Gravity's Rainbow - Part 1 - Chapter 16.2: Humanity's Lament

Analysis of Gravity's Rainbow, Part 1 - Chapter 16.2: The War's Evensong

Christmas day. Roger and Jessica are together again. They observe an assortment of men and women enter a church and Jessica recalls that yes, in fact we did once have times like this. Though, times like this are long past — times where peace lay over their city like blankets of snow, where men and women gathered together en masse to hear a song, an evensong. And Roger, pessimistic Roger, himself surprised at the scene. . . well even he wants to go in to watch.

Jessica, who seems to have little memory of the before-times, now remembers her childhood, the only moments where this type of scene was the norm. Thoughts of childhood bring to mind the children not present in the scene — those off at home or those who have passed — and she contemplates easing the fears of their mortality.

The band is made up of a similarly odd number of members, led by none other than a Jamaican corporal, brought over from his hometown in Kingston for whatever needs the West may have had in mind for him. To Them, he is just another import. Though at least here, looking past whatever circumstances and trials he may have gone through, he too has his moment of peace. Other things are melding: “the Latin, the German? in an English church?” (129), and sung by a man from Kingston, nonetheless. This is all just an outcome of our imperial world — taking a bit of everything and mashing it all together until one could not even begin to decipher the meaning or its origin. Though again, while this in some instances may call to mind the horrors of the modern world, here we see the beauty of what it can create if things were allowed to settle.

As Jessica begins to see the change in Roger, The War’s Evensong begins – an amalgamation of each of these groups, calling across the continent, creating with their voice a series of images and metaphors; for, what we hear is not a song, but every pain and vision of the singers and listeners. These voices call out the entire lament:

