting against.

But she is not really here to beg him to save her, as Stephen Dodson-Truck states: “‘She doesn’t want you to fight for her’” (545). Right now, they are both here, standing in utter terror of what lies ahead of them — at the possibility of accidental betrayal, or a betrayal that stems from fear or torture or whatever else They may have planned. Yet Katje reminds him, these are possibilities — things that have not yet come to pass, things we could pledge against. There is not use or logic in bearing one’s decision on these mere possibilities when the stakes of inaction are so high. Pirate counters her: he says that he would recommit old sins if it meant success, so why should we assume the possibility of betrayal is just that: a possibility, and not an inevitability. Of course, she does not buy into these excuses or at least does not find them as means of justification. However, she does find his fear and his thought process intriguing, humanizing even, going as far as calling him, a little jokingly, a ‘philosopher.’

Katje then compares Pirate’s situation to her brother, Louis Borgesius, stating that Pirate’s psychological fears and psychology in general may stem, like her brother’s did, from “‘always being in motion’” (546). He had left home at eighteen, constantly on the move, loitering with youths, drinking excessively at too young an age, even going as far as joining the Rexists, a fascist organization started by Léon Degrelle which proposed heavily right-wing policy and a supremacy of the Catholic Church, thus leading them to openly welcome the Nazi party. Similarly, one could argue that Pirate’s inability to stop moving led him to unknowingly step into a realm of evil and work for Them, just as Louis did. So much ceaseless information and action could blind somebody. Or as Katje says: “‘We did everything ourselves’” (546). Meaning, our sins could be our fault entirely, but it is also because this movement, however evil, led us to grasp the one thing that could give meaning to our unrelenting life. We must, therefore, swallow our shame — come to terms with what we’ve all helped propagate.

They hold each other, walking toward the balcony, and ask what the other sees in the outside world of Hell: the one that Pirate viewed as an office block and that the previous girl saw as a garden. Katje sees it entirely barren, which could be a sign of foreboding, but which also gives the possibility of rebuilding and rebirth.

On the balcony, they see the People walk in the streets below them — the same People, the Preterite, who they want to save. A perverse, hellish voice chants out a piece called How I Came to Love the People. It is Their version of what love is: a form of control as always, but also one that makes the person seem like a collector, someone who would only ever save a person who loved them back. The voice makes the unspoken argument that ‘if you won’t give yourself to me, if you won’t degrade yourself in the obscenest manners for my pleasure, why would I save you?’ They do not see value in one who will not do as such. But Katje knows, “‘the People will never love you […] or me,’” (547) and why should that matter? Why would a person only fight for those that one loves. If one sees these atrocities occurring on a worldwide scale, is it moral or just to stop your fight once you have saved, say, your family, or once you have reached the border of your country’s end? Is the person on one side of a fence less valuable, less human, than another?

This seems to be the question that helps Pirate decide his future. He looks above him, through all the layers of Hell or whatever land they may really be residing in at this moment, seeing the massive weight of human life that rests on the shoulders not necessarily of only him, but of all those like him who are willing and able to push the fight forward. Seeing this realization in his eyes, Katje places her head against his chest. The light in the city begins fading away; the People are scared that this could be the last cycle of day they ever see if there is not someone willing to fight for them. But for now, as they wait to see if one takes up that mantle, an orchestra, somewhere off in the background, begins to play music. The lyrics call out the experience of the People: walking city streets innumerable times, having lost or left friends behind, having desired to hold each other and spend some time with loved ones before the world comes to an end, even to simply dance the evil of the world away. So that is what Katje and Pirate upon their balcony, and the People down in the streets, do. They dance. And as Pirate and Katje dance, they dissolve back into the mass down below; just because the two may be leading this revolution forward, they are no better than the People themselves. For remember, the collective immortality of the Preterite relies on that fact that we live and fight for each other, not simply, like the Elites, for ourselves and our elevation. This is the one thing They would never understand: why would one fight for someone who provides them no value? who they do not know on the most intimate level? who does not benefit them economically or politically in any manner? It is because They do not know love — how to stand in the place of others, how to strive, simply, for peace, compassion, kindness.

Up Next: Part 3, Chapter 25

Thanks so much for these essays. I put down GR a couple of months ago (for the second time) as I was overwhelmed and a bit lost. You’ve got me back on course! We’re nearly home - let’s go Slothrop!

This episode seems similar to Pierre finding the Free Masons in War and Peace. Where he finds spirituality through serving others and removing class structure (at least symbolically) by freeing his serfs.