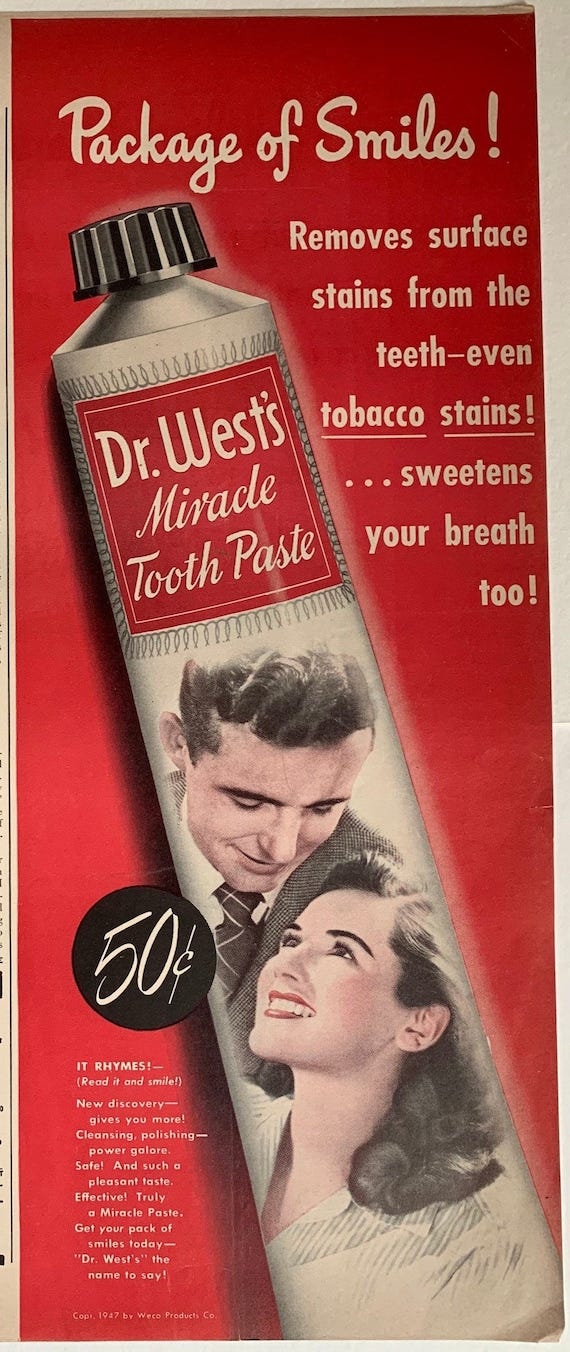

First, connections are made. Toothpaste, such a simple and essential product, has found itself being used by the war. It has always been a solace for those at days end, or something to complain about for those much younger. That is what it was though. The war has changed it from a product of hygiene to one of fuel. It (being stored in tin and lead tubes back during WWII) is used and then melted down to bring these base metals back into the war itself. A simple connection until one realizes that this is a single product. These products all have a trajectory, being bought, sold, advertised, and then by whatever the set path is, working its way by some obscured means until it provides fuel for the war. Each person thus supports the war in some way. There is no way around this as it is all built so that even with the discovery of one pathway — even if one were to fully cut off that branch — there are dozens of others ready to open up, or that are already working full force as well. And humanity, too, has been commodified; we have become fuel — used over and over, slaughtered in place of someone higher and more important, used as scapegoats to protect the elite.

But what are these connections to the singers and the listeners. They exist and they fuel this suffering but suffering and loss are the true motifs of the song. Love and celebration have been put to a standstill, wedding dresses grow yellowed in shop windows, lost souls wander the city streets, children’s toys blacken from soot, a fear lingers in everyone’s mind that a rocket may take them at any moment unannounced, people reminisce about a time where daily little fusses took precedence over conversations of life and death. All they want is to treat their children to the life they had envisioned for them, but “the War has shunted them, earthed them, those heedless destroying signalings of love” (133). Parents and grandparents stand vigil over their children’s presents during Christmastime, though this year — these years, really — instead of pondering the joy they will bring to them, they sit there, asking, “What Is Emphysema? What Is A Heart Attack?” (133).

If “The War needs coal,” we will provide it, and if “The War needs electricity,” (133) they will find a way for us to provide that as well. For even the minute hand is tethered to Their needs. The branching paths twist to the point where we cannot see their end or beginning, cannot see which facets they connect with, cannot see what binds us to Them. Because of these needs and these tethers, humanity has lost nature to the war. Our beaches are riddled and unusable; birds drop dead out of the skies. Because of these tethers, humanity has lost every iota of individuality we had to the war. Our face and identity stolen by government cameras; organs toyed with. And everyone is in on it. The tethers branch out further to doctors whom you know and suspect, to names you’ve never heard, to names that have no place in your life, and you ask: how could they be involved in my life. Well, they are. They’re over there “wondering should they, maybe, give everybody a number” (135).

So, we come back to the church. The song is being sung by every lost and pained soul. It is humanity’s lament — art that could only ever have been created by a soul in torment, a song that should never have had to be written.

Tough one to write about because it’s more of a piece that should just be read. It will make sense to you on its own. (And plus, without any through line, it’s damn hard to write about as well…) But I hope I did some justice to the major and minor themes running through this piece. It is perhaps one of the most beautiful passages in the English language.

Up Next: Part 1, Chapter 18

I'm answering a little late but I have been enjoying reading along with these for my read-through and I guess this is as good a time as any to ask: are 'They' real? Do 'They' actually exist or is it a deliberately nebulous construct the characters of the novel can blame all of the world's ills on without needing to take a more nuanced look at the actual society that leads to all of their problems? Problems which may be at least to some extent the characters' own personal issues rather than conspiracies? I recall last the post on 16.1 with Jessica and Roger. Perhaps Roger and Jessica's falling away from each other is not the result of some grand dehumanising capitalist force, and is just the much more simple fact that sexual compatibility and yes, even passionate love, are not sufficient for a long term healthy relationship where you also need the friendship and simple trust that Jessica seems to have with Beaver.

The rhetorical framing of those questions probably indicates where I stand, but I'm not 100% confident I'm necessarily right in that assumption. The fact that the book literally always used capital T 'They' which feels like a caricature of paranoid conspiracy theory types sort of made me feel that Pynchon was hinting at that. I ask this here because the way your analyses really confront that feeling in the book of oppressive systems so vast as to be insurmountable yet so ingrained as to be barely perceptible just ticked me off to these considerations.

With how much the Counterforce fail at the end of the book, is Pynchon critiquing the paranoid mentality that reduces the hyper-complex and increasingly post-human systems of our world to some malicious human deliberation rather than admitting it's way more complicated than that? I'm pretty much spitballing here lol.